Over the course of these blog posts, my classmates and I have discussed an enormous range of subjects and, for the most part, usually tried to connect them back to race and identity in American music – the topic of the course. However, this week, I have decided to stray from said topic into something a little lighter: A composer renowned for his ideas about tonality that were later lauded as incredibly forward-thinking and were vital in forging an American modernist identity. A man whose music was written almost entirely for himself and close friends and then (figuratively) left in his desk for future musicians to discover. A figure who thought that classical music as he knew it was overly refined, feminine, and therefore emasculated. If you hadn’t figured it out already, today I will be talking about none other than Charles Ives. More specifically, I will be talking about Charles Ives’s correspondence1 with his fiance and eventual wife, Harmony Twitchell.

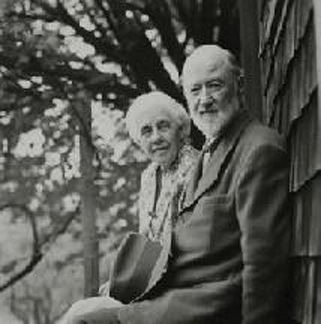

Charles Ives and Harmony Twitchell

I miss you all the time & feel how rich I was when I had you last week – to hear your voice & put my hand & feel you – never mind. I have your love and that is everything after all – I was quite wrong when I said that it was a year ago that I knew I loved you[.] It’s been all the time just the same but I never said it right out to myself until a year ago & gloried & rejoiced in it…

Harmony

How endearing! It can be so easy to forget the humanity of historic figures, (and modern day ones as well) but the act of reading someone’s correspondence with a loved one is one of the easiest ways to avoid such selective amnesia. In the blink of an eye, Ives goes from being a one-dimensional curmudgeon, to something a little more complex, a little more human. And that makes all the difference.

1 Ives, Owens, and Owens, Thomas Clarke. Selected Correspondence of Charles Ives. Roth Family Foundation Music in America Imprint. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.