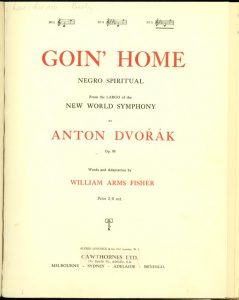

While scrolling through the sheet music consortium, I stumbled across a digitized piece of music of which I have a physical copy in my own personal library, “Goin’ Home,” an adaptation by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

by William Arms Fisher of Anton Dvořák’s New World Symphony (No. 9, mvt II Largo, specifically). Personally, I love the symphony and have enjoyed listening to it for many years, but I can’t help but wonder now about the complicated philosophies of Dvořák and this adaptation of his work which place the work not just as a well-known music history class example to memorize, but a work that has juxtaposed good intention with possible misguided ideology.

The sheet music I found includes a detailed account of Dvořák’s intention behind the New World Symphony and the melody on which this vocal piece is based. This description, shown to the left, describes Dvořáks fascination with the native people of the US. In his own desire to see his home, he attempted to fully understand the Native American and black music traditions which showed the true roots of American culture.

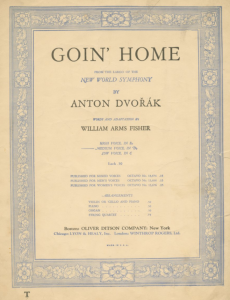

I think, overall, the attempt of this work to show Dvorak’s intent shows in the written dialect on the words “I’m Jes’ goin home” and “Gwine to roam no more.” Clearly, Fisher’s adaptation attempts to look to Dvořák’s attempts to draw on black folk music. The music does say that the singer may omit the dialect, which shows that people of all backgrounds were encouraged to sing this music. We also know from the forward of this piece pictured above that Dvorak, while attempting to make an example of true American music, also drew on his own experiences. The spirit of his work was meant to be applicable to many people. In “Goin’ Home,” Fisher develops Dvořák’s yearning for his own home into a universal message of hope for anyone searching for home.

I think, overall, the attempt of this work to show Dvorak’s intent shows in the written dialect on the words “I’m Jes’ goin home” and “Gwine to roam no more.” Clearly, Fisher’s adaptation attempts to look to Dvořák’s attempts to draw on black folk music. The music does say that the singer may omit the dialect, which shows that people of all backgrounds were encouraged to sing this music. We also know from the forward of this piece pictured above that Dvorak, while attempting to make an example of true American music, also drew on his own experiences. The spirit of his work was meant to be applicable to many people. In “Goin’ Home,” Fisher develops Dvořák’s yearning for his own home into a universal message of hope for anyone searching for home.

However, the message is pointedly not universal when it is directly associated with black folk music. Even more so, the white composer and arranger have not used an actual black folk tune but made one up – this causes confusion and leads people to believe that the song is originally a black folk tune. Instead of lifting up an already existing melody in the black folk tradition, Dvořák stereotyped his idealized version of folk music and missed an opportunity to showcase genuine, authentic folk music. While the attempt seemed earnest in its good intent, the execution remains slightly subpar.

We must also consider what it would have meant if he’d used a black folk melody. Would appropriating one have been much better? He was stuck between creating one on his own and using an existing one – both appropriation and creation would have contributed to the erasure of this culture in some form, though. As someone who was not part of the black folk tradition, it would have been impossible to find a way to authentically emulate these traditions without erasure. This brings up the question of whether or not he should have written this at all.

I hesitate to say he should not have. Whether that is simply because it is beautiful music or because there is some other argument that he contributed to American music in a way different than MacDowell (who contributed to a “vanishing Indians” idealogy), I cannot say.1 This piece, especially controversial given its dialect text, would be an excellent addition to our class exhibit, however. Since I own a personal copy, and we can give people a QR code that lets them access it online and peruse anytime, I think that it is an accessible source that many could use.

1 Daniel Blim, “MacDowell’s Vanishing Indians,” paper delivered at the annual meeting of the American Musicological Society, Vancouver, BC, November 4, 2016.