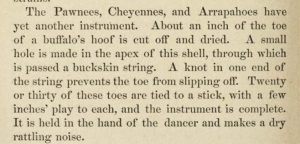

If you look at transcriptions of Native American music created by musicologists in the early 20th century, a common pattern emerges. Densmore’s writings are filled with transcriptions that feature several different odd time signatures back to back, hanging 32nd notes, and other abominations, all in an attempt to most accurately depict native music. Forcing Native American music to conform to western notation is an act of violent colonialism. Though not apparent, this is an act that attempts to create forced assimilation of native culture to Anglo-Saxon American culture.

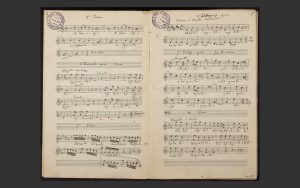

While this was going on, America’s neighbors to the north were doing something similar, but in a completely different way. Emile Petitot, a French priest, was transcribing the songs of nations in the northwest of Canada. Petitot’s approach was vastly different from that of Densmore. As you’ll see below, in the seven transcriptions Petitot did, he makes no attempt at describing the music using the usual spaghetti monsters seen in Densmore’s work.1 Instead, his transcriptions are made of note values and time signatures regularly seen in western music: Common time, cut time, quarter and eighth notes with the occasional use of triplets.

Petitot, Father, Emile. 1862-1889. Chants indiens du Canada Nord-Ouest [manuscript]: recueillis, classés et notés par Emile Petitot, prêtre missionnaire au Mackenzie, de 1862-1882, 1889. [Manuscript]. At: Place: The Newberry Library. VAULT box Ayer MS 715. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_MS_715 [Accessed October 26, 2023].

On the other hand, it’s very easy to see how this transcription is much worse. At least Densmore poured time and effort to try to accurately depict the music as it was; this transcription erases every part of the music that doesn’t conform to western music standards. I could see these transcriptions being lazy attempts without any care for the music being represented. I tend to believe that these transcriptions are even worse. Densmore’s transcriptions are “violent notation,” but at least she actually tried.