While the spiritual tradition has a long history in the United States, dating back undoubtedly to the first slaves taken from Africa and brought to the colonies, it can be difficult to trace a lineage of sorts. This can be due to a number of factors, but the most prevailing is the fact that slaves were not seen as people, and thus could not have a culture worth documenting. Thus it fell on free African-Americans to document this culture, a task that was blocked at every turn by the segregation and racism present through the 20th century. Then take into account how many freed slaves had enough musical training to create a published representation of their music, training that was denied to them by conservatories on the basis of their race, and you can start to see the problem.

While the first published book of spirituals was “Slave Songs of the United States,” it was written by three white authors who sought to collect the music of slaves shortly after the dismantling of the institution of slavery.

This collection was published in 1867, and while interesting and insightful, is still a representation of Black music, specifically slave music, by white authors. This brings to mind a common saying in modern choirs, especially those that are predominantly white, “we can’t sing this spiritual because we don’t know what it was like to be a slave.” A common counterargument is that nobody knows what it was like to be a slave, since it has been so long since the institution of slavery was abolished. With this book, however, the compilers didn’t know what it was like to be a slave, while the people they collected from TOTALLY DID. Like they were actual slaves, who had just been set free 2 years earlier. Does this mean that the white authors misrepresented the sentiments of their queries? Probably if we’re being honest, but we’d have to look to the former slaves for that insight, and many of them were illiterate (both musically and linguistically) due to those same racist institutions.

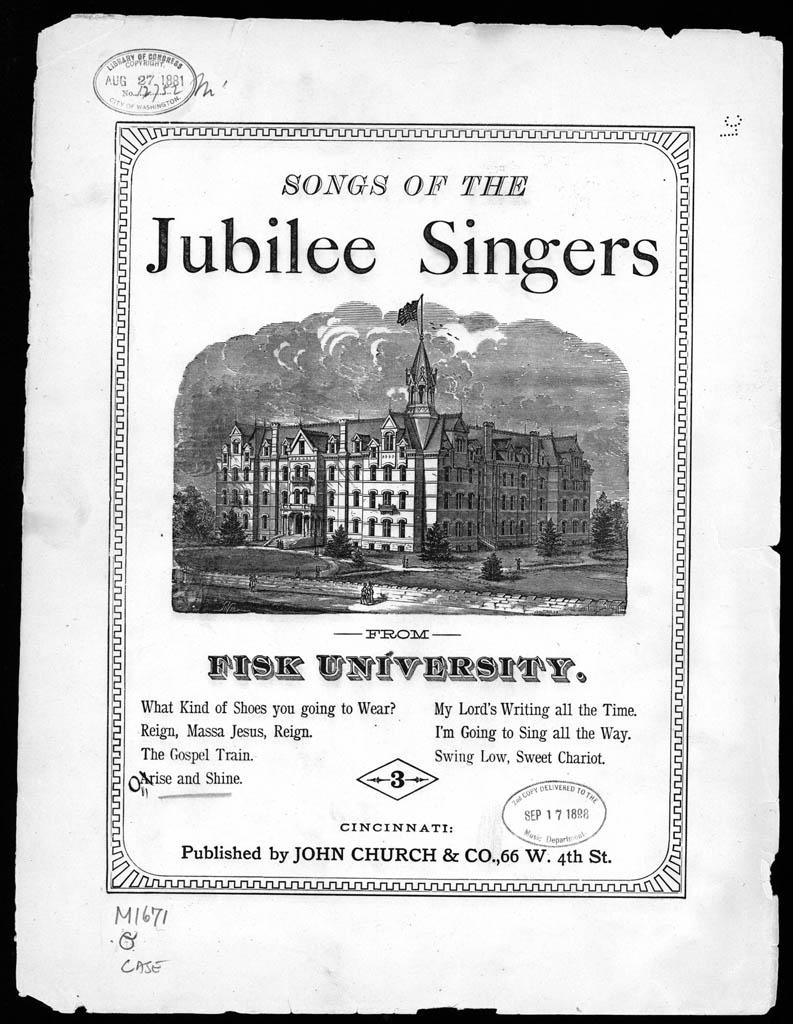

Enter Fisk University, one of the first educational institutions founded by and for formerly enslaved persons. This university was founded in 1866, shortly after emancipation, with the goal of providing the education so long denied to African Americans. You can probably see where I’m going with this, being a musician who just brought up Fisk University, but it’s Fisk Jubilee Singers time. The Jubilee Singers introduced the Spiritual to the world in 1871, and published this folio of sheet music in 1881 (that’s when the stamp of copyright for the library of congress is dated).

This folio contains seven works arranged by the Jubilee Singers, all but two of whom were former slaves. These publications, made famous by the tours of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, are directly responsible for the popularity of the concert spiritual. The Fisk Jubilee Singers proved that their folk tradition made for just as high quality art music as any other, and brought the idea of Black excellence to the stage as early as 1871. We’ve talked in class about recognizing what is representative of a style and what is an appropriation or perversion. This publication by the Fisk Jubilee Singers is perhaps the most definitive way to see how former slaves viewed their music, and the continued performances of the group give us that direct lineage to the source that we so long for.