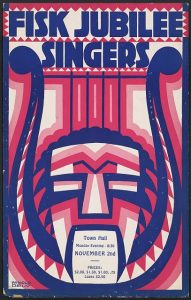

Musicians’ public reception begins before they play a single note. The advertisements for their performances preview who they are and what kind of music they make. I was captivated by a poster for a Fisk Jubilee Singers concert between 1910 and 1950, designed by Winold Reiss. The artwork offers insight into who they were performing for and what themes the performance might have had.

Winold Reiss, “[Graphic Design for Fisk Jubilee Singers.] [Concert Poster with Harp and Mask Motif],” still image, last modified 1910, accessed October 4, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/ resource/ppmsca.64409.

While the Library of Congress lists 1910 as the earliest potential date of publication, the fact that Reiss had not yet moved to America makes this improbable. Still, he was devoted to non-white subjects, known for his portraits of the Blackfoot and Blood Indians of Canada and the northwestern United States. The Reiss Partnership summarizes the perspective he brought to his art, stating that,

“His idealism challenges the notion that as Americans we are anything less than “us,” a totality that includes rather than excludes.”2

To be clear, Reiss should not be seen as a sort of white savior just for making art that centers Black and Indigenous folks. However, his idea of creating an inclusive American identity mirrors the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ history, and later, this poster.

The original Jubilee Singers’ rehearsal process matches the values with which Reiss made this flyer. Students in the ensemble taught the songs to each other, which their director then arranged.3 This collaborative process, much different from what I’m used to in choir, stems from the oral tradition of folk spirituals, which inspired the concert spirituals performed by the Jubilee Singers.

James Wallace Black, “Jubilee Singers, Fisk University, Nashville, Tenn.,” still image, last modified 1872, accessed October 4, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/ppmsca .39589.

As for the poster itself, bright colors and geometric borders surrounding the top letters caught my attention. An African mask within a harp is featured in the center of the advertisement. While the harp is known as a European instrument, there is no greater variety of harps than in Africa.4

Audiences, though, might have perceived the harp as a Renaissance instrument. Thus, it is notable that the African mask is within the harp: a prominent part, inseparable from the whole. The Jubilee Singers convey to potential audiences what musical identity they hold: a combination of African and European influences that form the American music they perform.

While I could not find information about the audience at this performance, one person who would have appreciated this poster is music critic Henry Krehbiel. While Krehbiel held undeniable racist beliefs, we also discussed in class that Krehbiel argued against the prevailing thought at the time that Black spirituals were not American folk music. Instead, Krehbiel noted that African idioms influenced these songs, but,

“They were created in America under American influences and by people who are Americans.”5

The Fisk Jubilee Singers’ poster tells us so much more than just performance locations and the cost of attendance. They make music from African American traditions which are inseparable from the whole of American music.

Footnotes

1 The Reiss Partnership, “Winold Reiss,” para. 3, accessed October 4, 2021, https://winoldreiss.org/life/index.htm.

2 The Reiss Partnership, “Winold Reiss,” para. 10, accessed October 4, 2021, https://winoldreiss.org/life/index.htm.

3 Sandra Jean Graham, “Jubilee Singers,” Grove Music Online, para. 3, accessed October 4, 2021, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002249936.

4 Sue Carole DeVale, “Harp,” Grove Music Online, sec. 3, accessed October 4, 2021, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000045738.

5 Henry Edward Krehbiel, Afro-American Folksongs: A Study in Racial and National Music, Republ., 4. print. (New York: Ungar, 1962), 26.

Bibliography