Henry (Harry) Thacker Burleigh is often credited as one of the leading Black Art Musicians of the 20th century, if not of all time. He is known to be the father of the concert spiritual (which could be debated, as the Fisk Jubilee Singers had been performing concert spirituals for some time by Burleigh’s birth). as well as a competent composer and performer of art music in the European style. Burleigh is also known for his connections to several figures of the Harlem Renaissance, namely WEB Du Bois and Booker T Washington.

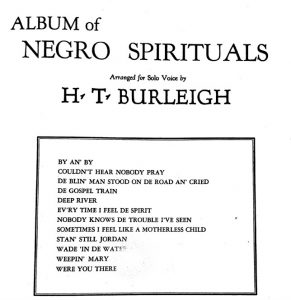

For this post, however, we’ll be looking at a specific part of Burleigh’s art, his “Album of Negro Spirituals.”

The collection I reference was published in 1969, 20 years after his death, however it contains Burleigh’s original markings, as well as footers with Burleigh’s own edits made during the composition and revision process. I’ll look at 3 of his most famous arrangements, looking at them through a theory lens to try and deduce influences Burleigh had.

This piece is the undisputed champion for “most famous spiritual.” If we look at Burleigh’s vocal line, it differs from most of the other songs in this collection, in that it does not use dialect. Burleigh is very specific about his use of dialect in singing, as we’ll see later on with “Wade in de Water.” While “Deep River” does not use the word “the” in it at all, which is an accomplishment in and of itself, and “the” is the most common dialectical word to change: we do still see “that” and “river,” both of which are commonly changed into “dat” and “ribber.” The accompaniment is sparse, with mainly rolled chords, however it does make use of some melodic material, reminiscent of some Schubert accompaniments. This can be seen most clearly in the last two measures of the first page.

This piece exhibits more of the stereotypical spiritual traits, with a fast, agitated, syncopated piano accompaniment. This style is often likened to drums or more rhythmic performances, which is commonly associated with spirituals here. The text is also in dialect, with words like “de,” “a-goin’,” and “dat.” Furthermore, we see a common them of spirituals, which is a reference to Moses and the Israelites. This make sense for a source material for spirituals, as Moses famously led the Israelites out of slavery, a plight the African slaves in the United States were all too familiar with.

Sometimes I Feel Like A Motherless Child

For our final piece, we have a bit of a hybrid in styles. This seems most in line with what we’ve talked about for Burleigh’s views on Black music as art music. It takes source material and performance stylings (dialect), and combines it with a European sense of harmony and texture. The piano texture would not feel out of place in a Brahms or Wagner lied, while the melody has a certain ebb and flow more reminiscent of a work song. The constant forward and back drives that home, while the crossing countermelodies in the piano, seen best during the refrains of “a long way from home.”

As we can see from these three examples, Burleigh wrote in a predominantly European style, using spiritual melodies as inspiration, but not attempting to stick to a folk tradition of performance. There are times when he leans into the folk origins a little more, particularly on Wade in de Water, but this makes sense thematically. Wade in de Water is neither hopeful nor sorrowful, but provides specific instructions for escaped slaves on making it to freedom (wading in rivers helped to mask their scent from tracking dogs). Nevertheless, the piece is included alongside works closer in style to Burleigh’s secular art music, showing its pedigree as art music.