From pop sensations Bruno Mars to Iggy Azalea to old school entertainers like Elsie Janis, musical cultural appropriation has always been and is still a problem to many people. Is music appropriation a bad thing? Here is some background to understanding why musical cultural appropriation is a problem.

Cultural Appropriation

First, before we get to it, we need to understand what “appropriation” means. According to TheFreeDictionary.com the definition of music appropriation is: “the use of borrowed elements (aspects or techniques) in the creation of a new piece,” (TheFreeDictionary.com).

Now, appropriation of music styles in itself is not bad. However, once those music styles are being re-interpreted by people who didn’t originally create that particular genre or song style, we start to find problems. This is called “Cultural Appropriation”. According to The Free Dictionary, “Cultural appropriation is the adoption or use of elements of one culture by members of another culture.[1] Cultural appropriation may be perceived[2] as controversial, even harmful, notably when the cultural property of a minority group is used by members of the dominant culture without the consent of the members of the originating culture; this is seen as misappropriation and a violation of intellectual property rights” (TheFreeDictionary.com).

An example of cultural appropriation is when someone who is not Mexican throws on a Charro suit as a costume for Halloween.

Mexican Cultural Appropriation

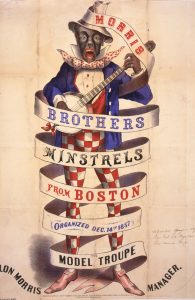

It is completely misrepresenting its origins. Cultural appropriation in music has been an issue in the Western world, especially in the United States. The reason is most, if not, all music that is “American” is originally black music. Most jazz, blues, ragtime, hip-hop, country, spirituals, and other songs we have discussed in class have found their origins in African-American culture.

Today, artists such as Bruno Mars and Iggy Azalea are being criticized for creating music in genres that originated from black musicians. Even after Bruno acknowledged his influences at the 2018 Grammy’s for example,

[Bruno Mars Acknowledges His Influences in 2018 Grammys]

an article was written about his role as a racially ambiguous artist in today’s music industry. Even Seren Sensei posted a video on Twitter defending her argument that Bruno Mars is using his racial ambiguity to further his credit in creating black music.

[Seren Sensei]

However, this issue is a bit more complex than it seems. To understand why, we must allude back to the cultural music appropriation of black music by white artists in the early 20th century United States.

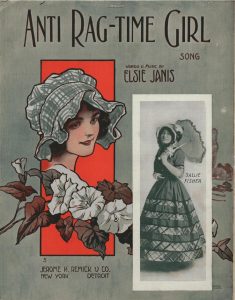

[Elsie Janis – Anti Rag-Time Girl (Audio)]

