Music is often touted as a vehicle for social justice; a means of liberation, but it can just as easily be utilized as a means of control and oppression. Modern popular music has often aimed to push against the status quo, from Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth” to Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power”, but from an educational standpoint, there is power in deciding what music is studied and what is omitted.

This power is primely exhibited in the curriculum of the Carlisle Indian School. Opened in 1879, the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was the first boarding school for Native American children to be both funded and ran by the U.S. government1. Its doors were open for nearly 40 years and saw over 1,000 students enter and graduate. The term “boarding school” is almost comical to use, as the main objective of the school was the forced cultural erasure and assimilation of Native students.

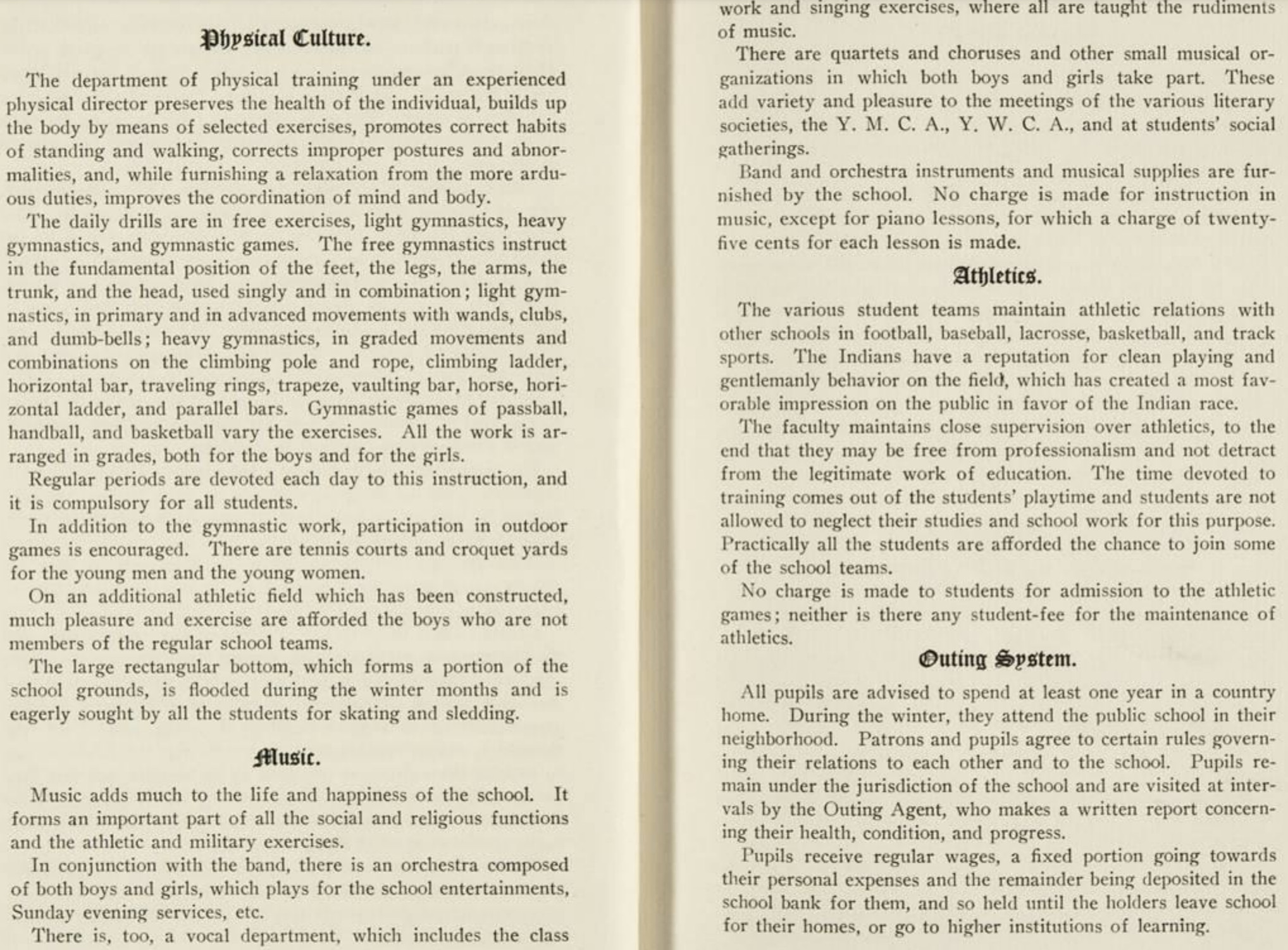

Carlisle Indian Industrial School. 1915. Catalogue and synopsis of courses, United States Indian School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Carlisle: Carlisle Indian Press. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_389_C2_C2_1915 [Accessed October 25, 2023].

