We all know the feeling of standing out, and it’s no different in a group of singers: maybe you don’t quite know the words, sing a little off pitch, or a little too slow. Perhaps you’re afraid your singing might seem “unharmonius, complicated, strange” and perhaps, if you were a Methodist living in Cincinnati in 1837, you’d wake up one day to see those exact words printed in the newspaper under the ominous direction “Bad singing is forbidden.”

So then, where does this sentiment come from? And what exactly is “bad singing”?

Liturgical and congregational singing has a long history in Europe that was transported and developed in colonial churches. Psalm singing, or psalmody, was especially important to early worship functions — the practice of lining out, for example, was imported from England and involves a minister or leader singing or “lining out” each line before congregation sings it back (“Lining Out”). In the 1720s, a reform movement that promoted “correct” singing, singing schools, and instruments to help people stay on pitch began to gain traction, and slowly the traditional practices of congregational singing began to be replaced with new ones, called by the reformers “regular singing” (Southern).

Of course, not all churches agreed with the reformists. Methodists generally promoted and underscored the act of congregational singing as a devotion to God for all and frowned upon the performance of any difficult works by soloists or choirs, as these were seen as exclusive and inaccessible (Tucker). They were also vehemently opposed to the addition of instruments like the organ well into the 19th century (Temperley).

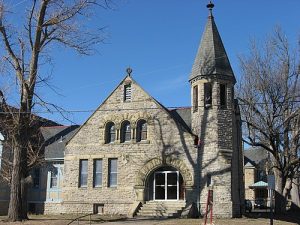

The Winston Place Methodist Episcopal Church, Cincinnati, constructed 1884

Many of these discourses about congregational singing were reflected in the Cincinnati newspaper article mentioned earlier, “Congregational Singing: Of the Spirit and Truth of Singing” published in the Western Christian Advocate in 1837. The article is very strongly worded, and very opposed to the introduction of “foreign elements” to congregational singing.

“Satan is ever watching to insinuate superstition and other foreign elements into the pure and simple worship of God.”

The “foreign elements”, later described as “rituals of heathenism”, are supposed to come from (and blamed on) several groups throughout the article — Jews, Pagans, Roman Catholics, some American Protestants, and British Methodists — and refer primarily to difficult, complicated, pieces sung by soloists and choirs or played by instrumentalists. To combat this, the article offers a list of rules and regulations for singing.

“These [regulations] are so Scriptural, so full of good taste, and so well calculated to do good, and to promote the very best congregational singing”

Included in these regulations is the requirement that singing must be done with understanding of what is sung, everyone must sing, and only the Methodist tune books should be used. Interestingly, it also instructs that singing must not be too slow, for this would be too formal. Slow singing is more characteristic of the old way of singing (Southern), which this author generally tends to support rather than the reformed way, so it’s an interesting contradiction to note that there is an instruction to avoid slow singing in this text. Perhaps this is an example of a musical concession that has already been made to the reformers at this point in the history of Methodism.

And to prevent any “heathen” elements being adopted, the article concludes with a list of “what here is forbidden”, a list which seems to precisely forbid anything related to the reform movement — singing schools, instruments, choirs, and complicated music are expressly singled out. And, just to drive the point home, it concludes:

“Bad singing is forbidden: it is bad when unharmonius, complicated, strange, or confined to a few”

And here we come full circle. And so, what is “bad singing”? In the case of this 1837 newspaper, it is not just a general complaint about the quality of singing, but rather a targeted critique of an important religious discourse of the time.

The author of this article would probably be pleased that everyone appears to be singing, but horrified that this modern day United Methodist Church hymn is complete with a church choir and organ.

Bibliography

“CONGREGATIONAL SINGING.: “OF THE SPIRIT AND TRUTH OF SINGING.” Western Christian Advocate (1834-1883), vol. 4, no. 33, Dec 08, 1837, pp. 130. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/magazines/congregational-singing/docview/126433359/se-2?accountid=351.

“Lining out.” Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Date of access 27 Sep. 2021,<https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000016709>

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. Third Edition. New York, NY. WW Norton Company, 1997.

Temperley, Nicholas. “Methodist church music.” Grove Music Online. . Oxford University Press. Date of access 27 Sep. 2021, <https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000047533>

Tucker, Karen B. Westerfield. “Methodism.” Grove Music Online. 16. Oxford University Press. Date of access 27 Sep. 2021, <https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002250214>