While the Theater Owners’ Booking Association (or T.O.B.A.) had many high powered stars working on its circuit, Gertrude “Ma” Rainey is one of the players that continues to resonate with popular culture today. August Wilson’s mid-1980s play Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom and the 2020 movie adaptation of the same work are just a couple examples of Rainey’s massive influence in the current media whirlwind.

Yet, Ma Rainey’s influence was powerful even among her contemporaries on the T.O.B.A. circuit and her adoring audiences. Below are a couple of performance advertisements and reviews of Rainey’s work, which include nothing but glowing remarks regarding her artistry.

“Everybody is still talking about the glad rags that Ma Rainey displayed. She made about ump-teen changes and looked keener each time. Ma sang until she was out of breath, the audience called her back each time and she really did her stuff. She climaxed the deal by doing a ‘Paramount Black Bottom.’ This company is good enough far anybody’s house.”

“IN OLD KAYSEE.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jan 21, 1928.

“There are a number of performers singing the ‘blues,’ but when Ma Rainey sings them, nuff said. She has to take three or four bows every night.”

“Alexander Tolliver’s Big Show.” Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), January 29, 1916: 6. Readex: African American Newspapers.

Even a blurb from the Kansas Plaindealer speaks of her musical appeal transcending race:

“‘Ma’ Rainey is widely known to both white and colored lovers of crooney melodies. She was selected after careful canvas to make phonographic records and also to sing on the radio. Her tones are distinctive and have that peculiar resonance characteristic of color singers.”

“‘MA’ Rainey.” Plaindealer (Topeka, Kansas) THIRTY FIRST YEAR, no. THIRTY SIX, September 6, 1929: [THREE]. Readex: African American Newspapers.

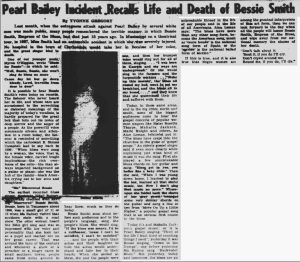

In an article published long after her death that details the horribly common instance of racism against African Americans across the United States, female journalist Yvonne Gregory writes about Ma Rainey’s extensive artistic reach on her musical contemporaries and her impact on blues music in general.

In her fairly short article, Gregory manages to create a chronology of notable blues artists, which just happen to be women. She describes how Ma Rainey discovered Bessie Smith when she “heard the little girl sing and was so impressed with her voice and personality that she took her as a pupil and started her on her great career.” Then, the author says that this influence and mentorship continues to occur among African American women — even if less direct than the Rainey and Smith story.

“Today it’s [] Mahalis Jackson’s gospel music; or it is Pearl Bailey singing ‘Tired of the life I lead, tired of counting things I need’; yesterday it was Bessie singing, ‘Down in the Dumps’; day before yesterday Ma Rainey sang ‘Backwater Blues.’ but yesterday, today, and tomorrow, the blues are an unbreakable thread in the life of our people and in the life of all Americans.”

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Side note: I could not find a recording of Ma Rainey singing “Backwater Blues.” I could only find recordings of Bessie Smith singing the tune, because she is the composer. So, I’m not sure if Gregory made a mistake in attributing this tune to Rainey, or if the origin story is different from the commonly accepted one.

-

-

-

-

-

At first, I thought the author’s mentioning of all women blues performers was accidental or merely common name associations. She connects performers that fall within this musical era through their similar sounds and stage personas, creating almost a mini-history of the genre. However, she takes her brief blues music history a step further with a claim that “Negro women are among the greatest interpreters of this art form.”

Simply, this tidbit is exciting for a couple of reasons. First, Gregory’s analysis of this phenomenon in the world of blues music fits almost perfectly with our current mapping project of the T.O.B.A. circuit and the routes of its many powerhouse women performers. Second, even back in the 1950s, women saw the effect of not only Ma Rainey, but also the collective of African American women who contributed in pioneering the popularity of the blues music we know (and even love) today. Here, we see a unique instance of African American women being lifted up, even though the world around them wants to tear them down. Therefore, like Yvonne Gregory, I “look forward to the day that all the people will honor [these African American women],” and I hope that our mapping project will shine a light on some of these powerhouses that many today might not even know.

![[African American man giving piano lesson to young African American woman]](http://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/pnp/ppmsca/08700/08779r.jpg)