The opening imagery of Daniel Blim’s conference paper “MacDowell’s Vanishing Indians,” that vividly describes the setting of Chicago World’s Fair and Columbian Exhibition, stuck with me after class. What would it be like to walk down a corridor in the natural history museum to have real people and animals stare back at you? Historical newspapers and current scholars describe these events as half circus, half Night at the Museum.

Blim’s article introduced the idea of the “vanishing Indian,” a symbol of Native America(ns) that “could be reappropriated in the national imagination as a nostalgic figure rather than a living oppositional force.”1 We know that Native Americans were (literally) put on display at the 1893 World’s Fair, but in what other instances were Americans, and other nationalities in the case of the World’s Fair, witnessing and consuming Native American culture? Based on research via newspaper archives from the 19th-century, World’s Fairs, International Expos, and museums were the primary contexts in which non-Natives could interact with actual tribes.

To further investigate the “vanishing Indian” trope, I found an article originally printed in Scientific American in 1898. The article, titled “the Omaha Exposition and the Indian Congress,” described the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition of 1898. After quickly mentioning the technological advancements of fireworks, the author lays out the newest and most attractive addition to the Expo ⎯ the Indian Congress. The Indian Bureau of Washington, D.C. allocated $40,000 to find, deliver, and enclose 35 distinct Native American tribes. Nearly 500 members of these tribes were camped out over four acres of Expo premises. For three months, anthropologists, sociologists, and the general public could observe Native American musics, rituals, and all modes of living in between as if they were zoo animals.

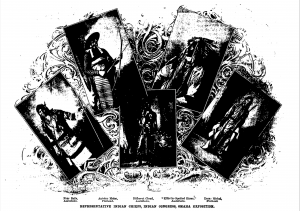

“Representative Indian Chiefs, Indian Congress, Omaha Exposition.” from left to right: Four Bulls, Assiniboin; Antoine Moise, Flathead; Different Cloud, Assiniboin; “Killed the Spotted Horse”, Assiniboin; Eneas Michel, Flathead

The article, read by thousands across the U.S. every year during this time, delivered the story triumphantly:

It is a curious and interesting fact that less than half a century ago the same docile Omaha Indians who peacefully doze by the camp fires within the Exposition gates were waging the war of the tomahawk and arrow on these very grounds, which is gratifying proof of the triumphal march of civilization.2

No wonder the “vanishing Indian” trope was recognized by music consumers and the general public ⎯ the only times Native Americans were presented as apart of American society were part of a curated experience:

The agents were instructed to send old men, and, as far as possible, “head men,” who would typically represent the old-time Indian, subdued, it is true, but otherwise uninfluenced by the government system of civilization… some [tribes] have become so civilized, like the Creeks, Choctaws, Cherokees, and Seminoles, that their presence would add little interest from an ethnological point of view; so the government did not assemble it most civilized proteges at Omaha, but the tribes it has conquered with the greatest bloodshed are the most important at the congress.3

Not only curated, but curated to show their defeat and vulnerability in the face of America’s power.