Claims to justify the inferiority of the black race often sought evidence from science, as seen in the article below from The Musical Visitor in 1895. According to the short announcement, biological differences in black people prohibit their ability to sing European art music and sound like white people as well as their ability to play an instrument.

In contrast, we know of a few African American concert singers during the 19th century who toured and had classical musical training.[1] 120 years later, here is Leontyne Price, just to help clear up that misconception as well. What scholars have suggested then, is that African American concert singers chose not to sing like a white person because they couldn’t make any money singing that way in the racist show business world, and furthermore people wanted to hear the African voice.

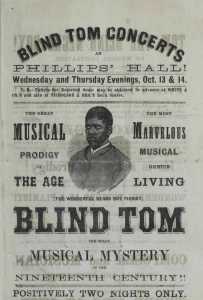

Perhaps the most appalling part of the article however explains that black people cannot help imitating the white man’s music and “the race instinct in the negro does not incline toward persistency of purpose” that it takes to play a musical instrument. 35 years prior to this, a young man named Thomas Bethune provides period proof against these scientific misconceptions. Blind Tom was born a blind slave, but by the age of four, showed great interest in the piano and great talent in imitating the sounds he heard, spending many hours a day learning the piano by ear. Tom’s master then paid the best musicians to come play for Tom so that he could imitate them, therefore gaining a fairly high musical education. Blind Tom’s case may be unique because of what his blind condition allowed him to achieve (namely, not doing slave labor), but there is no question that hard work and training went into Tom’s musical genius, not just talent. His international fame as a musical genius and his many compositions are evidence enough to debunk hypotheses such as the one in the above article, yet conceptions about the inferiority of black musicians persisted.

To add another layer of complexity in this story, Tom’s master, General James Bethune, hired him out to tour all over the country, earning the Bethune family and his managers approximately $3,000 per month during his performance career. Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Tom was a slave to his performance managers and master, not receiving a penny of the touring profits. Articles advertising his performance raved about his ability to improvise and play multiple tunes at once, but also portrayed him as an exhibit, often referring to him as “it” or “the idiot” and described with barbaric features.[2] In other words, Tom’s talent and hard work did not prove the musical potential and value of African Americans as humans, rather is evidence to show that white people became interested in black musicians and black music when they could make money from it and when they could control it.

[1] Sonja Gable-Wilson, “Let Freedom Sing! Four African-American Concert Singers in Nineteenth Century America.,” Doctorate Thesis, University of Florida, 2005.

[2] Geneva Handy Southall, Blind Tom, the Black Pianist-Composer Continually Enslaved, Lanham, Maryland: Scarcrow Press, Inc. 1999.

[3] “NEGRO MUSIC,” The Musical Visitor, a Magazine of Musical Literature and Music (1883-1897) 24, no. 7 (07, 1895): 179. http://search.proquest.com/docview/137505026?accountid=351.