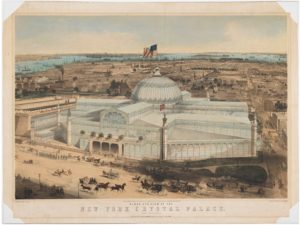

An article published in the June 17, 1854 edition of The Circular reviews a recent choral and orchestral performance at New York City’s Crystal Palace 1, an exhibition venue built to rival London’s own Crystal Palace. The Crystal Palace opened in 1853, but was soon closed in 1854 due to financial constraints. Just four years later in 1854, the building and all its contents burned down.2

John Bachman, Birds Eye View of the New York Crystal Palace and Environs, 1853. Hand-colored lithograph. The Museum of the City of New York, 29. 100.2387. Image and caption from the Bard Graduate Center’s Exhibition: “New York Crystal Palace 1853.”

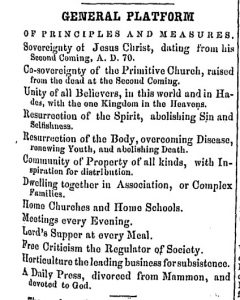

The Circular, a community-written and edited newspaper, makes sure to emphasize its values to its readers. The front page of this edition features the newspaper’s “fundamental principles,” “leading topics,” and “general platform,” all emphasizing a devotion to the Christian faith and the institution of Communism and Socialism.

An excerpt from this edition of The Circular‘s front page, detailing their mission and values. “Music in the Crystal Palace.” Circular (1851-1870), Jun 17, 1854. https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/music-crystal-palace/docview/137665576/se-2.

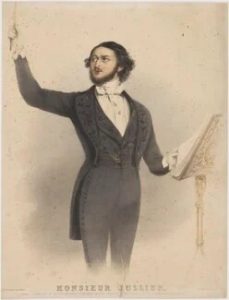

Later on, the publication features a positive review of a concert performed by the “Musical Congress,” under the direction of Louis-Antoine Jullien. The review details the pieces performed, such as Handel’s Messiah, and, in an interesting bit of foreshadowing, an original composition by M. Jullien entitled, The Fireman’s Quadrille. According to the review, Jullien’s piece tells a story of a fire and the firefighters’ heroism, “expressing in music the silence of the night, the alarm, the rush of engines, the crackling of the fire, crash and falling of buildings, the final victory of the firemen.” The author seems entranced by M. Jullien, even calling his baton a “wand,” implying a sense of magic to his conducting. Read the sheet music for The Fireman’s Quadrille here.3

A colored lithograph of Monsieur Louis-Antoine Jullien by Edward Morton, after Alfred Edward Chalon. Edward Morton, “Louis Antoine Jullien,” digital image, National Portrait Gallery, 1840s, accessed October 3, 2022, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/use-this-image/?mkey=mw195155.

But perhaps the most interesting part is the author’s thoughts on Christian Communism as it relates to the performance. They speak of the performance as a “splendid exhibition of unity, and of difference in unity.” Their remarks center around one specific idea, that each musician is bound to a sense of togetherness, in that each part of the music is essential to creating the whole sound. The author reflects that thousands of people attended this concert, each presumably leaving the venue with different thoughts on the music they just heard. This speaks to the connection of identity in music, as everyone who hears a piece of music may draw different personal conclusions and connections. One person, the author, may think from the lens of Christian Communism, but another spectator may be connecting the music to the Black experience, or listening for the French influences in Jullien’s writing. Whatever the case, this author clearly understands the significance of personal connection to music.

1“Music in the Crystal Palace.” Circular (1851-1870), Jun 17, 1854. https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/music-crystal-palace/docview/137665576/se-2.

2 Henry Raine, “What was the New York Crystal Palace, and where was it located?,” New York Historical Society Museum and Library, January 12, 2012, video, 1:00, https://www.nyhistory.org/community/new-yorks-crystal-palace

3 Music Division, The New York Public Library. “The fireman’s quadrille” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed October 4, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e2-cf65-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99