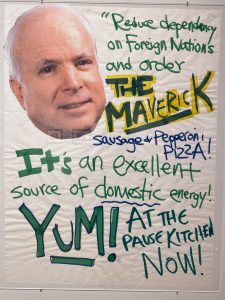

Likely created by a student artist in partnership with the Pause Kitchen at St. Olaf College in 2008, two posters advertise different pizza toppings representing the candidates of the 2008 presidential election, Barack Obama and John McCain. By incorporating the candidates in the advertisement in a silly manner, the posters aim to use comedy to lighten the political atmosphere of the time. What can this example of comedic relief tell us about the use of comedy in other forms of art, such as in the history of Black performance in America, and Black-face minstrelsy, and how comedy affects engagement in difficult conversations?

In the Flaten Art Museum’s (FAM) Fall 2024 exhibit, “Practicing Democracy,” there were many artifacts related to the civic engagement of Oles at St. Olaf throughout its 150 years as an institution. Displaying colored and black and white photos, videos, buttons, and descriptions of live and recorded performances at sports events, this exhibit covers a breadth of examples of civic engagement from former students. One display especially caught my eye – two posters hanging side by side with bright, bold colors and fonts, featuring giant, blown up faces of each candidate the faces of the 2008 presidential election, Obama and McCain, in the upper left hand corner of the poster. Whether or not the posters helped in boosting the sale of “The Barack” or “The Maverick”, the pizza orders the posters advertised, these posters most definitely caught the attention of students walking by the Pause Kitchen, not only because of the colors and funky font, but due to the sheer size of each poster, both posters likely being the size of a concert poster (about 24 by 36 inches). As one of my classmates stated while our American Music class took a tour around the FAM, the use of comedy likely helped to ease political tension “over a slice of pizza”, opening up discussion around the former presidential candidates and their policies of the time. Additionally, by including pineapple on “The Barack”, the posters also open up discussion on a widely controversial pizza topping. With a little silliness, the unknown artist of the posters probably hoped that students would be more open to approaching political conversations, paralleling political conversation to pizza topping preferences.

And what of comedy used and referenced in our class readings and listenings? There have been many times in which comedy or mockery has been featured in the music we have studied. Blackface minstrelsy is an example we studied, being a problematic art form that utilized mockery and stereotypical comedy to paint Black individuals and communities as an inferior race and group of people. Additionally, because theater performance was often limited to White male performers and actors, minstrelsy explored gender and sexuality, teetering between socially accepted and unaccepted ideas of gender, gender performance, and sexuality. By leveraging comedy and comedic relief, these forms of performance encouraged and perpetuated harmful ideologies of Black people, positing White audiences to rationalize the feeling of superiority.

The performance of minstrelsy was not solely limited to White male performers throughout it’s history — Black performers used blackface minstrelsy as an angle to perform in theater in front of White audiences. As Sullivan states in his article, “‘Shuffle Along’ and the Lost History of Black Performance in America,” “by mocking themselves, their own race, they were giving it up.” Because White audiences were uncomfortable with Black people showing up as they were on stage, and, in a sense, “claiming power” over White audience members, minstrelsy was a way for Black performers to ease their presence into theater.

In these instances, comedy isn’t used to break down walls to difficult conversation like in FAM’s display of “The Barack” and “The Maverick”, but is instead used to build a disconnect between White audiences and Black people. The comedy of minstrelsy made White audiences’ prejudiced perceptions of Black people more digestible, and later, caused White audiences’ perception of Black performers to be less threatening.