As we enter into this section of our class and begin to grapple with the complexities of Native American song collection, I really wanted to avoid talking about and uplifting white voices. However, I woke up in a “I hate Frances Densmore” mood, and decided that a bit of nuance and background might be necessary to really understand what she was trying to accomplish with her work. Furthermore, Densmore can be compared to a broader trend, the trend of white women “fighting” for Native rights.

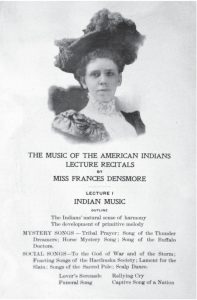

Frances Densmore devoted 50 years of her life to the study of Native American culture and music. When asked “why,” she responded;

“‘I heard an Indian drum.’ Densmore would then relate the story of how as a young girl she often fell asleep to the distant sound of the drumming of her Dakota neighbors on an island near her hometown of Red Wing, Minnesota. These sounds, she contended, somehow became a part of her, constantly calling her back home and reminding her of some larger work to do.” 1

Densmore studied music from a young age, and continued her education at Oberlin Conservatory from 1884 to 1887. In her studies, she came across the work of Alice Fletcher, an anthropologist who worked significantly with Native Americans in the Great Plains area. In working with Fletcher, Densmore sought to distinguish herself from the “feminine disciplines” of humanitarian work and philanthropy, including that of the “Women’s National Indian Association.” However, the distinction was merely in name alone. Densmore’s morals and those of the Women’s National Indian Association aligned on more than one front.

The Women’s National Indian Association encouraged governmental assimilationist programs and did missionary work within native communities under the guise of sentimentality, feminism, and Christianity. Their main drive was to replace the governmental goal of annihilation with assimilation. These women “grasped a colonialist mission with a Kipling-like compulsion they dubbed the ‘white woman’s burden.’”

As defined to its missionaries the work of the Association, among Indians is to teach these to make and properly keep comfortable homes… to teach them the English language; and above all and constantly, to teach them the truths of the Gospel, and to seek their conversion to genuine and practical Christianity. 2

Despite her urgent and intense urge to avoid association with groups such as these, Densmore’s philosophies aligned well with these.

In one letter, she went so far as to argue her preference for separating children from their mothers, contending that “to see her child grow up a lazy, shiftless, ignorant Indian would ultimately cause the dark skinned mother more pain than to part with the child.” She concluded (in culturally insensitive language commonly used by reformers to justify their assimilationist policies toward Native people) that even former Indian “warriors” now demanded “We wantum edjcate.” 3

Behind all of her work lies this philosophy. This philosophy drove her, not the sentimentality of “hearing an Indian drum.” Her ultimate goal and understanding of Native American “issues” were directly tied to an inherent and deep rooted feeling of white supremacy. As we continue our research, we have to keep these philosophies in mind. We can recognize the worth of her work, but we need to be cognizant of the fact that undeniably, Densmore subscribed to harmful supremacist views, and as we continue to do research, we at least attempt to do better and rectify her errors.

FOOTNOTES

1 Patterson, 29.

2 “Missionary Work of the Women’s National Indian Association.” 1

3 Mathes, ix.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Mathes, Valerie Sherer. Women’s National Indian Association: A History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2015.

“Missionary Work of the Women’s National Indian Association.” Philadelphia: November 17th, 1885.