CW: Images of blackface

Prior to the 1840s, performers of minstrelsy were depicted on sheet music and other performance advertisements in costume, with props, and simulating stereotypical aspects of African American life. The images featured white performers in blackface, and often in “dance-like” positions, emulating a dancing enslaved person.

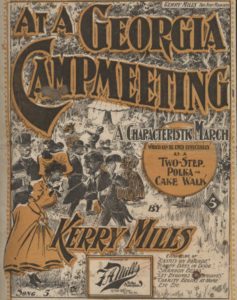

In this representation, the performers are not depicted as someone giving a performance, but rather a “character”, which gives the impression that the performance is realistic and representative of the lives of enslaved people. This can be seen in an advertisement for a performance by Mr. T.D. Rice, a.k.a “The Original Jim Crow”. It can also be seen on the sheet music cover for “At a Georgia Campmeeting”.

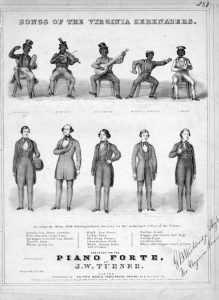

During and slightly after the 1840s, performers began to make their race and identity as a white minstrel performer more apparent and obvious. This was partially because of instances in which minstrel performers were attacked or shouted at by audiences believing they were actually Black and African American performers. Minstrel performers therefore began presenting themselves as respectable, middle class, white performers on sheet music and advertisements.

As seen in this advertisement, the performers are clearly distinguishing themselves from the act of performing, as they are presented both dressed as their “characters” in blackface and then once again in their normal attire (Fig. 3).

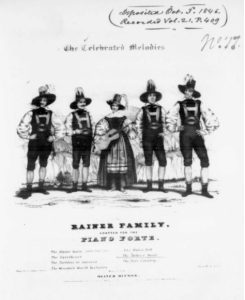

Another reason for the change in presentation came with the arrival of European minstrel troupes, which were often made up of family members. One such family, known as the Tyrolese Minstrels, were known for their stance in which they were arranged in a straight line with their hands on their hips.

This stance made the divide between performer and performance much more clear, as the forward stance alluded to the existence of an audience for the performers.

You’ll notice in this picture that the performers are not in blackface. Some well-known European minstrel troupes didn’t use blackface in the visual sense, but instead opted for an aural blackface in their style of singing and appropriation of the music they sang.

In further research, one might compare this depiction of African Americans and Black people to that of jazz musicians in the 1900s, as minstrelsy and jazz are both regarded as “purely American” art forms that have their own complex relationships with race and racism in America.

It is also worth noting that minstrelsy and minstrel sheet music occurred in two different spaces and reflected the economic class it appealed to at the time. Minstrelsy was originally for the working-class, and the space it was performed in, public halls, reflected that. However, around the time that minstrel performers began to distance themselves from the act of performing, minstrelsy became more popular in more “domestic” middle-class settings.

Sources:

Dunson, S. “The Minstrel in the Parlor: Nineteenth-Century Sheet Music and the Domestication of Blackface Minstrelsy.” American transcendental quarterly (Hartford, Conn.) 16.4 (2002): 241–256. Print.

Foster, Daniel H. “Sheet Music Iconography and Music in the History of Transatlantic Minstrelsy.” Modern language quarterly (Seattle) 70.1 (2009): 147–161. Web.

Sheet Music Consortium