Black slave song was once a purely functional form of music that was described as “primitive” or “not inherently musical,” and the thought of it pervading American popular music once seemed impossible. However, after going through a metamorphosis of sorts, it changed into a form that appealed to the people of the United States. By undergoing this change, the songs had lost basically all semblance of their original function as a work song to an art song. Thus began the assimilation of black folk songs into American folk-songs.

As a result of black folk music being introduced to the American public, people wanted to capture the origins and nature of this new genre. Books were written chronicling and collecting black folk songs, among them Afro-American Folksongs, A Study in Racial and National Music by Henry Edward Krehbiel and On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs by Dorothy Scarborough. Although these books were invaluable as a source for the average person to learn more about black folk songs and accounts of their encounters with the people that taught the authors the songs, they were written by white people using standard musical notation that is not able to accurately portray how the songs would have actually been performed by the people that originally sung them.

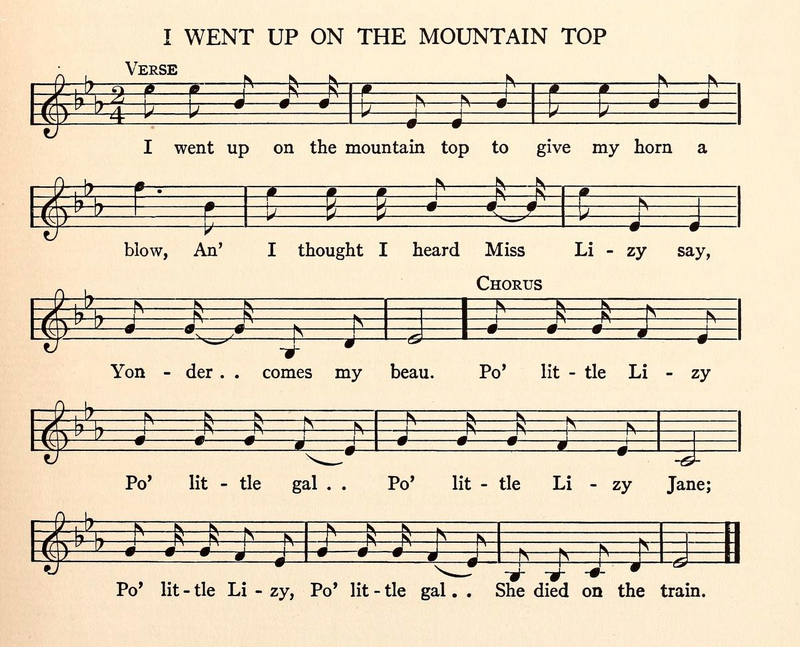

For example, take this transcription from Scarborough’s book of “I Went Up on the Mountain Top:”

The notes, rhythms, and words are present, but we have no idea how accurate this is. We can only assume how fast it went, how to pronounce the words, and the harmonies implied, if any. What results from this collection of songs is not an authentic depiction of black folk tunes, but “…a body of beautiful music. It has been neglected, distorted, made pretty, made tawdry, and now is being presented in various approaches to its native beauty.” [3] This issue of “beauty” became even more contentious when considering how to perform these songs:

Due to the vague nature of the transcriptions written by authors such as Krehbiel and Scarborough, the “correct” rendition was up to interpretation. However, it was agreed that that the expression of the text was far more important than the style in which a person sang. Hayes and Robeson are incomparable, but they both hearken back to the original spirituals and the idea of expression as beauty. Although the black slave song was once thought as the music of savages, it quickly became an integral part of American music and was not going away anytime soon.

1. 3. 4. Seldes, Gilbert. 1926. THE NEGRO’S SONGS. The Dial; a Semi – Monthly Journal of Literary Criticism, Discussion, and Information (1880-1929), 03, 247. http://search.proquest.com/docview/89694543?accountid=351.

2. Scarborough, Dorothy. On the Trail of Negro Folk-songs. Hatboro, Pa.: Folklore Associates, 1925. Pg. 7. Accessed on archive.org.