In Ava DuVernay’s 2014 film “Selma”, poetic license is taken in depicting the role gospel singer Mahalia Jackson played in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery voting rights marches. During a moment of doubt, Martin Luther King Jr. (played by David Oyelowo) phones Jackson (portrayed by R&B singer Ledisi) and asks her to share “the Lord’s voice” with him. She answers by singing the immortal gospel classic, “Take My Hand, Precious Lord”. This song was a standard at prayer meetings and Civil Rights marches, and was even performed by Jackson at King’s funeral. It was her showstopper, and the song that was requested the most from her by both King and her audiences worldwide.

At the 57th Annual Grammy Awards on February 8th, 2015, the song was performed as a prelude to a “Selma tribute”, which featured R&B artist John Legend and rapper Common performing their Academy Award Winning Song from the film titled “Glory”. However, the song was performed not by Ledisi but by the undisputed modern queen of R&B: the one and only Beyoncé.

This inspiring and powerful performance elicited wide acclaim, though some were quick to point out that a true tribute would have featured Ledisi (who was in attendance), rather than Queen Bey. Criticism escalated when it became apparent that Beyoncé herself had approached Legend and Common about performing the song, as it wasn’t originally planned to be part of the show. However, amid the accusations of self-promotion and concerns over unfair exclusion, the opportunity for an discussion regarding style was unfortunately missed.

On one hand it is easy to criticize Beyoncé’s performance if we are comparing to the historical standard set by Jackson. It is fair to say that Ledisi followed this standard in preparing for “Selma”, mimicking some of Jackson’s techniques and melodic alterations. (The album the below performance is taken from is available in the St.Olaf Music Library, call number M2198.J3 M3 [v.1])

For live video performances by Jackson, check out https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z0a8RNdnhNo; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=as1rsZenwNc

Whereas Jackson displays virtuosity in the emotional range of her voice, Beyoncé relies more on virtuosic vocal runs more akin to flashy pop music than to a traditional gospel style. The spiritual component of Jackson’s version is amplified by the seemingly extemporaneous approach to the melody by Jackson and the fluid approach to the harmonic changes by her pianist and organist. Contrastingly, aspects of Beyoncé’s version seem meticulously rehearsed, from the timing her background singers movements to her rather parodic head movements at about 2:10.

But I think the biggest discrepancy between Jackson and Beyoncé’s performance is a matter of visual and emotional, rather than musical, aesthetics. In the live performances posted above, Jackson stands alone in the middle of the barren stage, barely moving but to look up to the sky. As the text suggests, she is powerless and none but God can help her in her time of trial. Beyoncé could not be more different, not only in complete control of her own body but seemingly in control of the 12 men behind her. She even cuts off the organ at the end! While this powerful depiction of an African-American woman is inspiring, it undeniably draws away from the meaning of the song, especially in conjunction with the accusation that this was more promotional stunt than impassioned performance. When Jackson performed, she would humbly tell the audience “I’m so happy for the way you are receiving me. I love applause. But you know I’m a gospel singer and I like to hear a few ‘amens’. ” [1]

That isn’t to say that any of this is bad, or that Ledisi would have performed any better or differently than Beyoncé. No one can or should deny how impressive and moving this performance is. Ledisi herself defended Beyoncé better than anyone.

“The song, ‘Take My Hand, Precious Lord,’ has been going on forever. It started with the queen, Mahalia. The Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin (who sang the song at Jackson’s funeral, in 1972). Then I was able to portray and sing my version of the song. And now we have Beyonce. I’m a part of history. Look at it like that, instead of looking at it as a negative. To me it’s a great, great honor to be a part of a legacy of a great song, by Thomas Dorsey.” [2]

To this point, performances by Franklin and Whitney Houston are much more radical and pop-infused than those of Jackson and Ledisi, which arguably stay truer to recorded performances by Dorsey. But perhaps this development is a good thing. The ability of musicians (and more importantly, African-American women) to freely influence this song is a great thing, and stands for what Jackson herself fought and sang for. Dr.Benjamin Mays elegy for Jackson said it best:

“One can only hope that this great and good woman will never die but that her life will inspire so many young people that she will live on throughout eternity. In this way she will become immortal.” [3]

He may as well have been speaking of the song too.

[1] Duckett, Alfred. “Mahalia Jackson Like Applause (Beg Pardon) Amens at Concerts.” The Chicago Defender (National Edition) (1921-1967), Jun 01, 1957. http://search.proquest.com/docview/492918933?accountid=351.

[2] Fensterstock, Allison. “Grammys 2015: Beyonce takes on Mahalia Jackson, and Ledisi has a perfect response.” The Times-Picayune, Feb 08, 2015. http://www.nola.com/music/index.ssf/2015/02/grammys_2015_beyonce_takes_on.html

[3] Mays, Benjamin E. “Reminiscing about Mahalia Jackson.” Chicago Daily Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1966-1973), Feb 26, 1972. http://search.proquest.com/docview/493504320?accountid=351.

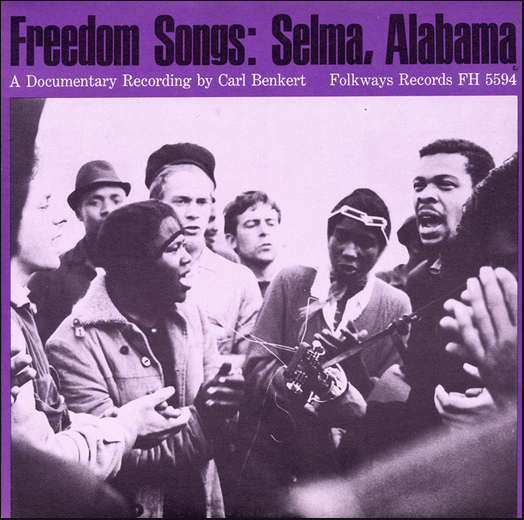

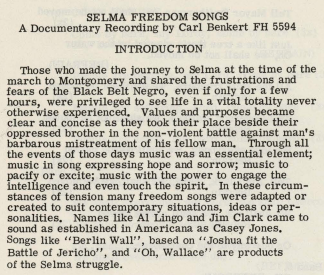

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.”

unique collection of recordings in their Smithsonian Folkways collection called “Freedom Songs: Selma, Alabama” which capture the emotional content of the march. Referred to as a “Documentary Recording,” Carl Benkert set out to preserve this moment in our nation’s history through sound. The liner notes confirm that “through all the events of those days, music was an essential element” and that the music expressed “hope and sorrow” while being able to “excite and pacify.” article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>

article even specifically states that the police arrested “hymn-singing Negroes.”sup>