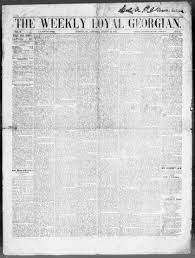

The newspaper headline proudly reads “Evanti Wins Plaudits of Italians”, published in the Wyandotte Echo in Kansas City. At first glance, there is nothing particularly strange about this headline besides the fact that a Kansas City newspaper is paying mind at all to the opinions of Italians on, well, anything. But there’s so much more to it. It is true that Evanti had won the favor of many Italians, as well as plenty of others throughout Europe, but it is important to acknowledge that the reason she was really in Europe at all was for the sake that her talents were not being adequately appreciated in America. The fact that a newspaper in Kansas City would sing her praises years after she essentially gave up on a music career in America is ironic, but in a way also demonstrates the impact Lillian Evanti had and her importance to other members of the black musical community.

In her early years, Evanti performed mainly in DC, but it’s in her plea to the Crisis newspaper that we can really see how difficult that was. In her letter to W.E.B Du Bois that he ended up publishing in the newspaper, it is clear that segregation was taking its toll on her platform and audience. It was then that she decided to go to Europe (which mind you, was not known for being terribly anti-racist in the 1920s either) and proceeded to stun endless audiences with her voice. Why then, when America had all but shunned her, did the Wyandotte Echo decide to publish this piece? This newspaper, unlike the Crisis was not known for lifting up BIPOC voices, but perhaps we could attribute this all to the fact that the American obsession with fame is a very powerful thing.

Akin to the French obsession with jazz, it is likely that having an American singer become so renowned abroad was a huge deal for America. Before the 1920s, there were very limited defining factors in terms of American sound and a small number of renowned classical performers or composers. Evanti would have been extraordinary for this sake alone. Still, it is almost cruel that anyone should love her for her fame when she was so hated for her race. Nonetheless, there is something to be said for the fact that she had such a positive presence in a newspaper at all for this time period. It is possible that she opened doors for other black musicians by breaking down some of the barriers she had faced as a black woman in America by going to and finding fame in Europe.

Sources

- “Evanti Wins Plaudits of Italians.” Wyandotte Echo (Kansas City, Kansas) III, no. 11, June 6, 1930: PAGE [ONE]. Readex: African American Newspapers. https://infoweb.newsbank.com/apps/readex/doc?p=EANAAA&docref=image/v2%3A12ACD97C8656DCF8%40EANAAA-12C8BA26840196C8%402426134-12C8BA268E28EC78%400-12C8BA26BB913CB0%40Evanti%2BWins%2BPlaudits%2Bof%2BItalians.

Crisis (Firm). “Pages from The Crisis with editorial by Lillian Evanti, 1927.” W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312). Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/pageturn/mums312-b175-i625/#page/1/mode/1up