Who gets to decide the name of a genre? Should the artist or the consumers? The managers or the publishers? This question has constantly bothered me as we have looked at the racial influences put upon the blues and the traditions that have grown out of it. As jazz came out of the blues and bebop came out of jazz, the story of a genre’s name always tends to tell me a lot about its birth.

Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie are generally thought to have been the founding fathers of bebop. However, a competing theory is that Thelonious Monk deserves a majority of the credit for the music we know today as bebop. Considering that this month marks Monk’s centennial, I think that the Monk-centered theory deserves more examination.

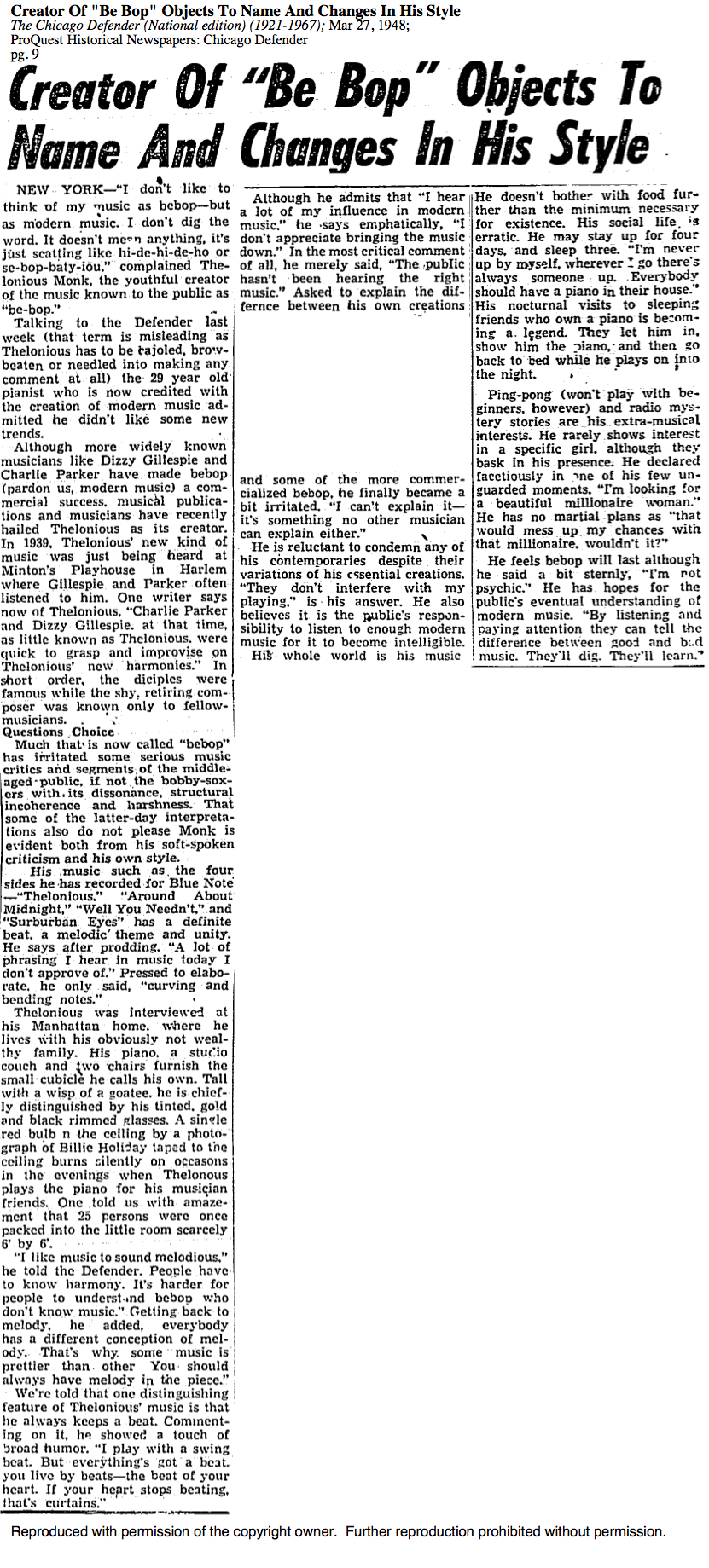

A notable article in The Chicago  Defender on March 27, 1948 is titled “Creator Of “Be Bop” Objects To Name And Changes In His Style.” Already this Monk-centered theory is sounding fairly authoritative. In the article, Monk is set in opposition to Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, and it starts out by a quote from Monk saying,

Defender on March 27, 1948 is titled “Creator Of “Be Bop” Objects To Name And Changes In His Style.” Already this Monk-centered theory is sounding fairly authoritative. In the article, Monk is set in opposition to Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker, and it starts out by a quote from Monk saying,

“I don’t like to think of my music as bebop-but as modern music. I don’t dig the word. It doesn’t mean anything, [Be Bop] is just scatting.”

I think Monk is trying to get people to understand how much thought and intention goes into his music. He wants to avoid any chance that his music might be written off as nonsense. Monk goes on to say that

“I like music to sound melodious. People have to know harmony. It’s harder for people to understand bebop who don’t know music… You should always have melody in the piece,”

which, to me, further asserts that Monk’s music has a certain intelligence behind it. Of course, if Monk’s “modern music” really became widely known as “bebop,” then what happened?

