There Is a Balm in Gilead is a well-known African-American spiritual with a rich history. Its origins cannot be pinpointed, a fact common to folk songs; however, musicologists have traced back to the first print publication as a way of identifying their mark of beginning. Most musicologists agree that the first publication of this particular spiritual is found in “Folk Songs of the American Negro” published in Nashville in 1907 and written by John Wesley Work, II who I will discuss later.1

The Original Jubilee Singers. John Wesley Work, Folk Song of the American Negro (New York: Negro University Press, 1915), 102.

The track here, recorded in December 1909 by The Fisk University Jubilee Quartet, was integral in the dissemination of this spiritual, especially to predominantly white audiences in the early 20th century. The Jubilee Quartet was a smaller product of the original Fisk Jubilee Singers which was a larger ensemble that toured on behalf of Fisk University, a university for African-Americans which opened after the end of the Civil War. The Fisk Jubilee Singers are best known for their performance tours which featured numerous spirituals and brought financial profits to support the university.2 Because of financial burdens, the ensemble was forced to cut down to a quartet in the early 1900s.3

“In the early days it was looked upon as a curiosity in the world of song, beautiful, entertaining but transient, for the world never considered it more than a commodity, through which one or two Negro schools maintained themselves.”4

This quote from John Wesley Work II, the conductor, arranger, and lead tenor for the Jubilee Quartet communicates some dissonance between the performance of spirituals in concerts so heavily influenced by financial motivations and the root of spirituals in the hardships of African-American slaves. Work was a leading force in collecting spirituals from oral tradition and transcribing them for publication and performing them on tours, yet acknowledged the history behind them in his book, attempting to go beyond the simple “commodity” that he felt audiences were attuned to.

“The reason why the Negro songs are so full of scripture, quoted and implied, is that for centuries the Bible was the only book he was allowed to “study,” and it consumed all his time and attention.”5

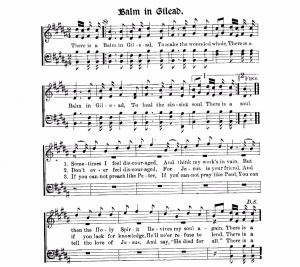

Balm in Gilead first published in John Wesley Work II’s book “Folk Song of the American Negro” (Page 43).

As we have brought up in class, spirituals often make reference to biblical passages. Balm in Gilead, in particular, centers around a text from Jeremiah 8:22 about hoping and longing for a better place.

The tension between origins and performance authenticity has been central to the discussions we have been having around black folk music in class. I continue to wrestle with whether it is appropriate to perform spirituals as a white person or to program them for concerts of predominantly white ensembles. Is there a way to respect and embody the grief that encompasses the ancestry of spirituals? Have we completely changed the intention or purpose of spirituals to suit our own needs, therefore exerting privilege, or is this just the nature of all folk music?

I welcome your thoughts toward these questions in respectful comments to this post.

1 Paul A. Richardson, “Hymnody,” Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press.