After our last class, I have been thinking about how early scholars of Indigenous music (like Frances Densmore) often come from outside of the Indigenous community. Densmore and others often receive praise for recording Indigenous music in a white savior sort of way. I found Emile Petitot’s transcription of Indigenous chants in what is now called Mackenzie, British Columbia, Canada. I was curious about who Petitot was, his relationship with the Indigenous tribes he studied, and what he sought to accomplish.

Petitot was a Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate, part of the Catholic Church, who left France for a 12-year mission.1 He was primarily interested in geography and ethnography of the regions he studied and wrote several books on translations of tribal languages to French, his visit to the Tchiglit Inuit, and cultural traditions of a half dozen other tribes.2

However, his reflections and his legacy reflect his white supremacist beliefs. One article lauds Petitot for

“Attending to the physical, as well as spiritual, well-being of the Indians. Petitot nursed them when they were sick, and supplied them with necessary food and clothing.”3

I have a hard time believing this account of his behavior. White historians who study Indigenous culture are often praised for doing the bare minimum. Furthermore, after observing Chippewa Indians under the influence of alcohol, Petitot concluded that

“whiskey would be the white man’s best means for completely exterminating the Indian population.”4

This statement reminiscing about the extinction of Indigenous people reveals white supremacist motives for “studying” Indigenous people.

With a more nuanced understanding of his motives, I was curious how his observations compared to other scholars of Indigenous performances. His white supremacist motives and emphasis on transcription are similar to Frances Densmore’s (see Anna Severtson’s post for more on Densmore’s as a well-meaning white woman).

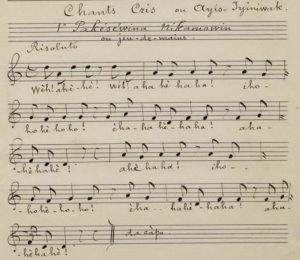

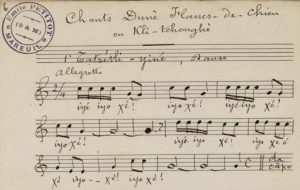

Petitot’s transcriptions in this document, like Densmore’s, contain Western classical notation, including time signatures, key signatures, and tempo and articulation markings. Petitot’s notes are in French, but he wrote the performance texts in the Indigenous languages. Still, presenting Indigenous performances in a Western classical notation style clarifies that Petitot wrote for European music scholars, not for those interested in Indigenous culture.

A more accurate representation of Northern Plains Indians performances comes from Tara Browner. She observed that many Northern Plains songs have high male voices, jagged melodies, and short phrases.5 Making assumptions about phrasing is difficult without recordings. Still, many of the chants that Petitot transcribed had jagged melodies and would be high in a male voice. However, this only shows that Petitot’s findings match a general description of a regional sound.

Music scholars must think critically when studying performances of other cultures. Analyzing Petitot’s colonial-settler mindset helps us understand his motives, which we must consider when reading his transcriptions of Indigenous songs. Unfortunately, his white supremacist motives and his reception as a white scholar of Indigenous study are not unique. Recognizing this reality should compel musicologists to do better work moving forward.

Footnotes

1 Donat Savoie, “Emile Petitot (1838-1916),” Arctic 35, no. 3 (1982): 446.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 John J. Honigmann, “Emile Fortuné Stanislas Joseph Petitot,” Encyclopedia Artica, 1951, para. 3, accessed October 31, 2021, https://collections.dartmouth.edu/arctica-beta/html/EA15-56.html.

5 Tara Browner, ed., Music of the First Nations: Tradition and Innovation in Native North America, Music in American life (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2009), 138.

Bibliography