It is difficult to determine exactly when influence from another culture turns into misrepresentation. Edward MacDowell, a white American composer wrote the piece Woodland Sketches, Op. 51: No. 5: From an Indian Lodge which was published in 1896. The piece begins with a fortissimo, perfect 5th interval, an interval which was often used to categorize “exotic” music. This is just one way in which MacDowell exhibits an inaccurate representation of Native American music. MacDowell’s composition undoubtedly brings up issues, both in his inaccurate, westernized representation of it, but also in his use of Native American culture without permission.

Chickasaw Composer, Jerod Tate

This conjures up the questions, is it always wrong to misrepresent a certain culture’s music by westernizing it? What if the composer is someone of that culture? Could that even be considered “misrepresentation”? Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate is a self identified citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and works to make Native American music relevant within the classical music world. One of his pieces, “Oshta”, written for the solo violin is loosely based upon Choctaw hymn 53.

Choctaw Hymn 53 came into existence as a consequence of Christian missionary work done in Native American land. Work to evangelize Native Americans was done essentially since the first Europeans came to the Americas. Religion was one way in which Europeans felt superiority, which often lead to a desire to teach Native Americans about Christianity in order to help them escape their “savagery”. Missionary work and evangelization is what lead to the creation of things such as the Choctaw Hymn Book, a bigger collection of hymns with Choctaw Hymn 53 comes from. Composed by Native American citizens, these hymns were considered a type of “hybrid music”; a combination between western hymns and a Native American style of music.

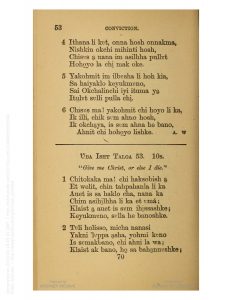

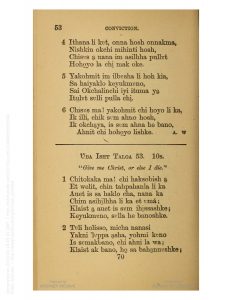

Choctaw Hymn #53 (2/2)

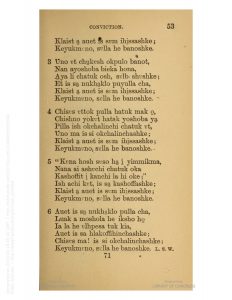

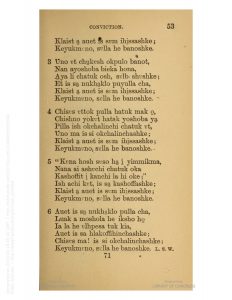

Choctaw Hymn #53 (1/2)

As seen in the images of Hymn #53, the words are all in Choctaw. Listening to this recording of the hymn, characteristics including the occasionally present dissonant harmonies distinguish it from traditional Christian hymnal music. The group singing is a characteristic which is also comparable to many other Native American music.

Listening to both Tate’s piece as well as the hymn it was inspired by, it is clear that they are vastly different, not only in their instrumentation, but in their melody and structure as well. Interestingly enough, Tate’s piece exhibits a perfect 5th double stop about 15 seconds in, making it possibly more similar to MacDowells’s intro than to the intro of the original hymn. Tate was clearly influenced by Native American music, much like MacDowell, but took it and made it his own.

To answer the questions I posed earlier, I would argue that no, a person like Jerod Tate cannot misrepresent his own culture, even if he is creating a sort of fusion between it and western culture. To argue with this, one might say that an implication of this fusion music is that it is a way of giving into assimilation by actively westernizing Native American culture. In reality, one cannot grow up in the United States without being exposed to western culture. I argue that even within one’s own identity, it is impossible to completely separate the western side from one’s ethnic and cultural heritage. Composers like Jerod Tate musically represent that dual identity within their work, thus making the Native American-Western fusion a presentation of pride of their culture and identity rather than a misrepresentation.

Sources:

- Choctaw Hymn 53: Chahta vba isht taloa holisso. Choctaw Hymn Book, Richmond, Presbyterian committee of publication, 1872.

- MacDowell, Edward. Woodland Sketches, Op. 51: No. 5: From an Indian Lodge. Barbagallo, James. Naxos 8.559010, 1994. CD.

- Mill, Rodney, Frank Oteri, and Susan Feder. “Orchestral music.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed February 18, 2018. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002224888?rskey=tPlwS5&result=2

- Stock, Harry. “A history of congregational missions among the North American Indians”. The Newberry Library, 1917. http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_MS_835

- Tate, Jerod. “About: Artist’s Biography.” Jerod Tate. Accessed February 18, 2018 http://jerodtate.com/about/

- Vba isht Taloa #53, Choctaw Hymn Book. Chahta Anumpa Aiikhvana: School of Choctaw Language.