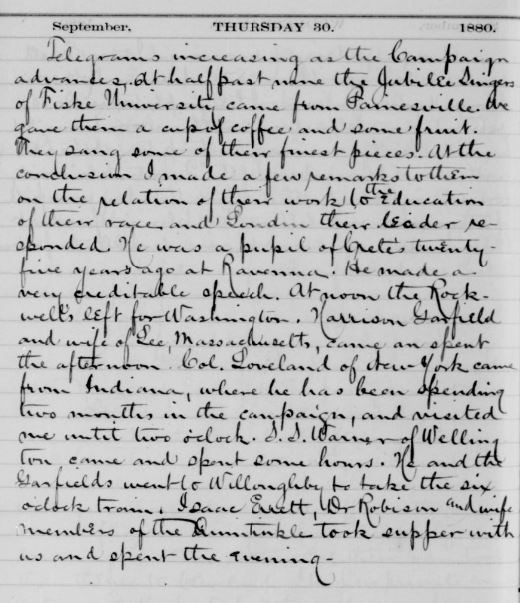

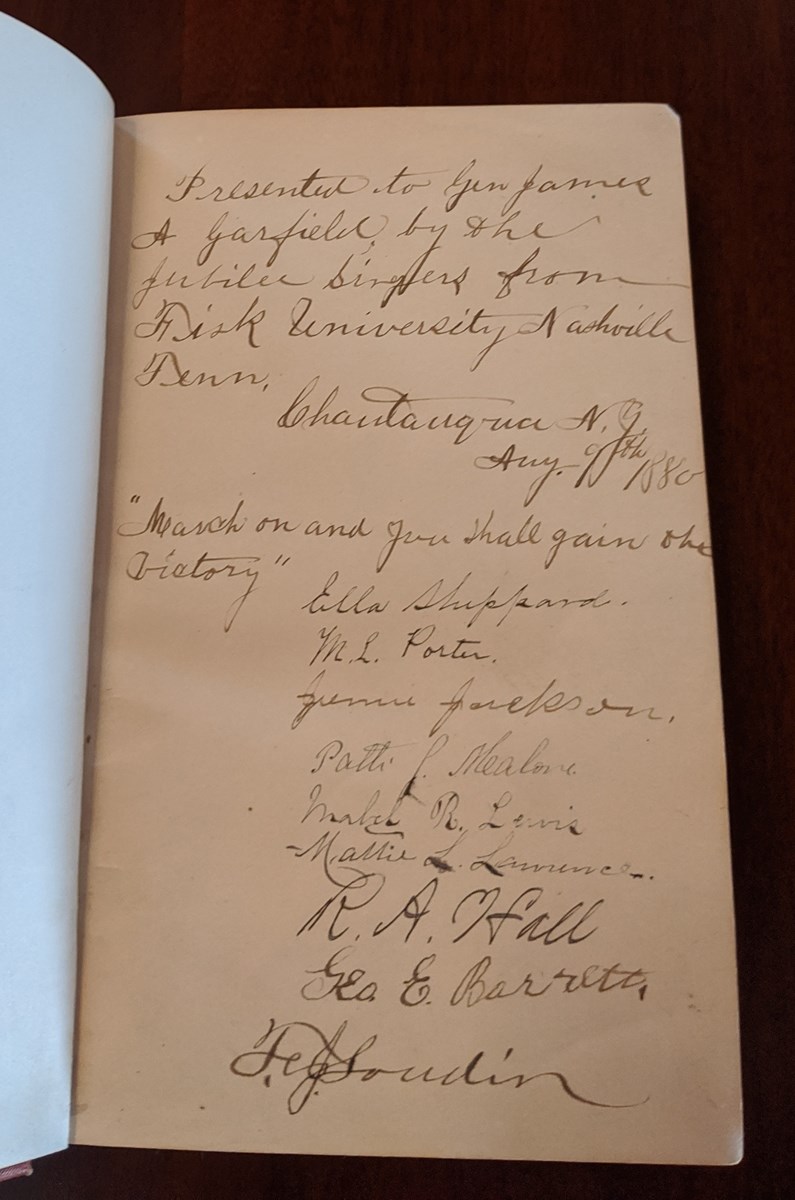

Blackface and minstrelsy feel as outdated as just about anything from the early 20th century but while the overwhelming idea of blackface is a strictly negative one, some black and brown artists are reclaiming the painting of their bodies for empowerment. Baseera Khan is a Muslim American contemporary visual artist working out of Brooklyn, NY who has been creating exhibits around the country for the last 8 years.

Baseera Khan’s Braidrage reclaims her identity in the representation and expression of her own physical body using oil, hair, architecture, and art. The dark paint on her body is especially important as a commentary on her race. Our conversation about minstrelsy in class assumes the negative use of black face paint related to minstrelsy, and we look at its use from a strictly historical viewpoint. However, the use of blackface has found a recent resurgence as a form on self-expression and power, taking back from racist traditions of the past and creating empowering and powerful artistic expression.

There is a long history of blackface in art leading up to exhibits like Khan’s, with varying degrees of controversy. While some of them turn a critical eye to the past, other artists misunderstand how their artwork can reinforce stereotypes and can further the disconnection between groups of people. Vanessa Beecroft is another artist who uses blackface in her artwork, who couples race with gender in her expressions.

[ iframe src=”https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/baseera_khan” width=”640″ height=”480″ ]

[ iframe src=”https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blackface_in_contemporary_art” width=”640″ height=”480″ ]