Samuel Floyd Jr. and Rae Linda Brown both allude to the tight community of black composers during the Harlem Renaissance, but I did not process the significance of this until I read some of W.C. Handy’s letters to William Grant Still. Even reading just a few of these letters gave me a much better idea of the relationship between Still and Handy.

Brown notes that Still worked for Pace & Handy’s publishing company first in Memphis and then in New York, acknowledging that:

“Handy’s office was to become important in Still’s career. It was here that prominent black musicians met and made personal contacts so critical to their professional survival.”(72)

Letters between Handy and Still prove an intimately personal in addition to professional relationship. This relationship is most obvious in the non-musical discourse between the two, particularly the familiarity of their greetings and discussions. Handy’s salutations most commonly read “Dear Friend Still,” and he routinely closes with a greeting from his wife or an update on the health of his two daughters, Katherine and Lucille.

Letters between Handy and Still prove an intimately personal in addition to professional relationship. This relationship is most obvious in the non-musical discourse between the two, particularly the familiarity of their greetings and discussions. Handy’s salutations most commonly read “Dear Friend Still,” and he routinely closes with a greeting from his wife or an update on the health of his two daughters, Katherine and Lucille.

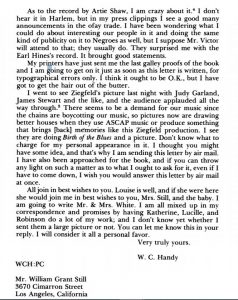

My personal favorite letter dates from April 29, 1941. I am particularly drawn to it because of the synthesis of personal endearment and professional collaboration.

From the first section of the letter it is clear that Handy has sent Still a “script” for his scrapbook. Although the exact context is unclear, my interpretation is that this was a speech of Handy’s. Here, the professional is closely intertwined with the personal; the speech itself was most likely professional in its content, but the familiar tone of the letter suggests that it was sent to his friend simply for Still’s enjoyment. The paragraph closes with a promise to make a new disc so that Still’s son Duncan will have a recording of Handy’s voice.

From the first section of the letter it is clear that Handy has sent Still a “script” for his scrapbook. Although the exact context is unclear, my interpretation is that this was a speech of Handy’s. Here, the professional is closely intertwined with the personal; the speech itself was most likely professional in its content, but the familiar tone of the letter suggests that it was sent to his friend simply for Still’s enjoyment. The paragraph closes with a promise to make a new disc so that Still’s son Duncan will have a recording of Handy’s voice.

In addition to a discussion of sponsorship, new recordings, and the recent Ziegfeld picture, it is clear that Handy’s primary reason for writing this letter was to ask for advice on what he should charge for an appearance in Birth of the Blues as well as for a book. This simple request demonstrates the familiarity with which Handy is able to ask for Still’s opinion and shows that their close relationship is still rooted in their professional lives.

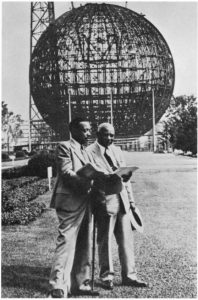

W.C. Handy and William Grant Still, 1939-40.

The letters of this collection are important to see how personal relationships worked alongside the professional musical output of this period. Based on this (albeit limited) evidence, I think Brown’s statement can be amended to include the importance of personal contacts to their social as well as professional survival.

Works Cited

Brown, Rae Linda. “William Grant Still, Florence Price, and William Dawson: Echoes of the Harlem renaissance.” Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance: A Collection of Essays. Ed. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr.. New York: Greenwood Press, 1990. 71-86.

Handy, W.C. and Eileen Southern. “Letters from W.C. Handy to William Grant Still.” The Black Perspective in Music , no. 2 (1979):199-234. Accessed October 26, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1214322.