Mary Barnard Horne [1845-1931] was one of the first female authors of minstrelsy scripts. She wrote various musicals, school productions, adapted others’ performances for the stage and of course, minstrel shows. Interestingly, she dealt with the social and political status of women during this time in America where voting rights for black men and white women were similar. Here is one of her shows, entitled, “Jolly Joe’s Lady Minstrels.” The text is highly racist yet also is one of the first shows in which women were cast on stage. It contains a phrase in the introduction reading,

"Until recently the field of Amateur Minstrelsy has been open solely to the male sex. It was, however, only necessary for the weaker sex to turn its attention to burnt cork, to eccentric costumes, to negro songs, and to fun generally, to draw upon it the attention of the public and the verdict that, in this field as in many others, it could hold its own."1

Given that Horne’s plays were often performed for the white middle class, I was curious about the reception of a play which appeased one pillar of white male power but subverts the other. A quick search on newspapers.com reveals this 1913 review from a Brooklyn newspaper.

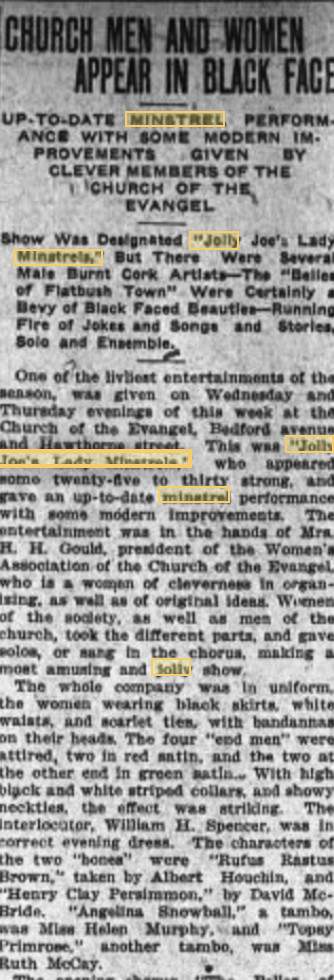

Clipping from The Chat, Brooklyn, New York. 22 November 1913.2

The subheading reads, “Up-to-date minstrel performance with some modern improvements given by clever members of the Church of the Evangel.” The performance was apparently put on by the leader of the women’s association at the named church. I find it fascinating that ‘modern improvements’ seem to refer to women’s rights but there is no consideration of the racism which the play contains. This is, as it turns out, quite a surface level observation of the fight for civil rights at the time. For context, Black men were granted the right to vote in 1870 whereas women were not granted the right to vote until 1920. During this time period, though, feminism took on many forms. Abolition-feminism equated the bondage of slavery to the bondage of women in order to fight for civil rights, yet the way this often played out privileged white women only. Clare Midgley writes, “In the United States, the fear of anti-slavery women was that their meetings would be disrupted by racist mobs.”3 Given this intersection, we can see how white women might take on the ‘modern’ cause for women’s rights without any concern for Black rights.

This little snippet from a seemingly niche subject, women in minstrelsy, is an example of a much broader trend in U.S. history, that is, white women weaponizing their status to further Black oppression. Zooming out now, we see the same trend continuing today, in the very same cities that minstrel shows were being performed. You may recall white woman Amy Cooper calling 911 on a Black man who asked her to leash her dog in Central Park, New York. In falsely accusing him of harassing her, she pandered to the cause of women while simultaneously posturing her white status. Can we blame her if she is just a product of our history? Yes, and we should look inward to change our own racist habits too.