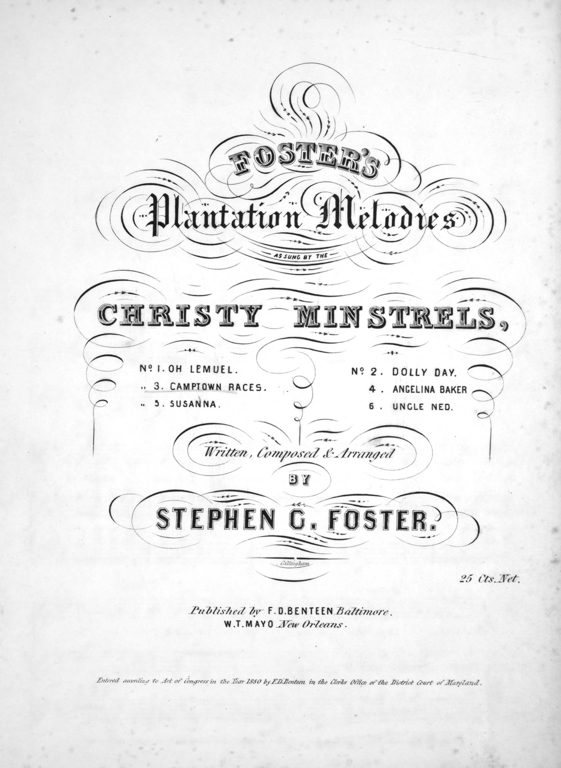

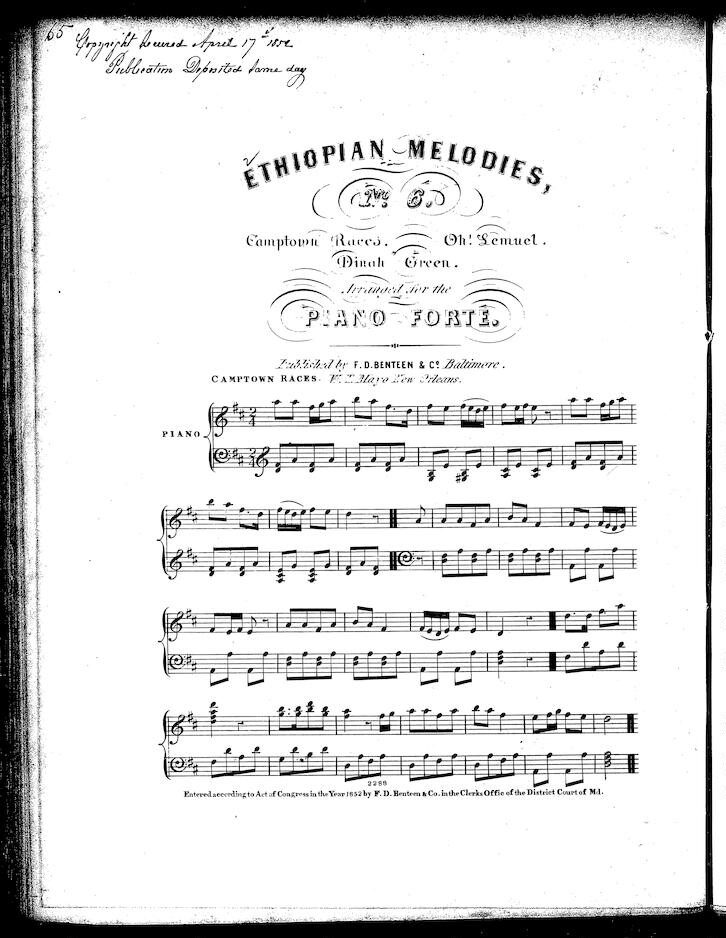

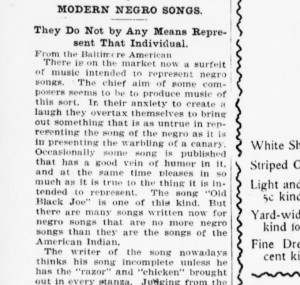

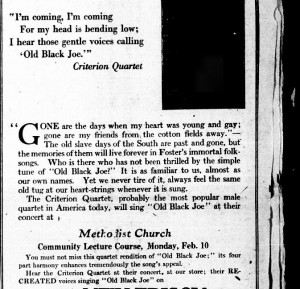

While many of these southern folk music pieces wrote by Stephen Forster presented sympathetic portrayals of African American characters, like the heartbreaking “Old Black Joe”(I mentioned in my first post), songs like “Camptown Races” and “Oh! Susanna” became linked with offensive stereotyped images of slaves, and was used in minstrel performance. Strangely, in the early and mid-twentieth century, in addition to using the songs to establish geography and time period, film scores and cartoons also began using Foster’s music as a way to negatively define a minority character’s station in life.

Although they by no means initiated the trend, film like Blazing Saddles used “Camptown Races” in a shorthand way of defining characters’ region (southern), race (african American), and personalities (hedonistic). The boss assumes his request was misunderstood. He wanted a “darky” song, like “Camptown Races.” In the film, when the boss starts to sing it, he wants to imitate a buffoon in minstrel performance with his untrained voice, awkward dance movements, and exaggerated “negro dialect”.

Cartoons like the Bugs Bunny shorts also used “Camptown Races” to strengthen the stereotype. The song was used to reinforce a drastic change in a character’s personality, or a costume change; this often happens when a character suddenly takes on blackface or even slave-like characteristics, as in Bugs Bunny’s transformation into a minstrel performer singing “Camptown Races” at the conclusion of Fresh Hare (1942). When we watch animated cartoons, how much does music shape our perception of the narrative? And why are Stephen Foster’s songs so prevalent in cartoon music in what has come to be known as animation’s golden age (1930s–1960s), especially in cartoons that depict African American slaves, blackface minstrelsy, and the South? Is it because Forster’s songs no longer deal with some exotic setting in another continent, but rather with real people in real places within the United States (Smolko, 348)?

As Daniel Goldmark says, “Minstrelsy never really died—it simply changed media.”

Work Cited:

Smolko, Joanna R. “Southern Fried Foster: Representing Race and Place through Music in Looney Tunes Cartoons.” American Music 30.3 (2012): 344-372.