While browsing the African American Newspapers database, I came across an article/add for Miller Lite entitled “Miller Lite supports Black History Month.” The article encourages readers to buy Miller Lite beer by telling them that during the month of February, a donation will be made to the Thurgood Marshall Black Education Fund for every case of beer sold. This offer is also advertised by a radio commercial featuring an upbeat version of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” featuring Deniece Williams, Al Green, Melba Moore, Roberta Flack, and Patti Austin. The Miller Brewing Company produced this recording in 1986, which the article states was the first recording of the song in 25 years.

We know this song today as the Black National Anthem. Personally, every time I sing or hear this song I am struck by the power of the lyrics, and the fact that the tune is so beautiful in its simplicity. Upon seeing this strange beer ad linked with “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” I became curious about the history of this song, and how it became Black National Anthem.

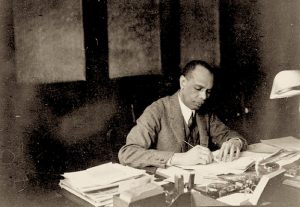

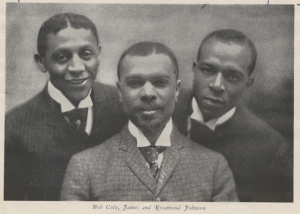

Contrary to common belief, this song was originally a poem, and was not intended to be an anthem by its composer. James Weldon Johnson wrote the lyrics to “Lift Every Voice and Sing” in 1900, and his brother, John Rosamond Johnson, set the poem to music. James Weldon Johnson was a lyricist, poet, international diplomat, civil rights activist, and an important voice in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. In February of 1900 he was asked to speak at President Lincoln’s birthday celebration, but instead wrote this song with his brother, which was performed at the celebration by 500 school children. While the Johnson brothers forgot about the song, the public did not. Children throughout the south continued to sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” and eventually it was sung all across the country. By the 1920s the song was so popular that the NAACP, with James Weldon Johnson as the chief executive officer, decided to make “Lift Every Voice and Sing” the official song. It is important to note that James Weldon Johnson called his song the “Negro National Hymn,” as he believed that a nation could have only one anthem, and didn’t want to further divide the country by separating the races.

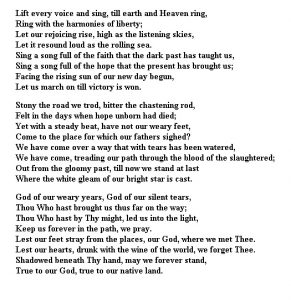

While the song has been performed in many different genres including classical, jazz, R&B, and rap, I was surprised to see it used for commercial purposes to ultimately sell beer. This juxtaposition of capitalism with a song that calls us to never stop fighting for justice in the face of America’s racist past and present is fascinating to me. I understand that the Miller Brewing Company probably had great intentions for this project, as they committed to donate some proceeds to the Thurgood Marshall Black Education fund, which “provided scholarship support to the nations 35 historically Black public colleges.” Despite this aim, it is troubling to me that Miller Lite chose a song whose anti-racist message is in direct opposition with capitalism, a system built on the backs of enslaved Africans – a system that profits by exploiting and oppressing African Americans. The disconnect here leaves a pit in my stomach.

Here is a link to a video of the 1984 recording session of “Light Every Voice and Sing” sponsored by the Miller Brewing Company: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwWhu8tw4nU

I would like to leave off with some additional recordings of this song. When I searched the Jazz Music Library for recordings of “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” all but one recording was instrumental, which invites us to make a comparison between renditions that include the lyrics and renditions that don’t. Here is a recording of Hank Crawford and Jimmy McGriff performing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” on saxophone and Hammond organ. To you, does the song still have the same effect without lyrics? Is it as moving or is there something lost? Personally, while the lyrics certainly indicate that the song is about an acknowledgement of the past and a confidence in the future, I am still moved by the instrumental versions. The tonal shift from major to minor is powerful in and of itself and somehow gives me a sense of determination without saying anything… is this simply because I already know the words? Here is a recording of the Manhattan Four singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing” for comparison.

I am including the lyrics to “Lift every voice and Sing” here, as I find it crucial to read and internalize the mobilizing message of the lyrics themselves, rather than learn about the history as a separate entity. These lyrics urge us to come together to strive for a better tomorrow, while always remembering the pain and struggle of the past. What would James Weldon Johnson say to us if he knew that the message of this song is still just as relevant and important 107 years later?

Sources

- Bond, Wilson, Bond, Julian, and Wilson, Sondra K. Lift Every Voice and Sing : A Celebration of the Negro National Anthem. 1st ed. New York: Random House, 2000.

- “Miller Lite supports Black History Month.” Chicago Metro News, February 25, 1989. Accessed October 6, 2017. http://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/HistArchive/?p_product=EANX&p_theme=ahnp&p_nbid=H56G59ROMTUwNzM0OTExNC4yMTA3OTk6MToxNDoxMzAuNzEuMjI4LjIyMQ&p_action=doc&s_lastnonissuequeryname=2&d_viewref=search&p_queryname=2&p_docnum=7&p_docref=v2:12912DF42BF1884F@EANX-12A25FAB38AEF4B0@2447583-12A25FABD35A4110@10-12A25FB12096C218@Miller%20Lite%20Supports%20Black%20History%20Month3

- “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” In National Public Radio. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1137484

- Edward A. Berlin. “Johnson, James Weldon.” Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed October 7, 2017, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/A2083946.

- The Best of Hank Crawford and Jimmy McGriff. Recorded January 1, 2001. Milestone, 2001, Streaming Audio. Accessed October 7, 2017. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C532408

- The Earliest Negro Vocal Groups Vol. 5 (1911-1926). Recorded January 1, 2000. Document Records, 2000, Streaming Audio. Accessed October 7, 2017. http://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Crecorded_cd%7C74556