In the following video from the Popular Culture in Britain and America database, several different scenes are depicted from the protests surrounding the Democratic Party Convention of 1968, when Hubert Humphrey beat out anti-war candidate Eugene McCarthy for the presidential nomination (1). The protests and Convention took place in Chicago, and the protests were led almost exclusively by students. It’s kind of remarkable that, much like the history of minstrelsy, many of the events of these protests have vanished from the country’s collective memory. There were extreme shows of police brutality and repression of the free press, and yet like so much history that is distasteful, it is rarely taught or discussed.

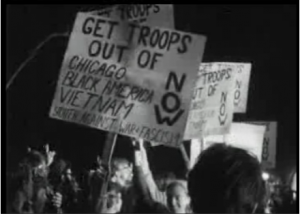

Depicted left: a protester’s sign, which says,

“Get troops out of Chicago, Black America, Vietnam NOW! Stoners Against War and Fascism” (2)

While this video has very poor sound quality and jumps around a great deal, one of the things that I noticed was that it featured very little of the Black America mentioned in the sign, with the exception of the brief shot beginning at time 8:54 and ending at about 9:23. In this clip, although the audio does not line up with the video, you can hear someone drumming and leading a call and response and a group of “African American people dancing to music and chanting,” as the database description says. This is our only taste of one of the major features of the anti-war and countercultural movement of the 60s and 70s – protest music.

Watch the video here: http://http://www.rockandroll.amdigital.co.uk/video/videodetails.aspx?documentId=889264

Black musicians and their music featured prominently in the anti-war movement – especially folk musicians, although there were many rock and roll musicians as well. Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, and the all-white folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary are just a few of the most famous musicians who wrote protest music during this time (3).

This struggle against widespread violence is just a continuation of the history we have been learning about in class. Like with every other genre or group of people we have discussed, music has an important role to play in both representing a movement or group to the rest of the world and in moving events forward in its own way. In protest music, this is by being a platform for viewpoints to be shared and by being a unifying force for those who hold the same (or similar) views. Protest music pushes on people’s conception of right or wrong, and thereby identity within those norms, in their society by working through stigmatized forms and symbols – in the Vietnam protests, these included connections to the Civil Rights movement and use of rock and roll and drugs (see Stoners Against War and Fascism, pictured above).

Works Cited:

- Editors of History.com. “Protests at Democratic National Convention in Chicago.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 21 July 2010, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/protests-at-democratic-national-convention-in-chicago.

- Huntley Film Archives. “Anti-Vietnam War Protests in Chicago during the Democrat Party Convention, August 1968.” Popular Culture in Britain and America, 1950-1975, Adam Matthew, 2011, www.rockandroll.amdigital.co.uk/video/videodetails.aspx?documentId=889264.

- Lindsay, James M. “The Twenty Best Vietnam Protest Songs.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 5 Mar. 2015, www.cfr.org/blog/twenty-best-vietnam-protest-songs.