In his paper “MacDowell’s Vanishing Indians,” Dr. Daniel Blim writes that the “Indianist” movement of using Native American inspiration for American music owes its success largely to the composer Edward MacDowell, and especially to his Indian Suite, premiered in 1896. Blim connects this to the “vanishing Indian” trope: “the Indian as a cultural figure . . . began to ‘vanish,’ and no longer a threat, could be reappropriated in the national imagination as a nostalgic figure rather than a living oppositional force.” He discusses MacDowell’s Westernization of Native American music as one way in which it aligns with this trope. Regarding MacDowell’s piece “From an Indian Lodge,” Blim writes, “the subject of this work is not Native America, but a reenactment, subtly Westernized.”1

Reviews of the Indian Suite support this view, showing a strong alignment with the “vanishing Indian” trope and praising MacDowell’s Westernization of Native American music. Blim uses the Indian Suite as an example of MacDowell’s music before it reflected the shift to the “vanishing Indian” view, still depicting Native Americans as a “living oppositional force.” However, the following two reviews, though approaching the Indian Suite from opposite directions, both project the “vanishing Indian” trope onto the piece.

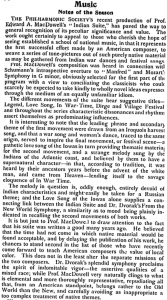

In 1898, the magazine The Critic published a review (right) praising MacDowell’s ability to “weave a series of tone-pictures out of . . . purely native material.” It contrasts his suite with Dvořák’s ninth symphony, stating that MacDowell “clings to what is elemental and more thoroughly representative, . . . carefully avoiding as inappropriate a too complex treatment of native themes.”2 Rather than seeing Native Americans as a living opposition still in need of Westernization, The Critic praises MacDowell for getting to the core of what is Native American, showing the extent to which their opposition had been replaced by an opportunity for inspiration.

In 1898, the magazine The Critic published a review (right) praising MacDowell’s ability to “weave a series of tone-pictures out of . . . purely native material.” It contrasts his suite with Dvořák’s ninth symphony, stating that MacDowell “clings to what is elemental and more thoroughly representative, . . . carefully avoiding as inappropriate a too complex treatment of native themes.”2 Rather than seeing Native Americans as a living opposition still in need of Westernization, The Critic praises MacDowell for getting to the core of what is Native American, showing the extent to which their opposition had been replaced by an opportunity for inspiration.

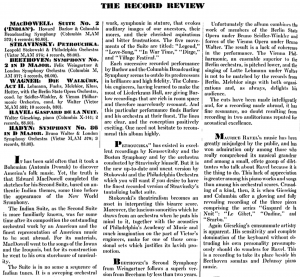

In 1939, 41 years later, the magazine Forum and Century also published a review (left) praising the Indian Suite, but comparing it favorably with Dvořák’s symphony: “The Suite is in no sense a sequence of Indian tunes. It is a sweeping orchestral work, symphonic in nature, that evokes auditory images of our ancestors, their mores, and their cherished aspirations and bitter frustrations.”3 For Forum and Century, rather than Westernization being an obstacle, it allows the Native American to be more effectively appropriated, so much so that they are now “our ancestors,” and the music’s frustration that Blim associates with their oppositional position now reflects the “bitter frustrations” of the Native Americans themselves.

In 1939, 41 years later, the magazine Forum and Century also published a review (left) praising the Indian Suite, but comparing it favorably with Dvořák’s symphony: “The Suite is in no sense a sequence of Indian tunes. It is a sweeping orchestral work, symphonic in nature, that evokes auditory images of our ancestors, their mores, and their cherished aspirations and bitter frustrations.”3 For Forum and Century, rather than Westernization being an obstacle, it allows the Native American to be more effectively appropriated, so much so that they are now “our ancestors,” and the music’s frustration that Blim associates with their oppositional position now reflects the “bitter frustrations” of the Native Americans themselves.

From only two years after the premier through the following several decades, MacDowell’s Indian Suite was fully enveloped by the trope of the “vanishing Indian.” Though approaching the piece from opposite directions, both reviews celebrate MacDowell’s synthesis of Native American music. They do not make Blim’s differentiation between the suite and pieces that more explicitly align with this trope. Rather, due to the strength of the national shift spurred by MacDowell himself, they project onto this piece the concept that the Native American has vanished and transformed into fodder for American music.

1. Blim, Daniel. “MacDowell’s Vanishing Indians.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society and the Society for Music Theory, Vancouver, BC, November 2016.

2. “Music: Notes of the Season.” The Critic: A Weekly Review of Literature and the Arts (1886-1898), Feb 05, 1898, 97, https://search.proquest.com/docview/124892533?accountid=351.

3. ARTHUR, WALLACE HEPNER. “THE RECORD REVIEW.” Forum and Century (1930-1940), 11, 1939, 1, https://search.proquest.com/docview/90883079?accountid=351.

“Edward MacDowell, Suite No 2, Indian, Op 48.” YouTube video, 36:24, posted by

Gunnar Frederikson, Feb 28, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QUDiGsjKS_k.

“Woodland Sketches, Op. 51: No. 5. From an Indian Lodge.” YouTube video, 2:48, posted by Alexandra Oehler – Topic, Jan 30, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c0oeP9V27C0.