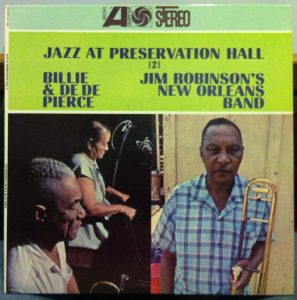

There is no question that jazz as a genre experienced much success throughout the 20th century. Around 1960, after it had begun to be replaced in popularity by rock n’ roll and bebop, its live performance was revived in part in New Orleans’ French Quarter.[1] Preservation Hall provided a space for aging jazz musicians to return to their art. “Almost all of the musicians have given up any work other than music, and have benefited from the new respect accorded to the New Orleans musician.”[2] Several jazz bands became affiliated with the space, among them the Wendell Brunious Band and Jim Robinson’s New Orleans Band. Manitou Messenger published an article in praise of the former,[3] and Halvorson Music Library has a record including recordings by the latter. But this success carried with it the baggage of preservation.

The back cover of the record suggests overtones unsettlingly similar to those of the “Vanishing Indian” phenomenon. The album–indeed, even the name of the hall which hosts the musicians performing on it–could be seen as portraying jazz as something which might fit well in a museum. If minstrelsy is understood to be an obsessive fascination with blackness, using primitiveness and exaggerated emotions as tropes to make something unsettling or intimidating approachable, seeing jazz as part of a bygone era that ought to be preserved meant society no longer feared blackness in music and could look to it for inspiration.

It should be noted that the founders of Preservation Hall, Allan and Sandra Jaffe, were white, and so could have had analogous attitudes toward jazz as MacDowell had toward Native music. That is, as a source of inspiration for new, less “other” art, even if the dominant race of performers at the Hall was still black.

But this is not the only presentation of these groups on the album. While it clarifies that performers at the Hall don’t typically take requests (suggesting a static, less improvisatory style), it says that they do play popular and folk music alongside the traditional pieces that are being preserved, with more “consistently better” performance than before. Many of the performers also personally played at the turn of the century, when jazz was first taking off. The Mess also calls out the mixing of disciplines to create Preservation Hall’s style, as well as the improvisation which does in fact take center stage.

St. Olaf’s interest, in a region of the country comprised mostly of white people, could be seen as merely scholarly, fascinated by something which was unique and “other,” or as genuine interest in a revived tradition with new ideas to offer. Regardless, interest in jazz from all demographics has grown; whether this is seen as a black art being taken by white artists after its “death” or new creative cooperation, the genre has carved itself a lasting place in the repertory.

[1] “History.” Preservation Hall. Accessed: http://preservationhall.com/hall/history/

[2] Pierce, De De, and Billie Pierce. 1963. Jazz at Preservation Hall, II. Atlantic.

[3] Hosch, Jennifer. 1992. “Artist Series introduces traditional style of New Orleans improvisational jazz.” Manitou Messenger. Accessed: https://stolaf.eastview.com/browse/doc/44949516