Carson City. A sleepy small town in the Eagle Valley of Nevada. Surrounded by brown hills and the mighty Sierra Nevada to the West, the town seems even smaller. In Nevada it is common to spray paint the hills with the letter of the local high schools. In Carson City there is only one public high school, Carson High, and looking to the west you can see a giant C on the hill – we call this C hill. But if you look to the east, you’ll see another letter spray painted on the hill – S hill. But S hill is not the site of high school teenagers yearly pranks and shenanigans like C hill is. It’s a remembrance. A remembrance of the residential boarding school that operated in Carson City for over 90 years.

Stewart Indian School, also known in its history as Carson Indian School or Carson Institute, was built as part of the assimilationist era policies of the late 19th century that forcibly removed Native children from their families to be trained at residential schools. The school opened in 1890, first taking students from the local Washoe, Paiute, and Western Shoshone tribes, but later expanding to take students from all across the Western United States.

This snapshot is from the Board of Indian Commissioners Bulletin No. 34 in 1917, and is representative of the white savior complex that was common at the time and associated with Stewart

There is a lot that can be said about residential schools and about Stewart in general, such as the way white people viewed and operated the school, the drastic differences in experience of students across the school’s 90 years of operation, and the historical trauma and reclaiming of the space by the Nevada Indian Commission today. I encourage you to learn more at their website. But for the purposes of this blog, I’m going to focus on one element of the school – the band.

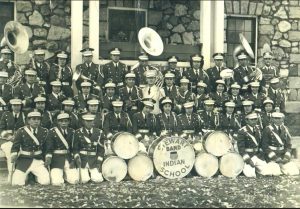

Considering Stewart’s legacy of forced assimilation and the punishment of students’ cultural heritage (like language, music, and traditions), I expected to be writing a post about how the school’s band was just another tool of assimilation and erasure. But while it was undoubtedly part of that same structure of assimilation and cultural violence, my research led me to view the Stewart band’s legacy as more complex than just that.

Since documentation was much harder to find for the earlier years of operation, I’m focusing on the last 40 or so years of operation, from the 1940s to 1980. Looking through many school yearbooks from this era, I found that the band was always featured prominently. It had at least it’s own page and often many pictures, sometimes accompanied by a description of the band’s accomplishments. The band was public facing, competing at competitions, performing at the Nevada Day Parade, and giving public concerts. I managed to find an aural resource, a description from the son of former band director Earl Laird (director from 1930-1939) which described Laird as a beloved teacher, and an interview clip of an alumnus of the band from the 1940s who described playing in the Nevada Day Parade as “the biggest highlight”.

Since documentation was much harder to find for the earlier years of operation, I’m focusing on the last 40 or so years of operation, from the 1940s to 1980. Looking through many school yearbooks from this era, I found that the band was always featured prominently. It had at least it’s own page and often many pictures, sometimes accompanied by a description of the band’s accomplishments. The band was public facing, competing at competitions, performing at the Nevada Day Parade, and giving public concerts. I managed to find an aural resource, a description from the son of former band director Earl Laird (director from 1930-1939) which described Laird as a beloved teacher, and an interview clip of an alumnus of the band from the 1940s who described playing in the Nevada Day Parade as “the biggest highlight”.

Based on my preliminary research in the yearbook archives and the audio recording, my impression is that the band was important to the students, at least in the later years of operation. So despite being part of an institution of forced assimilation and being inextricably linked to this horrible legacy, perhaps within the context of the school itself the band offered some sort of relief. More research is necessary to fully understand the Stewart band, but one thing is certain – it has a complex legacy.

Bibliography

“Stewart Indian School Trail Map.” Stewart Indian School, https://stewartindianschool.com/walking-trail/.