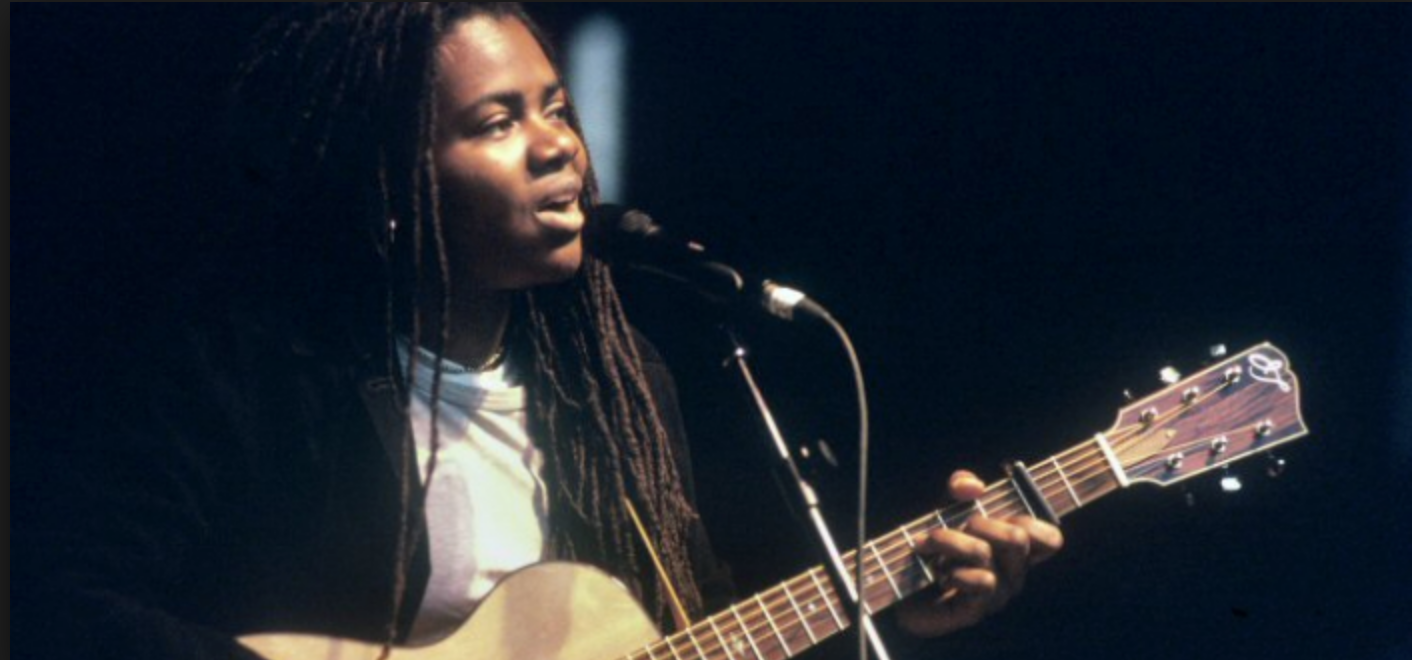

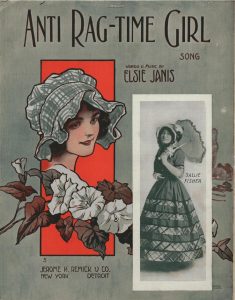

2nd: Elsie Bierbower, aka: “Elsie Janis” was a singer, songwriter, actress and screenwriter from Columbus, Ohio.  She moved to Los Angeles to live her dreams in the entertainment industry, and travelled around the world performing for vaudeville, Broadway and Hollywood. She was immortalized by her nickname, “the sweetheart of the AEF” when she would entertain the troops during World War I.

She moved to Los Angeles to live her dreams in the entertainment industry, and travelled around the world performing for vaudeville, Broadway and Hollywood. She was immortalized by her nickname, “the sweetheart of the AEF” when she would entertain the troops during World War I.

