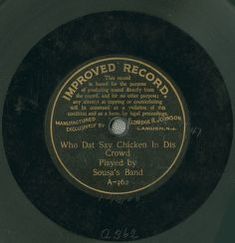

I know, I know, you’re disappointed this is not another installment of my world famous series Cohen Quest. Fear not, dear reader, for yet have an interesting history to uncover. After an obligatory “Cecil Cohen” and “Charles Cohen” search in the National Jukebox Collection, I found myself sorting the recordings by date; the first recording to pop up was that of a song called “Who dat say chicken in dis crowd?”, composed by a Mr. Will Marion Cook, and recorded by “Sousa’s Band”, conducted by Arthur Pryor.1

At first I was more than a little disturbed by the use of dialect and automatically assumed this was a blackface minstrel song and prepared myself for the worst as I looked up the contributors. Hoo boy was I wrong!

Will Marion Cook (1869-1944) was a prolific and accomplished composer and conductor; he studied at Oberlin College, the Berlin Hochschule für Musik, and under Antonin Dvořák at the National Conservatory for Music, and because racism prevented him from having a career in classical music he switched to composer popular music and was extraordinarily successful. His musicals Clorindy (1898) and In Dahomey (1903), composed for the comedy duo Bert Williams and George Walker, were the first all-black composed, produced, and performed musicals on Broadway.2

The text of Clorindy, where “Who dat say chicken in dis crowd?” comes from, was written by the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. The use of dialect, in this case, was not in mockery; at the time Clorindy was first performed, operetta and minstrelsy were all the rage. As it was one of the only ways black musicians could be successful, Cook and Dunbar wrote their musicals in the styles of minstrel shows to appeal to white audiences, and subsequently helped usher in a new era of musical theater.3 Listen to the tenor William Brown sing the original version of the song, and perhaps follow along with the lyrics:

There was once a great assemblage of the cullud population,

all the cullud swells was there,

They had got them-selves together to discuss the situation

and rumours in the air.

There were speakers there from Georgia and some from Tennessee,

who were making feather fly,

When a roostah in the bahn-ya’d flew up what folks could see,

Then those darkies all did cry.Who dat say chicken in dis crowd?

Speak de word agin’ and speak it loud–

Blame de lan’ let white folks rule it,

I’se a lookin fu a pullet,

Who dat say chicken is dis crowd.A famous culled preacher told his listnin’ congregation,

all about de way to ac’,

Ef dey want to be respected and become a mighty nation

to be hones’ Fu’ a fac’.

Dey mus nebber lie, no nebber, an’ mus’ not be caught a-stealin’

any pullets fun de lin’,

But an aged deacon got up an’ his voice it shook wif feelin’,

As dese words he said to him.Who dat say chicken in dis crowd?

Speak de word agin’ and speak it loud–

What’s de use of all dis talkin’,

Let me hyeah a hen a sqauwkin’

Who dat say chicken in dis crowd.4

There are a few things going on here: Cook and Dunbar were incredibly talented artists caught in a time in which, because of national trends and the distribution of money, they were forced to write in a style that was a bastardization and exploitation of their very recently enslaved ancestors. Perhaps this is one manifestation of DuBois’s “double-consciousness”: this second sight encourages black artists to incorporate the proclivities of white consumers to have a chance at success.5 We could easily track the long history of black artists capitulating to white sensitivities in order to survive, starting from enslaved instrumentalists performing at plantation balls as described by Eileen Southern. However, for the artists involved, this can also be a way to take back some power: their use of dialect and minstrelsy styles gave the production team a larger audience and greater notoriety in a time where all-black productions were rare.

1 Cook, Will Marion, Sousa’s Band, and Arthur Pryor. 1900. “Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd?”. Library of Congress National Jukebox. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-1762/.

2 Library of Congress. “Will Marion Cook (1869-1944)”, accessed Oct 4, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200038839/

3 Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. “minstrel show.” Encyclopedia Britannica, September 2, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/art/minstrel-show.

4 Cook, Will Marion, and Paul Laurence Dunbar. “Who Dat Say Chicken in Dis Crowd?”, Library of Congress Sheet Music. 1898. Notated Music. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016790971/.

5 Du Bois, W.E.B.. “Of Our Spiritual Strivings”. The Souls of Black Folk; Essays and Sketches. Oxford University Press, 2007, pg. 7-14. https://libcom.org/files/DuBois.pdf.