John Philip Sousa,1 commonly referred to as the “American March King” was a pivotal figure in not only conducting “American Music” starting from the end of the 19th century, but also spreading the term “American Music” outwards to countries outside of North America. Branching out the new style of music certainly gained popularity as other countries began to include styles such as ragtime, blues, and jazz into their musical framework. Little did these countries know that the composed and performed music of John Philip Sousa and the Sousa Band weren’t authentically composed from his ideas, but rather that of stereotypes and thievery of cultures appreciating this music long before “Americans.”

The stigma of whiteness in music is carried by the “broadly conceived European conceptualisation of music as a non-verbal symbolic system which becomes an object of verbal discourse, interpretations, and assessment in all human cultures. Talking about music allows people to organize sensed meanings, and further objectivise them,”2 says Professor of Musicology at University of Warsaw, Sławomira Żerańska-Kominek.

When new treatments of American Music were discovered during the late 1800s into the 1900s, white composers and musicians tried desperately to get their hands on it and make it their claim. JP Sousa was one of the many to do so, and was successful while doing it. Sure, many of his marches were authentically composed out of the musicality in his head, but many other compositions and performances were created out of stereotypes of traditions of non-white Americans.

First, take a listen to Sousa’s Band perform “Indian war dance,” written by Herman Bellstedt (1902)3. The 2:31 recording features an array of band members making sounds with their mouths, in an attempt to represent native indian songs. Not only are the sounds utterly racist to native indian songs, but the concept of the song itself proposes red flags to the “whiteness” of native indian music. Notating when band members should scream, while a band plays assorted notes based on traditions the Europeans passed down to American music theory creates an “us” vs. “them” feel. When diving into the composition itself, the song is all white interpretation based on non-lived experiences of the “others,” being native indians.

Another example of “whiteness” immersed into non-white originating music can be heard in Oscar Gardner’s “Chinese blues” (1915)4 performed by Sousa’s Band once again. The 3:55 song highlights a stereotypical idea that Chinese music is different because it is light and dainty. The entirety of the song features trills and bouncy melodies. News flash: not all Chinese music is light and dainty, but the misconception of white, American composers writing Chinese music completely misses this point. And to make matters even worse, the composer decides to throw on the term “blues” at the end of the song title. American writer Amiri Baraka describes The blues as being what was “conceived by freedmen and ex-slaves – if not as the result of a personal or intellectual experience, at least as an emotional confirmation of, and reaction to, the way in which most Negroes were still forced to exist in the United States.”5

What is the problem with the blues, in Chinese blues, you may ask? There is no element of blues in the song! Instead of implementing notes of dissonance to signify the pain and struggle the blues originally conveyed, the song sounds of joy, happiness, and music that would get crowds of people on their feet. Sounds a lot more like ragtime to me.

Although song titles are no longer extremely racist or stereotypical, this doesn’t take away from the past of American music, and how horrible acts could be seen as ways of entertainment to white populations. This is why it is important to reflect on our pasts. The past can never fully be forgotten, and Sousa’s take on “whiteness” in non-white originated music is one prime example of this statement.

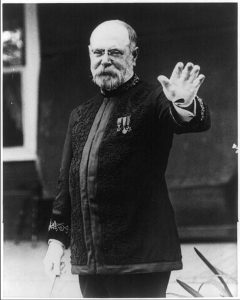

1“John Philip Sousa.” Library of Congress, January 1, 1970. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3b17070/.

2 Żerańska-Kominek, Sławomira. “‘The Whiteness’ of Music Analysis. A Gloss on Philip Ewell’s Lamentation over Schenker.” Musicology Today (Warsaw) 19, no. 1 (2022): 96–103. https://doi.org/10.2478/muso-2022-0007