CW: Racial slurs, suicide

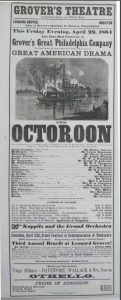

I stumbled upon this advertisement in the Afro-Americana Imprints database and immediately had about a thousand questions. Why have I never heard of this play before?  What is it about? How was this show cast? What does the title even mean? Scanning the list of characters and their descriptions set off more alarm bells as characters include “Wahnotee, an Indian,” “Pete, a Slave, an Old House Servant,” a number of judges, and more slaves. Given this list and the fact that the advertisement was published during the American civil war in 1864, I was fairly certain that if I dug in deeper I would find no end to the amount of problematic material it contained. Unfortunately, I was right.

What is it about? How was this show cast? What does the title even mean? Scanning the list of characters and their descriptions set off more alarm bells as characters include “Wahnotee, an Indian,” “Pete, a Slave, an Old House Servant,” a number of judges, and more slaves. Given this list and the fact that the advertisement was published during the American civil war in 1864, I was fairly certain that if I dug in deeper I would find no end to the amount of problematic material it contained. Unfortunately, I was right.

What is The Octoroon? The Octoroon, by Dion Boucicault, opened in 1859 at the Winter Garden Theater in New York City. The play itself was adapted from the novel The Quadroon by Thomas Reid (1856). Set in Louisiana, the conflict revolves around Zoe who is the “Octoroon,” a word that was used to describe someone who was 1/8 African, 7/8 Caucasian. (Note: Although I had never heard these terms before and they are fairly outdated,”octoroon” and “quadroon” are listed in the Racial Slur Database).

Although technically Zoe is a free woman, she is barred from marrying her (white) lover George and is pursued by the evil M’Closky. In the British conclusion the lovers are successful, but in the American version Zoe drinks poison and dies in George’s arms to prevent portraying an interracial marriage in American theaters. The play has been credited for its sympathetic view of slaves and their humanity, but Boucicault claimed that he promoted neither a specifically abolitionist or proslavery view.[1]

Was blackface used in this production? It was never explicitly stated in anything I read, but red-face was certainly used, so it can be assumed blackface was as well.

Is Octoroon still performed? The play does appear in stageagent.com and I was able to find evidence a performance in March 2013 and a movie in 1913. However, there is little else to suggest it is regularly performed although there is substantial literature in theater magazines as it relates to the changing portrayal of race on stage. The play seems to find its most relevance in an adaptation called An Octoroon by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins Soho Rep, 2014), a play within a play which examines the writing of the original Octoroon.

Although most people may not know the show now, this newspaper excerpt from an 1884 New York Globe publication states that The Octoroon is a “play very familiar with most theatre-goers.”[5]

Furthermore, it demonstrates in pervasiveness in American society since it was performed by amateurs as well as professional companies.

How does this finding connect with readings that we’ve done? I’m not going to lie, I got a little distracted from my original investigation into the use of blackface. There is so much to unpack in the play itself, and a lot of fascinating literature about it, particularly Diana Rebekkah Paulin’s 2012 book Imperfect Unions: Staging Miscegenation in US Drama and Fiction. Paulin sets out the argument that Zoe’s body acts “as a surrogate for other characters’ desires and for the intersecting racial, gender, and (trans)national ideologies informing the play.”[2] Because she is this surrogate, she can “perform dramatic and complex significations throughout the play, disrupting racial, gender, and sexual codes that govern those around her.”[3] I saw a parallel to this in Lott’s argument that blackface is tied to an obsession with black bodies. If we assume Zoe was portrayed in blackface, or at least extend this to encompass the performance of black-ness onstage, her relationship with George demonstrates a desire to control black sexuality as well as a fear of female power and autonomy.[4] Although not classified in the genre of “minstrelsy,” The Octoroon navigates similar themes as the examples outlined in Lott’s chapter.

Now what? In the end, I (understandably) left my research with infinitely more questions than I had begun. I felt like the more scholarly articles I read the less I understood. The play itself is dense and confusing to read, packed as it is with 1860s language and politics. I wasn’t even able to begin an investigation into the portrayal of Native Americans, gender, or power, and I obviously barely even touched the surface of race. Had I known that I would be leaving with more questions than answers, I might have picked a different artifact. However, even though I strayed away from music, this play and its multitude of complexities is certainly something I am interested in researching more in the future.

[1] Diana Rebekkah Paulin, Imperfect Unions: Staging Miscegenation in US Drama and Fiction, “Under the Covers of Forbidden Desire, ” University of Minnesota Press: 2012.

[2] Paulin, 9.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, “Blackface and Blackness: The Minstrel Show in American Culture,” Oxford University Press: New York. 1993.

[5] “Performance of ‘The Octoroon.’” New York Globe. New York: 28 June 1884.

Works Cited

“[Playbill. 1864-04-22].” Afro-Americana Imprints. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/iw-search/we/Evans/?p_product=EAIX&p_theme=eai&p_nbid=D4DP55RKMTU2OTk3ODg5NC41NjczNTg6MToxMzoxOTkuOTEuMTgwLjkw&p_action=doc&p_docnum=1&p_queryname=3&p_docref=v2:13D59FCC0F7F54B8@EAIX-154E9B34E025DFA8@S983-@1.

Lott, Eric. Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. “Blackface and Blackness: The Minstrel Show in American Culture.” Oxford University Press: New York. 1993.

Paulin, Diana Rebekkah. Imperfect Unions: Staging Miscegenation in US Drama and Fiction, “Under the Covers of Forbidden Desire. ” University of Minnesota Press: 2012.

“Performance of ‘The Octoroon.’” New York Globe. New York: 28 June 1884. African American Newspapers.