Blackface minstrelsy was the pinnacle of American entertainment for decades. In the early 19th century, white audiences and performers commodified and consumed Blackness by creating stereotypical characters. However, after the Civil War, minstrelsy evolved to remain relevant to the American public. I wrote in a previous blog post about how radio was minstrelsy’s medium in the 20th century. At the turn of the century, though, white troupe owners sought to keep minstrelsy relevant by a different medium: print.

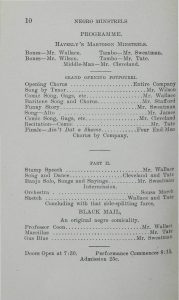

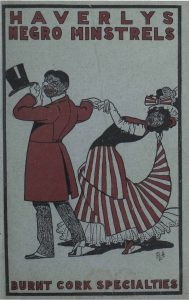

J.H. “Jack” Haverly, a white show manager, is remembered by historians as minstrelsy’s most successful promoter.1 In 1902, Haverly published a guide to minstrelsy for aspiring performers. He offers advice on organizing a troupe, many suggestions for jokes and songs, and of course, advertising strategies.

Guides like this were not unusual. I found two similar books published in 1880 and 1921 that contained similar material and advice in searching for this book. Despite the differences in time, the content had barely changed. Also constant was that Haverly and the other authors were writing to white amateurs. In his guide, he asserts that

“singing of comic songs and using good negro dialect are also essential.”2

This quotation implies that he is not writing for Black performers looking for any work they can get, but white aspiring performers.

In the late 19th century, Black minstrel troupes became more prominent as Black performers had fewer other job opportunities. White audiences began to see Black troupes as a more “authentic” portrayal than white troupes, threatening the white performers and managers who long ruled the industry.3

As this demographic shift of performers occurred, Haverly was growing his business. From 1873 he had managed Haverly’s Minstrels, a Black troupe. Over several decades, Haverly bought other troupes and theatres, consolidating his competition.4 He also started a shift in how minstrelsy was marketed, switching from a predominantly adult male audience to a family-friendly, even kid-centered audience.5 His economic fortune forced other troupes to keep up with his changes or fold.

With this context, it becomes clearer that Haverly’s guide to minstrelsy was part of his ongoing effort to keep minstrelsy relevant to the white American public. As Stephen Johnson wrote, minstrelsy was the center of the American entertainment industry. The only constant throughout its decades of prominence was that performers altered their bodies.6 The transition from white “professionals” to Black performers to white amateurs, accompanied by the switch to a family-friendly marketing scheme, is exemplified by Haverly’s guide.

Madeline Steiner best summarizes the evolution of minstrelsy that Haverly led. She posits that

“The popularity of the minstrel show was not a natural occurrence, but a condition carefully cultivated by profit-oriented capitalists such as Haverly.”7

While this is not a new revelation, Haverly’s guide is best understood as a capitalist tool to perpetuate the consumption of Blackness for the financial gain of white performers and show managers.

Footnotes

1 Robert B. Winans, “Haverly, J.H.,” Grove Music Online, para. 1, last modified September 22, 2015, accessed November 24, 2021, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002284597.

2 Jack Haverly, Negro Minstrels (Chicago, IL: Frederick J. Drake & Company, 1902), 5–6, accessed November 24, 2021, https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.stolaf.edu/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=Y5EE51UFMTYzNzcyNzE2OC40MDM5Mjk6MToxMzoxOTkuOTEuMTgzLjIx&p_action=doc&p_queryname=5&p_docref=v2:13D59FCC0F7F54B8@EAIX-147E02C4840557B8@4658-14A4E19D6DA4E020@3.

3 George K. Blake, “A Strictly American Institution: Neil O’Brien, Blackface Minstrelsy, and the Invention of White Catholic Identity,” Popular Music 38, no. 3 (2019): 383, accessed November 24, 2021, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2307346801?accountid=351&forcedol=true.

4 Robert B. Winans, “Haverly, J.H.,” Grove Music Online, para. 1, last modified September 22, 2015, accessed November 24, 2021, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-1002284597.

5 Madeline Steiner, “Winner of the William M. Jones Best Graduate Student Paper Award at the 2018 Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association Conference: The ‘Amusement Economist:’ J.H. Haverly and the Modernization of the American Minstrel Show,” The Journal of American Culture 41, no. 3 (September 2018): 305, accessed November 24, 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jacc.12937.

6 Stephen Burge Johnson, ed., Burnt Cork: Traditions and Legacies of Blackface Minstrelsy (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012), 2, 7.

7 Madeline Steiner, “Winner of the William M. Jones Best Graduate Student Paper Award at the 2018 Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association Conference: The ‘Amusement Economist:’ J.H. Haverly and the Modernization of the American Minstrel Show,” The Journal of American Culture 41, no. 3 (September 2018): 298, accessed November 24, 2021, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jacc.12937.

Bibliography