Let’s talk about the Ghost Dance.

The Ghost Dance began as the result of a series of visions by a Paiute elder around 1869 that the Earth would experience healing and the Paiute people would receive help. Twenty years later, another Paiute leader had visions of land being restored to all native people, and Europeans leaving native people alone. He believed that this dance would help his visions become reality. Representatives from different tribes came to hear from this Paiute leader, causing the Ghost Dance to spread, evolve, and be performed as a means of peaceful protest in different native languages1.

(I tried embedding recordings of the Ghost Dance, but was unsuccessful, so you can listen here.2)

But naturally, when white people learned about the spread of this dance across different native groups and the meaning behind the dance, they felt threatened.

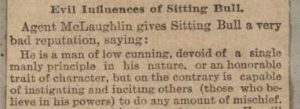

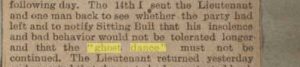

An article published on Oct. 28, 1890 in the Chicago Tribune, found through the American Indian Histories and Cultures database, illustrates the fear that white people were trying to stir up about the Ghost Dance. The article begins by discussing the visions that led to the dance, saying of the visions, “they promise… that the white man will be annihilated and the Indian restored to his former power and prestige”. The article then goes on to describe the “Evil Influences of Sitting Bull”, a Lakota chief in South Dakota. The article quotes Agent James McLaughlin, a US Indian Service Agent, who says of Sitting Bull, “He is a man of low cunning, devoid of a single manly principle in his nature, or an honorable trait of character”. The article also informs readers that McLaughlin sent a Lieutenant to tell Sitting Bull “that his insolence and bad behavior would not be tolerated longer and that the ‘ghost dance’ must not be continued.” Sitting Bull told the Lieutenant “that he was determined to continue the ghost dance”, since the Great Spirit said they must do so. McLaughlin seemed determined that he could change Sitting Bull’s mind3.

On Dec. 15th, 1890, less than two months later, when police came to put an end to the Ghost Dance ceremony, Sitting Bull disagreed and was killed. Between 150 and 300 Lakota men, women, and children who tried to escape to safety were killed in what is known now as the Wounded Knee Massacre, but referenced in many outdated history books as “The Battle of Wounded Knee”. The U.S. soldiers who killed Lakota men, women, and children received the Congressional Medal of Honor4.

All of this violence occurred over what? A dance. A dance that seems to have been effectively smothered over time, as I could not find any sources of it still being performed today.

What can we learn from this? We can learn to be wary of news sources which describe people or cultural practices in heightened, emotional language. We can learn to ask ourselves when we feel threatened, and why. We can learn to ask what musical practices we have suppressed in the past because they made us uncomfortable, and what musical practices we suppress today.

Footnotes

1 Hall, Stephanie. “James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs, 1894.” James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs, 1894 | Folklife Today, 17 Nov. 2017, https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2017/11/james-mooney-recordings-ghost-dance-songs/.

2 Mooney, James, and Smithsonian Institution. Bureau Of Ethnology. James Mooney recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance songs. [Washington, D.C.: E. Berliner, 1894] Audio. https://www.loc.gov/item/2014655251/.

3 Parker, Ely Samuel (1828-1895). 1828-1894. Ely Samuel Parker scrapbooks: Vol 10. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, American Indian Histories and Cultures, http://www.aihc.amdigital.co.uk/Documents/Details/Ayer_Modern_MS_Parker_VL10 [Accessed November 01, 2021].

4 Hall, Stephanie. “James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs, 1894.” James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs, 1894 | Folklife Today, 17 Nov. 2017, https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2017/11/james-mooney-recordings-ghost-dance-songs/.