Seen above is an excerpt from the course catalogue of the Carlisle school. The language parades the importance of music in regards to the development of students, upon further reading, it is abundantly clear what kind of music they are referring to: American music. To the administration, and by extension the American government, Native music was seen as illegitimate. Students instead were to sing in choir, play in the band, or play in the orchestra. American music, in this scenario, was used as a means of cultural cleansing; of oppression.

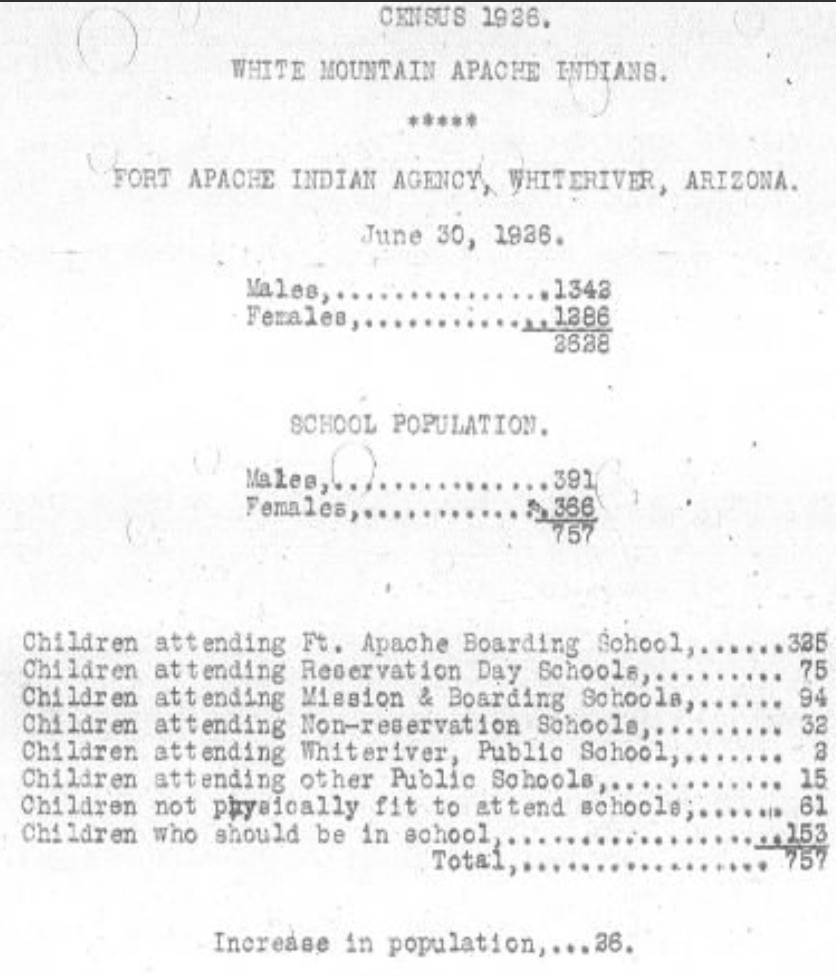

The National Archives. US, Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940. 1967. Courtesy of Native American Archives. https://www.fold3.com/image/216096302/1924?terms=schools,boarding,united,america,states,school

This form of indoctrination highlights how the powers that be are able to exert control by deciding what is music and what isn’t, or what is high art art and what isn’t. As Cloonan and Johnson argue in “Killing Me Softly with His Song”, “Every time we applaud the deployment of music as a way of articulating physical, cognitive and cultural territory, we are also applauding the potential or actual displacement or even destruction of other identities”2.

1Carlisle Indian School Project. n.d. “Carlisle Indian School Project | Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project. https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/.

2Cloonan, Martin, and Bruce Johnson. “Killing Me Softly with His Song: an Initial Investigation into the Use of Popular Music as a Tool of Oppression.” Popular Music 21, no. 1 (2002): 27–39. doi:10.1017/S0261143002002027.

Works Cited

Carlisle Indian Industrial School. 1915. Catalogue and synopsis of courses, United States Indian School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Carlisle: Carlisle Indian Press. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_389_C2_C2_1915 [Accessed October 25, 2023].

Carlisle Indian School Project. n.d. “Carlisle Indian School Project | Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project. https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/.

The National Archives. US, Indian Census Rolls, 1885-1940. 1967. Courtesy of Native American Archives. https://www.fold3.com/image/216096302/1924?terms=schools,boarding,united,america,states,school

Cloonan, Martin, and Bruce Johnson. “Killing Me Softly with His Song: an Initial Investigation into the Use of Popular Music as a Tool of Oppression.” Popular Music 21, no. 1 (2002): 27–39. doi:10.1017/S0261143002002027.