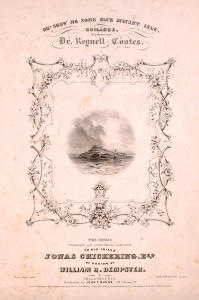

This cover of a piece of piano sheet music shows a dedication to Jonas Chickering. Jonas Chickering contributed greatly to the prominence of the piano in the 19th Century. Manufacturers like Chickering were reacting to a demand for the piano, but they also contributed and helped shape this demand. The piano was a sign of gentility and decorated the home. Within the 19th Century, the piano was an instrument for female amateurs. Women were expected to keep the domestic area refined, and since the piano was accepted as a sign of refinement, women seemed to like using it as a way to improve their home. This use of the piano as a source of refinement by women in the home is reflected in the many design changes that the instrument underwent. In the early 19th Century, manufacturers capitalized on this idea of women using the piano in the home, and they created a design that functioned as a piano, as well as a sewing table, which could be used for the sewing that specifically women would do.

This cover of a piece of piano sheet music shows a dedication to Jonas Chickering. Jonas Chickering contributed greatly to the prominence of the piano in the 19th Century. Manufacturers like Chickering were reacting to a demand for the piano, but they also contributed and helped shape this demand. The piano was a sign of gentility and decorated the home. Within the 19th Century, the piano was an instrument for female amateurs. Women were expected to keep the domestic area refined, and since the piano was accepted as a sign of refinement, women seemed to like using it as a way to improve their home. This use of the piano as a source of refinement by women in the home is reflected in the many design changes that the instrument underwent. In the early 19th Century, manufacturers capitalized on this idea of women using the piano in the home, and they created a design that functioned as a piano, as well as a sewing table, which could be used for the sewing that specifically women would do.

Women were also seen as having an emotional core to their being. Piano music published during and after the 1840s has an emotional character, and this demonstrates how the expectations for women, and beliefs about women also reflected the notion that the piano was a feminine instrument.

Women were also seen as having an emotional core to their being. Piano music published during and after the 1840s has an emotional character, and this demonstrates how the expectations for women, and beliefs about women also reflected the notion that the piano was a feminine instrument.

Manufacturers like those involved with Jonas Chickering perceived what people were looking for in a piano and in piano music. Their products came from preconceived notions about femininity and what people wanted and needed in music. It may seem like there is no way of telling whether or not manufacturers were reacting to the true demands of consumers, or creating a demand by perpetuating a perceived want, or need; yet, the manufacturers’ views and the composers’ views of women’s practical needs and musical tastes are evident.

Manufacturers like those involved with Jonas Chickering perceived what people were looking for in a piano and in piano music. Their products came from preconceived notions about femininity and what people wanted and needed in music. It may seem like there is no way of telling whether or not manufacturers were reacting to the true demands of consumers, or creating a demand by perpetuating a perceived want, or need; yet, the manufacturers’ views and the composers’ views of women’s practical needs and musical tastes are evident.

Sources

Crawford, Richard. America’s Musical Life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2001.

Dempster, William R. and Reynell Coates. “Oh Show Me Some Blue Distant Isle.” Philadelphia: John F. Nunns, 184 Chesnut St., 1841. Accessed October 23, 2017. http://levysheetmusic.mse.jhu.edu/collection/124/022.

Kornblith, Gary J. “The Craftsman as Industrialist: Jonas Chickering and the Transformation of American Piano Making.” The Business History Review 59, no. 3 (1985): 349-68.

Leppert, Richard. “Sexual Identity, Death, and the Family Piano.” 19th-Century Music 16, no. 2 (1992): 105-28.