We haven’t talked about concert spirituals very much yet, but I think that they make a claim to authenticity that fits nicely into our discussions of geography and race. Similar to how the success of country music as a genre demanded ties to poor whiteness, concert spirituals maintained ties to high-society blackness. While looking through the Sheet Music Consortium, I came across 42 arrangements of the concert spiritual Deep River. The majority were credited to H.T. Burleigh who had an arrangement published during his time at G. Ricordi publishing house. The remaining versions, however, were by composers/arrangers of different races and nationalities.

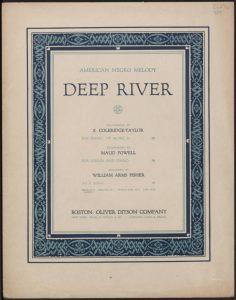

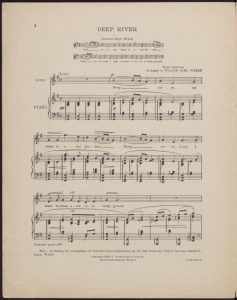

This 1916 arrangement by William Arms Fisher caught my eye. Like Burleigh, Fisher worked for a prominent publishing company, and spent most of his career as its vice-president.1 From my perspective, even though Fisher himself was white, this arrangement attaches itself to the tradition of Negro concert spirituals in two ways. First, is the inclusion of the original “American Negro melody” to which the musician(s) will refer to. Second, is the acknowledgement of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s contributions to the finished product. Not only is his name listed first on the cover (not common practice), but additionally Fisher writes on the bottom of the first page, “in making this arrangement the beautiful piano transcriptions by the late Coleridge-Taylor has been closely followed.” Would it need to be followed closely if it didn’t hold merit? I wouldn’t think so, which brings me to my next point. Coleridge-Taylor was a British composer who was inspired by the influence/culture of African-Americans like H. T. Burleigh, Booker T. Washington, and W. E. B. du Bois.2 The only authenticity he could claim, or that others could claim for him, was his blackness.3 And he did claim it to some degree — in 1904 he published Twenty-Four Negro Melodies for piano that are still played widely to this day. But did this understanding of concert spirituals — that a tie to blackness was necessary for sales — permeate white American households?

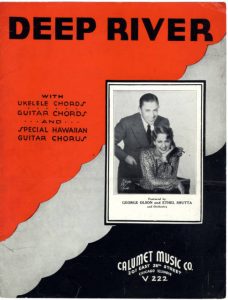

And another question. Was there a shift in necessity for claiming black authenticity? Based on the variety of sheet music, there was, and it happened around the 1930s when the sheet music for Deep River was marketed like a popular song.

This title page looks completely different than that of versions published during the 1910s-20s. For one, the performers in the portrait must have been mainstream enough for audiences to recognize them and want to buy the music. Second, the arrangement offers versions for ukelele and guitar. Just like our favorite High School Musical hits, this transcription gives audiences the chance to bring the musical fun home! From this example, and others like it, it seems like the racialization of Deep River was less important over time. Current discussions around “who gets to perform spirituals and why” suggest that concert spirituals have been re-racialized today, but when in history did this happen?

1 Karl Kroeger, “Fisher, William Arms,” Oxford Music Online, last modified January 20, 2001, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.09747.

2 Stephen Banfield, “Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel” Oxford Music Online, last modified November 26, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.A2248993.

3 This supports Amiri Baraka’s understanding of blackness as something that is essentialized, and naturally travels from black person to black person.