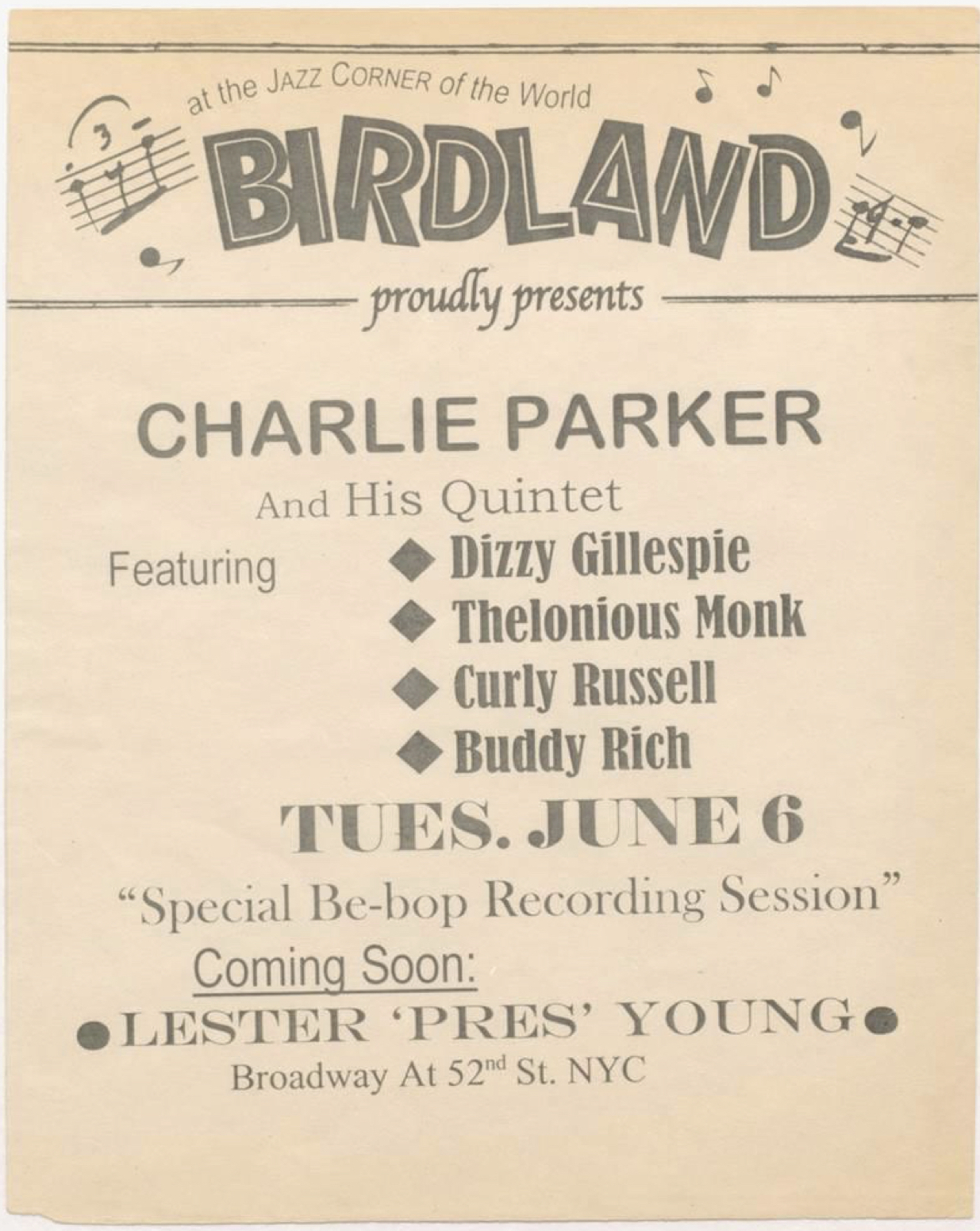

Just 2 years later, in 1950, Monk’s name appears on this poster. He is clearly under Charlie and Dizzy’s influence by then. Bebop appears in the poster, and it is certainly not his name in the biggest font. So what happened? Well, one of Monk’s biographers, Robin D. G. Kelly, says in an interview with The Atlantic that Monk lost his cabaret card during this period; this was one of the major influences leading to Monk’s loss of prominence. Kelly says that this period was called “the ‘un- years,’ when Monk had lost his cabaret card and could not play in nightclubs that served alcohol—which was pretty much all of them” (Gorney).

Just 2 years later, in 1950, Monk’s name appears on this poster. He is clearly under Charlie and Dizzy’s influence by then. Bebop appears in the poster, and it is certainly not his name in the biggest font. So what happened? Well, one of Monk’s biographers, Robin D. G. Kelly, says in an interview with The Atlantic that Monk lost his cabaret card during this period; this was one of the major influences leading to Monk’s loss of prominence. Kelly says that this period was called “the ‘un- years,’ when Monk had lost his cabaret card and could not play in nightclubs that served alcohol—which was pretty much all of them” (Gorney).

Could this really have affected Monk that much? I looked into the history of cabaret cards for my answer. As it turns out,

The cabaret card could be revoked at the whim of the police, usually for narcotics infractions, however slight or untried… As an embodiment of the institutional distrust stirred up by jazz musicians, especially African-Americans, [the cabaret card is] a key to our understanding of the odds those musicians faced in civil society” (Chinen).

I suppose that I am thankful that Monk was still able to work with giants like Parker and Gillespie. However, I have to wonder what would have come to the genre of bebop if Monk has stayed in prominence from 1948-1950 and had been able to push his idea of what “modern music” should have been. To honor Monk and what modern music could have been, I have put together a Spotify playlist with the first 4 blue note singles recorded by Monk.

These singles were cited in The Chicago Defender article as a hallmark of Monk’s “modern music” style. If you have heard these songs before, I hope you are able to listen to them now with a slightly different perspective. If you have never heard them before, I also beg you to listen to them… because they are simply really good and intelligent music.

-Brock Carlson

Works Cited

Creator Of “Be Bop” Objects To Name And Changes In His Style. (1948, March 27), Chicago Defender. Retrieved from ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Defender

Chinen, N. (n.d.). The Cabaret Card and Jazz. Retrieved October 16, 2017, from https://jazztimes.com/columns/the-gig/the-cabaret-card-and-jazz/