Porgy and Bess: Is It Worth It to Perform?

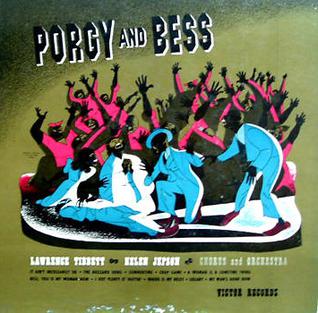

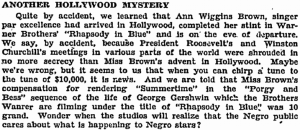

In 1925, an opera portraying love, tragedy, and conmen was published. Needless to say, it was a major success in opera performance as it has been celebrated as “one of the most celebrated American operas,” running for only 124 performances, it has made lasting impact on American music for it’s iconic music such as “Summertime”, and for it’s complex storyline. Although, the complex storyline based on a real man in the 1920s, Samuel Smalls, Can often be seen as a negative depiction of African-American culter and experiences. Although, black-owned newspapers and news outlets at the time raved heavily for the representation and storytelling depicted on the Broadway Stage.

In an analysis of “Porgy Bess” done by Lawrence Starr, Starr argues that “Porgy and Bess” it is difficult to say that the intention of creating the musical was supposed to be a means of mocking and critcizim of the African American community, rather a means of telling a story based off of the novel “Porgy” by DuBose Heyward. Starr states in his article that this is important considering that there were never any outward statements about the oper being solely about “the Black People” but more an opera of “Black People”. This argument was further emphasized through Starr’s study of Bizet’s “Carmen” in which Bizet had very opinionated views on the “gypsies” in the musical” (pg. 26) Nevertheless, it is unfortunate that one of the most infamous American Operas is about African American characters complicated love stories, gambling, cheating, killing, and disability. This can also become complicated considering that the story and the the opera were both written through the lens of a white man, which can, raise questions and flags of appropriation.

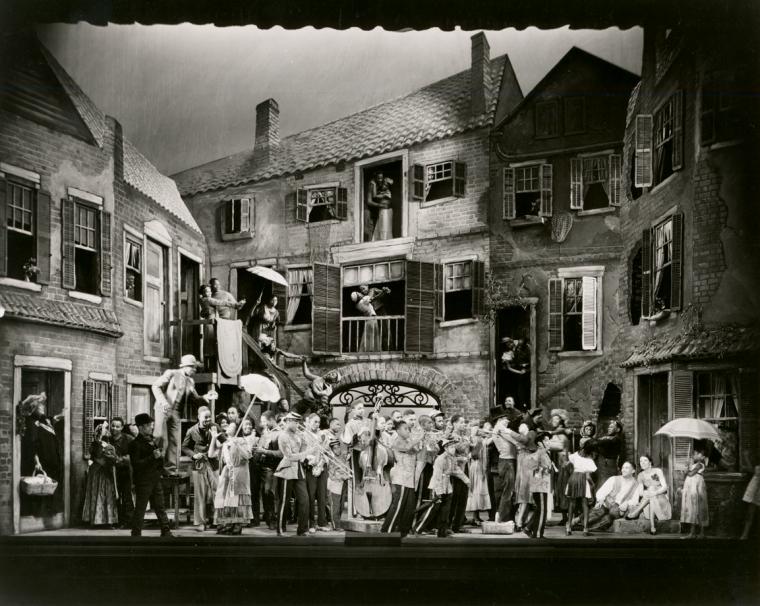

Although, at the time of it’s release and for some time after it’s debut on Broadway, Black owned press seemed to take a liking toward the opera and what it had done for black artists in the cast With the cast being an entirely black cast, this gave opportunities to black artists in which there would have not been an opportunity otherwise. In an article done by the Chicago Defender in 1942, Ethyl B. Wise focused on the children that were able to become involved within the musical as well as the amount of fun opportunities for the children within the musical. Wise states in the article, “Don’t you think it is grand that the actors including the children are all your people.” Although, this means we also need to take into consideration, (which Wise states in the article) that the children that are in the musical are also being exposed to a very mature storyline, which raised concerns while the parents were on the road with their children.

Although that the musical has been analyzed in both through negative connotations such as the the appropriation and black culture and the undermining nature of their life, the opera also offered plentiful opportunities for African-American performers in a time whic African-American performers were not seen in the limelight.

Work Cited

WISE, ETHYL B. “Let’s Go Backstage with Eight Little Stars in ‘Porgy and Bess’: BILLIKENS HOLD SPOTLIGHT IN ‘PORGY AND BESS’.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Dec 05, 1942. https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/lets-go-backstage-with-eight-little-stars-porgy/docview/492701821/se-2.

Noonan, Marie Ellen. 2002. ““Porgy and Bess” and the American Racial Imaginary, 1925–1985.” Order No. 3048850, New York University. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/porgy-bess-american-racial-imaginary-1925-1985/docview/305540446/se-2.

Starr, Lawrence. “Toward a Reevaluation of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess.” American Music 2, no. 2 (1984): 25–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/3051656.