“Beyond the obvious fact that you are black, is your music black music?”

“No.”

“Why?”

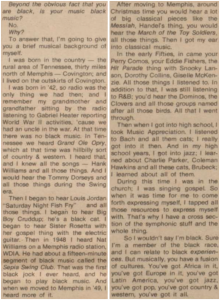

“To answer that, I’m going to give you a brief musical background of myself.”1

Excerpt of Isaac Hayes’ interview in The Los Angeles Free Press1

So begins an excerpt from an interview of the “black superstar” Isaac Hayes from a 1972 issue of the Los Angeles Free Press, in which Hayes discusses the blackness of not only his music, but himself. He recounts hearing a “hillbilly sort of country & western” music in his early childhood before hearing any swing or other black music. In addition to this, he went through many other phases, including multiple classical music phases, and only after that started learning jazz, while also singing gospel in church. He concludes:

“So I wouldn’t say I’m black. Sure I’m a member of the black race, and I can relate to black experiences. But musically, you have a fusion of cultures. You’ve got Africa in it, you’ve got Europe in it, you’ve got Latin America, you’ve got jazz, you’ve got pop, you’ve got country & western, you’ve got it all.” 1

This could be seen as a quite liberating view of a black musician’s music—almost transcending race, identifying aspects of his music that are grounded in many traditions. However, Hayes also takes the interesting step of applying this back to his race: “I wouldn’t say I’m black.” Being racially black and having black experiences isn’t enough to be black in the larger sense, which in Hayes’ view seems to include something more. When asked what he would “classify as pure black music,” he points to “songs expressing the black experience in the ghetto . . . that’s black music.”1 So if he made that kind of music, would he be more black? This, to me, is a surprisingly narrow view of what it means to be black.

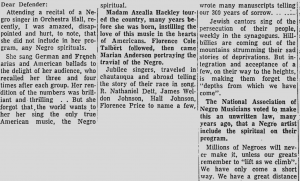

Beginning of letter in The Chicago Defender2

A letter in a 1965 issue of the Chicago Defender reflects a related view: “Attending a recital of a Negro singer in Orchestra Hall, recently, I was amazed, disappointed and hurt, to note, that she did not include in her program, any Negro spirituals.” The letter then gives examples of musicians who “wrote many manuscripts telling of our 300 years of sorrow,” but argues that now “integration and acceptance of a few, on their way to the heights, is making them forget the ‘depths from which we have come.’”2

This is not arguing that one must perform a certain music to be fully black, but rather that being black necessitates the performance of a certain music. It makes a compelling argument for black musicians to remember their history, but how much must the music one performs be rooted in their history? If black people must absolutely perform “black” music, this forges a link between the musician and their music that leads back in the direction of Hayes’ idea of black music and its connection to black identity. There can be clear benefits to connecting identity with music, but to connect them in such a way that one cannot exist without the other risks whittling them both down to an essence that fails to adequately represent either.

1 Van Ness, Chris. “Isaac Hayes: Superstar behind the soundtrack for Shaft.” The Los Angeles Free Press, Jan 14, 1972. http://www.rockandroll.amdigital.co.uk/Contents/ImageViewer.aspx?imageid=1101225.

2 Ruth, Smith McGowan. “Reader Disappointed when Singer Omits Negro Spirituals.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Feb 06, 1965. https://search.proquest.com/docview/493112600?accountid=351.

“Isaac Hayes – Theme From Shaft (1971).” YouTube video, 4:39, posted by Alamo YTC Germany, Oct 7, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q429AOpL_ds.