What makes music black? Is it the performer? The composer? The performance style? While not many newspaper blurbs or display ads explicitly grapple with these questions, even seemingly innocuous clippings contribute to the conversation.

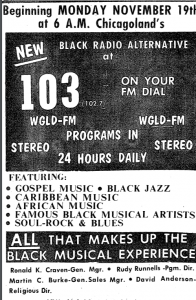

Sonderling Broadcasting Corporation, “New Black Radio Alternative,” Chicago Defender, November 17, 1973, Proquest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender.

A display advertisement from a 1973 issue of the Chicago Defender proclaims a “New Black Radio Alternative,” boasting that the station includes “All That Makes Up the Black Musical Experience.”1 This type of bold statement doesn’t tell us what makes music black, but it does validate our curiosity. The ad implies that there is such a thing as a universal “black musical experience” that can be neatly boxed and encapsulated. This very assumption is what prompts us to try to define black music. Many of the scholars we have read in class touch on this idea; for example, both Amiri Baraka and Samuel Floyd might agree that some black essence underlies black music, whatever it may be.2,3

Another short newspaper article in the Chicago Defender from just a few months prior to the radio advertisement espouses a similar belief in the existence of a quintessential “black experience.” In his short article, Earl Calloway discusses the fact that Columbia Records has just begun to record not only jazz, blues, and folk music, but also classical music by black composers. Calloway lauds these composers as having “dipped their pens into the core of the black experience and brought to surface ingenious creative music unlike any that exists today.” 4

Earl Calloway, “Columbia to issue classic black music,” Chicago Defender, July 23, 1973, Proquest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender.

There’s a lot to unpack here. At the base level, Calloway reinforces the existence of a universal black experience that is somehow part of what defines “black music.” But he also complicates his portrayal of black music by creating a hierarchy. He implies that classical music by black composers is better than other music, especially the standard “black popular music” that has already been recorded for sixty years. Earlier in the article, he asserts that “many composers have taken ethnic ingredients and transformed their earthy rhythms and simple melodies into the more complex sonata form.”5

This almost implies that classical music by black composers transcends ordinary black music, which Calloway seems to dismiss as “simple” and “earthy.” It is unclear if Calloway would even directly consider music by Joplin, Coleridge-Taylor, or Price to be “black music,” or if he would think of it as white music composed by black artists. Such complications always lead us back to the question: What makes a music black?

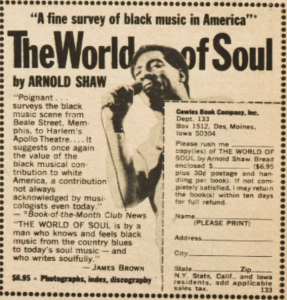

Cowles Book Company, “The World of Soul,” Village Voice, June 25, 1970, Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950-1975.

We come full circle with another advertisement in a 1970 issue of Village Voice at Bowling Green State University. The ad is for a talk described as “A fine survey of black music in America,” given by Arnold Shaw, the author of a book called The World of Soul.6 This again hearkens back to Samuel Floyd’s argument that black music has some cultural memory, or soulfulness, at its heart.7 So is it this characteristic that defines black music? I don’t think this question, or any other concerned with defining black music, is one that can or should be answered definitively; however, it is certainly fascinating to see that even the most commonplace advertisements and articles contribute to both the asking and answering of these questions.

2 Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Perennial, 2002.

3 Samuel Floyd, The Power of Black Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

4 Earl Calloway, “Columbia to issue classic black music,” Chicago Defender, July 23, 1973, page 10.

7 Samuel Floyd, The Power of Black Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995, page 10.

Works Cited

Amiri Baraka, Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: Perennial, 2002.

Cowles Book Company, “The World of Soul,” Village Voice, June 25, 1970, Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950-1975, http://www.rockandroll.amdigital.co.uk/Contents/ImageViewer.aspx?imageid=876210&searchmode=true&hit=first&searchrequest=doc&pi=1&vpath=searchresults&prevPos=586523 (accessed October 10, 2019).

Earl Calloway, “Columbia to issue classic black music,” Chicago Defender, July 23, 1973, Proquest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender, https://search.proquest.com/hnpchicagodefender/docview/494005840/C6B6337678684743PQ/4?accountid=351 (accessed October 10, 2019).

Samuel Floyd, The Power of Black Music. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Sonderling Broadcasting Corporation, “New Black Radio Alternative,” Chicago Defender, November 17, 1973, Proquest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender, https://search.proquest.com/hnpchicagodefender/docview/493926205/pageviewPDF/87620304615C470CPQ/1?accountid=351 (accessed October 10, 2019).