Today, we understand that the media plays an important role in cultivating a culture. Blackface minstrels were one of the first forms of widespread or “mainstream” American Media entertainment. This means that it played an influential role in the mainstream media that exists today. Newspapers were another way of spreading information and culture to a large audience. The following primary sources are taken from a Newspaper publishing company called the “Now Orleans Daily Creole” in the year 1856.

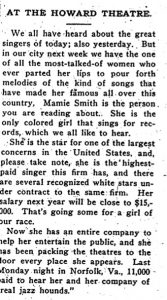

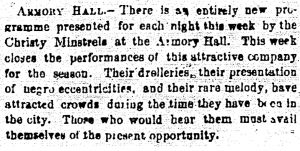

Advertisement in the October 20th, 1856 publication of the “New Orleans Daily Creole”. “Armory Hall.” New Orleans Daily Creole (New Orleans, Louisiana), October 20, 1856: 2. Readex: African American Newspapers.

The first excerpt regarding “Armory Hall” was published on October 20th.1 The referenced group called “The Christy Minstrels” was first formed by Edwin Pearce Christy, in 1842. The group consisted entirely of white performers in blackface. While this group was one of the first to travel as a unit and make a living off of it, by 1856(the year of the advertisements below) there was much more competition.

Earlier on in the group’s career one audience member reviewed their performance as being “more amused by their caricatures than charmed by the power or sweetness of their music”(Nathan, 158)2. This, in combination with the advertisement’s use of the word “eccentricities” proves that the audience understood and encouraged the lack of reality in Minstrel performances, practices, and caricatures. The music was not at the forefront of minstrelsy. It was there to mock one of the biggest aspects of a culture that was not their own.

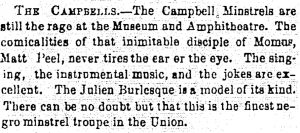

Advertisement in the November 24th, 1856 publication of the “New Orleans Daily Creole”. “The Campbells.” New Orleans Daily Creole (New Orleans, Louisiana), November 24, 1856: 2. Readex: African American Newspapers.

The second excerpt was published only about a month after the first, on November 24th.3 It gives a little more credit to the performance as a whole by referencing the vocal, instrumental, and comedic aspects of the show to draw the audience in. This second advertisement references another white minstrel group who performed in blackface called “The Campbell Minstrels”. The excerpt also takes note of their director so one can assume that this group had a following just like “Christy Minstrels”. The popularity of Minstrel shows in general began in the 1820’s and clearly continued into the 1850s. Throughout these thirty years we can see its development because this source references the style of “burlesque”. We also know that Edwin Christy is credited with creating the 3-act show4

. Knowing that these traditions or styles were new to the time period proves that Minstrels played a large role in the development of American theater and mainstream media.

It is also interesting to note that these performances were taking place in New Orleans. Many minstrels were popularized in the North, so to have these two traveling groups in the same southern location perform within a month of each other shows that minstrels were more common in the Southern United States than previously thought. While much of minstrel performance is lost on the modern audience or historian, the way they were advertised provides insight into perspectives of the average attendee.

1 “Armory Hall.” New Orleans Daily Creole (New Orleans, Louisiana), October 20, 1856: 2. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&sort=YMD_date%3AA&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=Minstrel&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A11B849020C1891B3%40EANAAA-11B95E171CE0DA50%402399243-11B86D14E5AC2270%401-11FAA70A71B3B3C2%40Armory%2BHall&firsthit=yes

2 Nathan, Hans. Dan Emmett and the Rise of Early Negro Minstrelsy. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity|bibliographic_details|500035.

3 “The Campbells.” New Orleans Daily Creole (New Orleans, Louisiana), November 24, 1856: 2. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&sort=YMD_date%3AA&page=1&fld-base-0=alltext&val-base-0=Minstrel&val-database-0=&fld-database-0=database&fld-nav-0=YMD_date&val-nav-0=&docref=image/v2%3A11B849020C1891B3%40EANAAA-11B95E58D0501DF0%402399278-11B86D154E124B80%401-1211B2645EE918AF%40The%2BCampbells&firsthit=yes

4 Lott, Eric. “Chapter 1.” Essay. In Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993.