During the Civil Rights Movement, hymns were used by protestors, white and black alike, as a unifying, peaceful statement. Time and time again, protestors chose to arm themselves with hymns, which is evident in write-ups like the ones below from the Chicago Defender.

These peaceful protests appear to have been so prevalent in the mid-1960’s that they were given their own nickname— “hymn-singing meetings.” I found myself asking the question, “Why hymns?” How did a whole genre of music rise to unify the movement? Why not African American spirituals, or another genre?

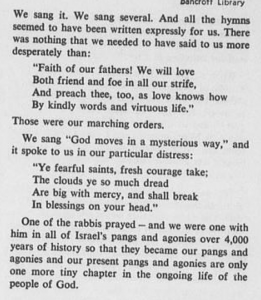

An argument could be made that the protestors chose to sing hymns because of their religious significance. The Civil Rights movement, was, after all, based upon largely Biblical ideas (such as loving your neighbor as yourself, and suffering on earth for an eternal reward). The protestors could relate to Jesus who was being sung of in the hymns, such as Jesus Paid It All. He was the minority in a violent government, and He suffered and died a criminal’s death, even though He was innocent. Jesus’ life was a parallel to what many black people were experiencing in the 1960s. They were innocent people suffering and dying in criminal ways. The following excerpt comes from an account of a white man who went into prison to stand in solidarity with innocent black men who were imprisoned.

Hymns also provided a sense of hope for the protestors. Songs like Keep Your Eyes on the Prize and We Shall Overcome demonstrated that they were fighting for a cause larger than themselves, and that they can remain hopeful through the struggles of the present.

While religious motivations and hopeful outlooks played a role in hymn-singing, I don’t believe these were the only reasons hymns became the unofficial anthem of the Civil Rights movement. I believe protestors chose to sing hymns because both white and black people found a home-like comfort in singing them side-by-side with fellow protestors. Both groups of people found identity within these tunes. Hymns have roots in aspects of both “white” and “black” culture. Even though these two groups brought very different experiences to the protests, both found a feeling of familiarity from singing these tunes. Amidst the tumultuous times they were living in, hymns unified the individuals’ struggle into a powerful whole.

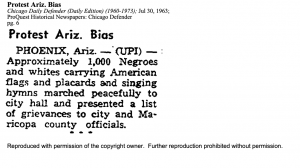

[1] “Protest Ariz. Bias.” 1963.Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Jul 30, 6. https://search.proquest.com/docview/493976140?accountid=351.

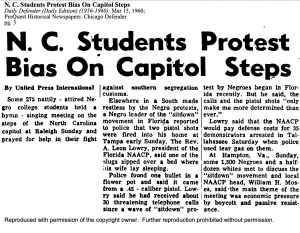

[2] “N. C. Students Protest Bias on Capitol Steps.” 1960.Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1956-1960), Mar 15, 3. https://search.proquest.com/docview/493748886?accountid=351.

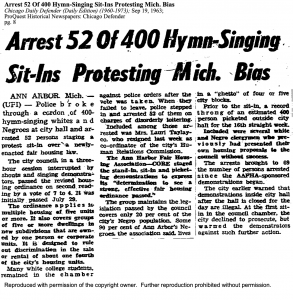

[3] “Arrest 52 of 400 Hymn-Singing Sit-Ins Protesting Mich. Bias.” 1963.Chicago Daily Defender (Daily Edition) (1960-1973), Sep 19, 8. https://search.proquest.com/docview/493990005?accountid=351.

[4] “Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) 1960-69.” Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) 1960-69, n.d.