“Fiorello” was the 1959 Tony Award-winning hit that had made Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick a famous Broadway duo. Their next project: turning Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye Stories into a musical that “just happened to be Jewish.”1 Bock and Harnick had personally, for the most part, left Jewish religious observance and Yiddish behind. However, they still wanted to engage with Aleichem’s themes and historical implications with their next project.

2In 1964, Fiddler on the Roof made its Broadway debut at the Imperial Theater, encompassing perceptions before and after WWII of Jewish identity, as well as bringing “Jewishness” into popular American culture.

2In 1964, Fiddler on the Roof made its Broadway debut at the Imperial Theater, encompassing perceptions before and after WWII of Jewish identity, as well as bringing “Jewishness” into popular American culture.

Hal Prince, who was financially backing the show (and who also happened to be Jewish) made clear that he would only support the show if Jerome Robbins (who had just done West Side Story (1957)) directed. However, it was very unlikely that Robbins would want to work on the project, as he had made clear that he “didn’t want to be a Jew…he learned ballet to escape the wondrous and monstrous dance steps he feared he’d find by digging down to his Jew self.”3

However, in 1959, Robbins had taken a trip to Poland in search of the Jewish village Rozhanka, where his father was born and he had such fond childhood memories. However, the village had been destroyed in the war, which Solomon argues is what “primed Robbins to lavish such tenderness upon the fictional Anatevka” and he agreed to direct Fiddler.4

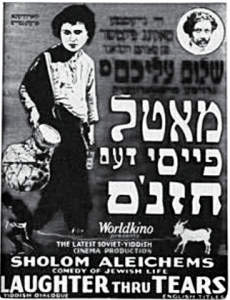

5Robbins drew from shtetl histories and hosted screenings of “Laughter through Tears,” a film that depicts Jewish life in pre-revolutionary Soviet Russia for the show’s costume and set designers in hopes that they would draw ideas for the show from it. Robbins also crashed Jewish weddings with cast members in hasidic dress in Brooklyn’s Borough Park to observe the “schnapps-fuelled dancing.” He even attempted to bring Othodox social customs to the rehearsal hall by enforcing gender segregation, but his attempt only lasted a few hours before the actors rebelled!

5Robbins drew from shtetl histories and hosted screenings of “Laughter through Tears,” a film that depicts Jewish life in pre-revolutionary Soviet Russia for the show’s costume and set designers in hopes that they would draw ideas for the show from it. Robbins also crashed Jewish weddings with cast members in hasidic dress in Brooklyn’s Borough Park to observe the “schnapps-fuelled dancing.” He even attempted to bring Othodox social customs to the rehearsal hall by enforcing gender segregation, but his attempt only lasted a few hours before the actors rebelled!

Robbins interviewed his father about his escape from Rozhanka and modeled Yente after his memories of his Yiddish-speaking maternal grandmother, whose “Jewish backward ways he’d previously despised.”6

7Zero Mostel, the original Tevye complimented Robbins with his superior knowledge of Yiddish literature and Jewish customs. It was Mostel who insisted that Tevye would never neglect to kiss the mezuza when passing through the doorway of his home, and Mostel who persuaded Harnick not to cut the verse in which Tevye dreams of a synagogue seat by the Eastern Wall from “If I Were a Rich Man.”

7Zero Mostel, the original Tevye complimented Robbins with his superior knowledge of Yiddish literature and Jewish customs. It was Mostel who insisted that Tevye would never neglect to kiss the mezuza when passing through the doorway of his home, and Mostel who persuaded Harnick not to cut the verse in which Tevye dreams of a synagogue seat by the Eastern Wall from “If I Were a Rich Man.”

The song was inspired by the 1902 monologue by Sholem Aleichem in Yiddish, Ven ikh bin a Rothschild (If I were a Rothschild), a reference to the wealth of the Rothschild family. The lyrics are based on passages of Aleichem’s “The Bubble Bursts,” one of his short stories.

In the first two verses, Tevye dreams of the material comfort wealth would bring to him. I see this as Tevye’s character being drawn to “mainstream American culture” that values consumerism and capitalism, especially in postwar society.

In the final verse, Tevye further considers his devotion to God, expressing his sorrow that his long working hours are preventing him from spending more time in the synagogue praying and studying the Torah. I see this as Tevye’s character further being drawn back by his Jewish roots and culture and away from the temptation of materialism.

Finally he ends by asking God if “it would spoil a vast eternal plan” if he were wealthy. I believe this is Tevye summarizing his internal identity conflict with asking God how he can balance mainstream culture with his strong faith.

1 Solomon, Alisa. Wonder of Wonders: A Cultural History of Fiddler on the Roof. New York: Picador, 2014.

2 http://www.wliw.org/21pressroom/j/the-jews-of-new-york/561/

3 Solomon, 2014.

4 Ibid.

5 http://s65.photobucket.com/user/rojaki/media/worldkino3_zpsdc698faa.png.html

6 Solomon, 2014.

7 Bock, Jerry & Harnick, Sheldon. “If I were a rich man.” Fiddler on the Roof. New York: Sunbeam Music Corp., 1964. http://mainemusicbox.library.umaine.edu/musicbox/pages/full_record.asp?id=VP_002550

Another great post, K. Something to think about as you work on your paper: Tevye’s desire for wealth certainly seems very American, but in Sholem Aleichem’s stories (which are a delight to read, if you haven’t already) wealth is also a ticket to full-time piety, which is a traditional value. In other words, poverty is ennobling but also makes it harder to worship as much as you’re supposed to, while wealth is corrupting but also an opportunity to get closer to G-d. Maybe some of the scholars you’ve read already deal with this seeming contradiction, or maybe you can find some literary scholars who write about Aleichem’s stories. Either way, consider dealing with this counterargument as you work to show Tevye as split between old/new identities.