This week, I came three Christian hymns translated into some indigenous languages of the Northwest coast. One of these, a Chinookan language, is spoken by the Chinook people whose native lands are in what is now called Washington and Oregon (Britannica). The Chinook people have their own spiritual practices that emphasize the powers of nature, but many of them were forced or coerced into Christianity by white missionaries (The American History). This forced Christianization often took place at residential schools where children were forced to abandon their Native culture and assimilate to European cultural norms. Besides the trauma of being separated from their culture, these children were often subject to other kinds of horrific abuse (Hanson).

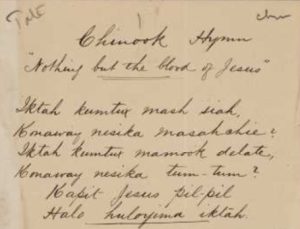

The hymn pictured below was translated into Chinook in 1892 by Charles Montgomery Tate, a Methodist minister who ran such a school (The Children Remembered). The hymn is a verse and chorus of “Nothing but the blood of Jesus” (Tate).

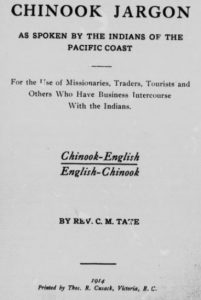

I think it is puzzling to find hymns that have been translated into the languages of indigenous peoples, because the ultimate goal of ministers like Charles Montgomery Tate was to assimilate Native Americans into white Christian culture, robbing them of their traditions and even their languages; the Chinookan languages are in danger of extinction, with all of the native speakers of the languages deceased, and very few speakers left at all (Vachter). But in addition to his conversion efforts, Tate also did a lot of work in translating indigenous languages, for example, the Chinookan to English dictionary pictured below (Tate).

I think it is puzzling to find hymns that have been translated into the languages of indigenous peoples, because the ultimate goal of ministers like Charles Montgomery Tate was to assimilate Native Americans into white Christian culture, robbing them of their traditions and even their languages; the Chinookan languages are in danger of extinction, with all of the native speakers of the languages deceased, and very few speakers left at all (Vachter). But in addition to his conversion efforts, Tate also did a lot of work in translating indigenous languages, for example, the Chinookan to English dictionary pictured below (Tate).

What is sad is that some of the only written evidence of how Chinookan languages might have sounded in the past was written by the very people who sought to rob Chinook people of their language and culture. Unfortunately, it is often the case that those in power are the ones who write history; as we have discussed in class, much of the written evidence of how early African American music sounded was written by white slaveholders. As musicologists and historians, it is important to recognize that the primary sources that are left over often leave out the voices most suited to speak to musical and linguistic traditions: the practitioners of those traditions themselves.