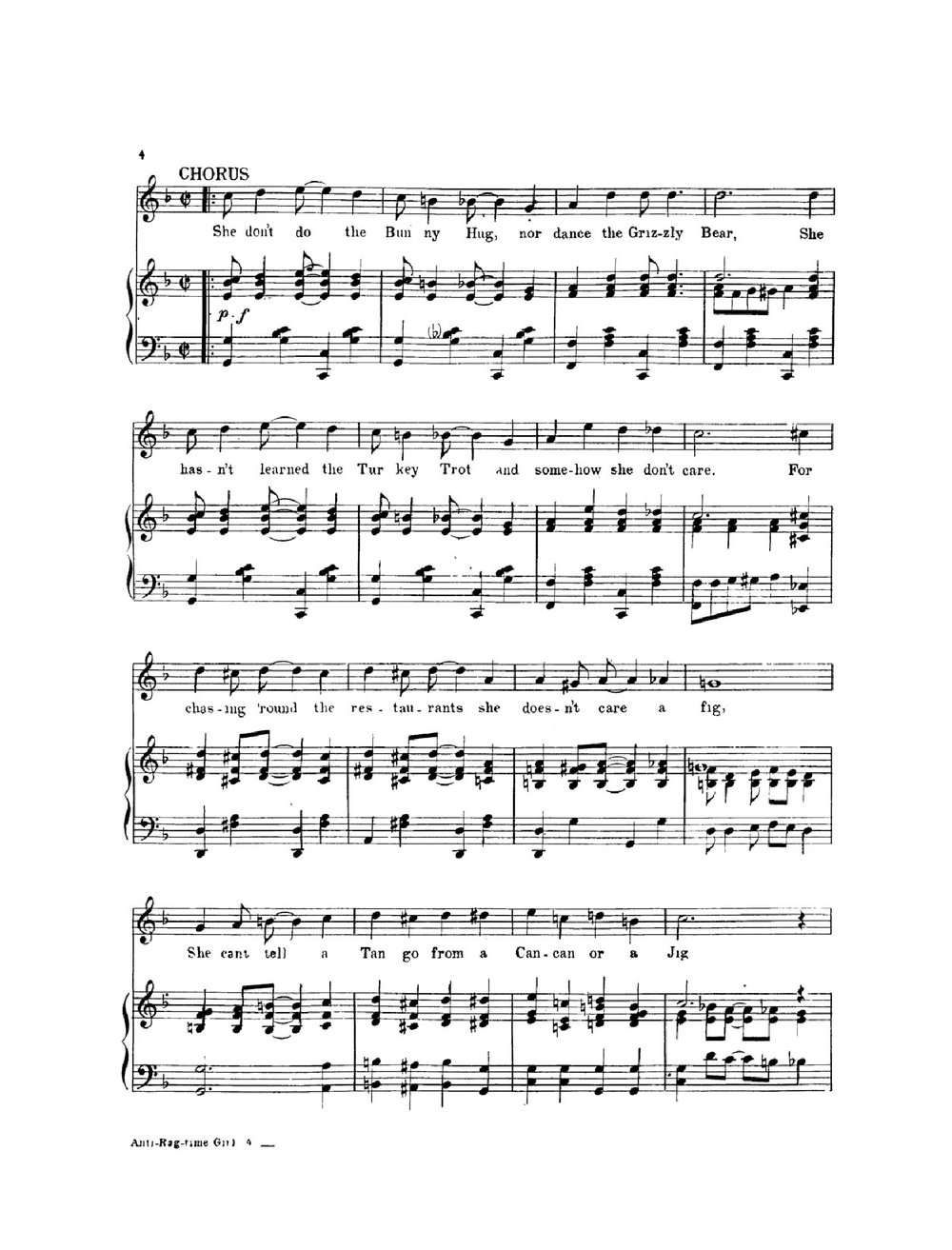

Elsie Janis – Anti-Ragtime Girl Sheet Music

Elsie Janis could be described as a someone who made it in Hollywood. She was very famous in her time. However, as with everything that seems to good to be true, Elsie utilized ragtime, an African-American genre, to write her 1913 song “Anti-Ragtime Girl”. By 1913, Ragtime was in its prime as a popular American genre, similar to how hip-hop is dominant in mainstream culture today. It is clear that she uses ragtime to create this piece. Are her actions considered cultural appropriation? Yes and no. Yes, because she did not invent ragtime music, and it is clear that she is living lavishly for herself based off the income of her music’s success. Some may argue that it is not moral for one to use another’s culture to re-interpret in another perspective. It is still very complicated.

That leaves us with today. Eminem, Iggy Azalea, Bruno Mars, and Macklemore have all won Grammys for their success in performing music that is arguably black music. However, differences in opinion leaves us with an open-ended question: Where does the line between creating original art and committing cultural appropriation sit?

Sources:

Collins English Dictionary – Complete and Unabridged, 12th Edition 2014. S.v. “appropriation.” Retrieved March 19 2018 from https://www.thefreedictionary.com/appropriation

Harriot, Michael. “The Bruno Mars Controversy Proves People Don’t Understand Cultural Appropriation.” The Grapevine. Retrieved March 19 2018 from https://thegrapevine.theroot.com/the-bruno-mars-controversy-proves-people-don-t-understa-1823709412

Janis, Elsie. “Anti Rag-Time Girl.” Oregon Digital. Retrived March 19 2018 from https://oregondigital.org/catalog/oregondigital:w66343646#page/1/mode/1up

Sheet Music Singer. “Anti-Ragtime Girl (1913).” YouTube. Retrieved March 19 2018 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=anQzoJQZerk

Wikipedia.org. S.v. “Appropriation (music).” Retrieved March 19 2018 from https://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/Appropriation+(music)