Spirituals are a popular topic for discussion in vocal music because they bring about many questions to consider. The genre was created by black enslaved people and later notated and arranged by various composers. However, their origins make us pause to consider whether or not predominately white ensembles or vocalists should be allowed to perform these works. I think the general consensus on the subject is “yes, but…”. Conductors should be careful not to tokenize the spiritual in their repertoire for the night, perform it last as is often the case, provide informative program notes about every piece, and they should ensure the song is sung appropriately. There are many more things to say about this subject, however, you get the picture. Likewise, I would argue, and I think most would agree, that while we should perform spirituals by black composers, performing spirituals arranged by white composers is highly problematic. Lily Strickland is one such white composer from South Carolina, and the song in question today is “Dah’s Gwinter Be Er Lan’slide”.

Strickland was born in South Carolina in 1884 and died in 1958. She wrote many songs ‘inspired by her southern upbringing and black spirituals and dialect and then her later music reflected her experiences in the continents of Asia and Africa and also wrote works imitating songs of indigenous people. She was wildly successful and her works were played by famous ensembles including the Metropolitan Opera and the New York Philharmonic. Furthermore, Melissa Walker, a writer for the South Carolina encyclopedia claims that Strickland wanted to rebel against cultural norms for women in the South1. Arguably, Strickland’s work and success were highly unusual for a female composer in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and so it is really hard as a feminist to face the fact that most of her music plays into harmful practices of cultural appropriation, especially pertaining to her numerous papers on Asia which perpetuate orientalism that I came across while searching through the St Olaf library. Therefore, celebrating or performing her work seems impossible and highly problematic today with our modern lens.

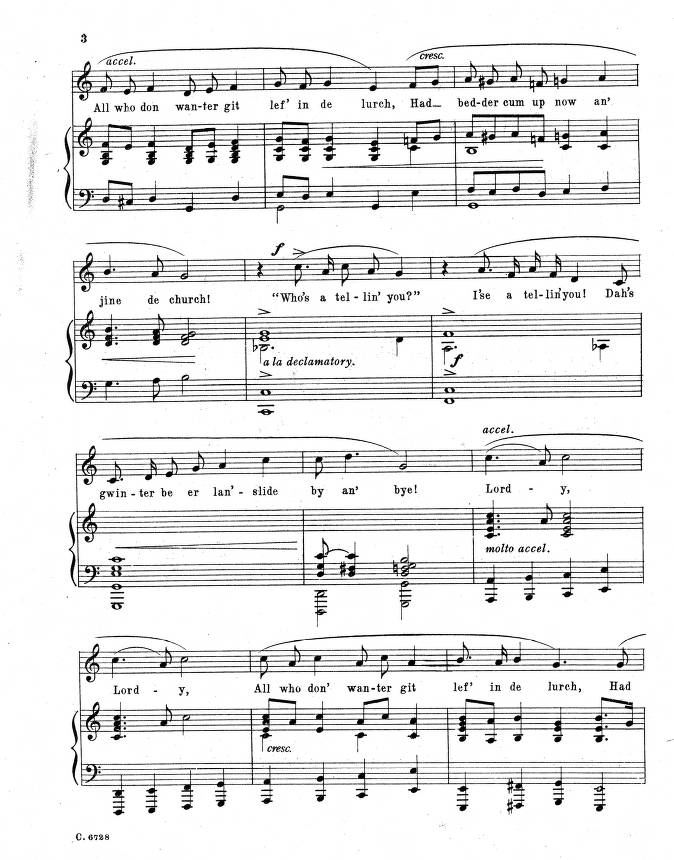

One of her pieces I stumbled across on the Sheet Music Consortium database is the aforementioned “Dah’s Gwinter Be Er Lan’slide”. This song is allegedly “A Negro Sermon” about the coming of Christ. The lyrics imitate southern black dialect and contain phrases like “All who don wanter get lef’ in de lurch, Had bedder cum up now an’ jine de church…”2 From the song title, to the fact that she calls it a “Negro Spiritual”, to the imitation of black dialect, this song is already racist for so many reasons. First of all, the text was written by Teresa Strickland. Teresa Strickland was Lily Strickland’s mother, but it was also lily Strickland’s middle name. Therefore, I’m unsure as to which of the women wrote the text. Regardless, it was written by a white woman, and therefore the language is an unacceptable form of appropriation by today’s standards, and also a blatant falsehood to call it a sermon written by a black person.

Lastly, what frustrated me as I did my research was the lack of critical lens applied by scholars to Strickland’s work. I saw books and scholarly articles that all celebrated her pieces, books, and artwork, but nothing that took a deeper glance into the racism she partook in and the implication of performing her works, and especially the spiritual I discussed.

1Walker, Melissa. “Strickland, Lily.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies, November 18, 2016. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/strickland-lily/.

2Walker, Melissa. “Strickland, Lily.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies, November 18, 2016. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/strickland-lily/.