Helen Walker-Hill’s 2002 book From Spirituals to Symphonies: African American Women Composers and Their Music chronicles the lives of eight black female composers. This resource 1

not only provides detailed biographical research and quotes from these eight figures, but contextualizes each composer within the historical space in which they worked. Undine Smith Moore is one such composer whose career and academic legacy provides a crucial perspective about the unique challenges and strengths that accompany the way we interpret her work.

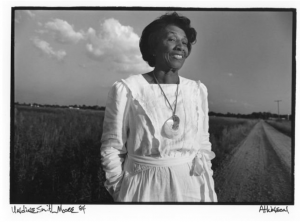

I first heard of Undine Smith Moore when I performed her choral piece We Shall Walk in the Valley of Peace at St. Olaf. That striking melody has stayed with me ever since I learned it, but I never encountered any of her work outside of performance. Moore lived from 1904-1989 and attended college at Fisk University from 1924-1926 where she received the first scholarship from Julliard for her studies. Post-graduation, Moore worked in North Carolina and Virginia before pursuing her Master’s degree at Columbia University. The artistic arc of Moore’s life was shaped around academic institutions, and the powerful mentorships that follow. However, Moore also addresses a prevailing sentiment she encountered as a composer, writing:

“There is in addition the fiction of women’s inability to deal with the abstract. Because music is an utterly non-verbal art, there is inevitability a certain quality of the abstract in the approach to the composer’s art. Women, for a long time in the past, were indoctrinated with the widely held belief that the abstract is not their sphere…Over and over, it has been held that the objective discipline which is necessary to transmute inner sources by giving them artistic form is a discipline suitable only to men”

Moore expresses a very specific frustration in this quote, arguing that the reproduction of existing music may be acceptable for women, but that the act of composition is tied to an internal understanding of something abstract. Legacy and respect, therefore are earned through creation as opposed to the borders of excellence that women were expected to stay within. Undine Smith Moore echoes this point when discussing power dynamics in black churches

“Women could and did influence the building of a school, the choice of teachers, and the order and content of the church service, but there must have been a subtle etiquette that kept them in a particular place. Further, so far as I know, the influence of women on the music and the culture in the life of the Black community, while known and applauded, was rarely, if ever, documented.”

If Undine Smith Moore is correct in her assertion that as a musical culture we value the things that we document, how can recent efforts to re-examine these “lost” histories of music makers do that in a way that doesn’t reinforce a hierarchy of “abstract” musicking as legitimate and all others as less thoughtful, less truthful, and ultimately less powerful.

1Walker-Hill, Helen. From Spirituals to Symphonies : African-American Women Composers and Their Music Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 2002.