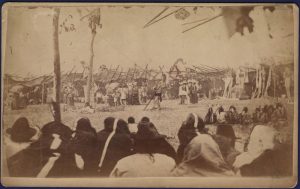

In August of 1970, an anonymous Sioux author wrote an article in the American Indian Leadership Council’s journal, The Indian, wondering about the claim that the modern Sioux have of over the Sun Dance.1 The ceremony, a celebration of the connection between the Sioux and the sun, was once an integral piece of Sioux culture. The eight-day event included ceremonies and dances that “reinforced ideals and customs of the Sioux society,” and a final day of physical pain as men danced while suspended from poles and looking directly into the sun. Although the Sun Dance was seen by the Sioux as the cornerstone of their culture and relationship with the sun, white Americans saw it as undesirable paganism. According to the author, once the Sun Dance was erased from Sioux culture, the other markers of Sioux life began to fade as well.

The Sioux Sun Dance has been reinterpreted by white American society in many ways, from a 1980 article in the Michigan Farmer that described the “curious custom” almost exclusively as a violent act,2 to an orchestral interpretation composed by Leo Friedman, recorded by the Edison Symphony Orchestra in 1903.3 Friedman, whose other compositions ranged from the well known “Let Me Call You Sweetheart,” to the lesser known “Coon Coon Coon,” used horns and jingling bells to play a simple melody, while a heavy percussion kept beat beneath. The end of the piece is marked by vocalizations clearly meant to be “war cries.” These musical choices exemplify the barbarism and other-worldliness with which Friedman wanted to represent the Sioux ceremony, and show no indication that it is about the religious significance of the sun. Friedman’s piece is instead an invention of Sioux music and culture.

If Friedman’s music was not a respectful interpretation of a Sioux Sun Dance, then it would be assumed that it would be up to the modern Sioux to revive or reinterpret the ceremony and its music. The author of the article in The Indian, however, wondered if the Sioux were still entitled to performing the Sun Dance ceremony. They asked “are we worthy to perform the Sun Dance– our forefathers failed to retain a religion they revered, and can we in all sincerity and honesty adopt the Sun Dance into our present society as a religion.” They worried about whether a reinterpretation of the Sun Dance by the Sioux would be “a religion or a tourist package.” The author’s feelings of a right of the Sun Dance are complicated in the context of the appropriation and misrepresent

ation of the Sioux ceremony by Friedman and others, and “the purge” of Native culture by white Americans, and a reinterpretation of the Sun Dance will have to take these new factors into account.

1“Sun Dance, Sacred?” The Indian (American Indian Leadership Council) 2, no. 3 (August 1970). Accessed 17 Feb. 2018. American Indian Histories and Cultures. http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Images/Ayer_The_Indian_1970_08Aug_06/0

1“The Sioux Sun Dance: One of the Most Curious Customs of a Warlike Indian Tribe.” The Michigan Farmer, April 5, 1890. Accessed 19 Feb. 2018. Proquest. https://search.proquest.com/docview/136546221?rfr_id=info%3Axri%2Fsid%3Aprimo