Content Warning: Offensive language, racial slurs

There’s a common and very problematic sentiment in America that racism and racial oppression are things of the past, and this sentiment certainly applies to minstrelsy as well. While I like to think the majority of Americans would be able agree that minstrelsy was a deeply racist phenomena, a much smaller percentage has a grasp on just how influential it was and still in American popular culture. It’s easy to box it off, to say it was a bad episode of our history, to confine it to the past. But this is certainly not true. The research I did for this blog post made it abundantly clear just how recently minstrelsy was big, and just how absurd it is to claim it has no influence today.

The primary source I focused on was the sheet music for a minstrel song written in 1912, “At Uncle Tom’s Cabin Door”, music by Rubey Cowan and lyrics by Chas. Bayha. The lyrics of this song are extremely racist, romanticizing plantation life and claiming that enslaved people were happier before the Civil War. This recording is from 1913, and I’ve included the lyrics below. The picture shown in the video is the cover of the sheet music.

“In Eighteen Sixty, In Eighteen Sixty,

Those happy days before Emancipation,

‘way down in Dixie, ‘way down in Dixie,

merry darkies you would see.

They had their sorrows, that’s quite true,

But there were happy hours too,

Let’s go back once more,

Back before the war,

and we’ll see some jubilee.CHORUS.

See them dancing around,

Watch them prance on the ground,

Uncle Tom is gay, troubles fade away,

Hear them after each encore,

Roar for more,

Banjo’s strumming a tune,

Topsy’s acting like a loon,

There’s some celebration on the old plantation

At Uncle Tom’s Cabin door.Just hear them singing, Just hear them singing,

Those good ole darkey tunes they’re harmonizing,

Just see them swinging, just see them swinging

to the strains of “Old Black Joe.”

Here comes the Marsa from his ride,

There’s little Eva by his side,

Sime Legree’s away, bloodhounds are at play,

Those were happy, happy days.

Now, this overt racism is probably not at all surprising even if you know almost nothing about minstrelsy. But what caught my attention about this example is the composers, Cowan and Bayha. Neither of them are especially well known, but what they are known  for is not minstrelsy. It’s other forms of popular culture.

for is not minstrelsy. It’s other forms of popular culture.

We’ll start with Charles Bayha. He was a New Yorker best known for writing wartime songs during World War I, including I’d be proud to be the mother of a soldier. What little information I could find about him made no mention that he wrote minstrel songs, even though he evidently did. He died in 1957, as did Rubey Cowan, coincidentally. I bring this up because 1957 is still within living memory for some Americans.

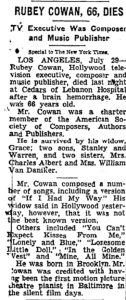

Rubey Cowan was possibly a bit more well known, given that he had an obituary written in the New York Times. Cowan is described as a TV executive, composer, and music publisher – he worked at Hollywood. I think what is the most striking to me about this is that Cowan – and many others who worked in entertainment – had careers that spanned the time from when minstrelsy was big to when TV was big. It simply was not that long ago that big executives at Hollywood had begun their careers in the minstrelsy industry. From this research it’s not hard to imagine the strong tie between minstrelsy and many other forms of American popular culture.

Bibliography

Bayha, Charles Anthony, William J Halley, and Rubey Cowan. At Uncle Tom’s cabin door. 1913. Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/jukebox-262541/.

Cowan, Rubey and Charles Bayha. At Uncle Tom’s Cabin Door. York Music Co., New York. 1912. Mississippi State University Libraries, Digital Collections. https://cdm16631.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/SheetMusic/id/24824

“Rubey Cowan, 66, Dies”. New York Times. July 30, 1957, 23. https://nyti.ms/3jxAWQt